Story by Jillian Laurel Steinberger, with photos by Liz Birnbaum

We drive up the windy country road on an early fall afternoon in Bonny Doon near Santa Cruz, to see what Kori Hargreaves is doing with hyper-local fibers and dyes. The light filters through the leaves of tall redwoods and oaks, and we emerge at a clearing, where Kori is processing indigo on the deck outside her yurt. Her hands are blue, and her clippers stick out of the side pocket of her Carhartts, at the ready.

My friend Liz and I get out of the car, stretch and lay our eyes on Kori’s garden. It is beautiful and useful, humming with life. I like this garden. Many of the plants will be harvested for natural dyes. And when she harvests them she’ll save the seeds, which she packages and sells online at Ecotone Threads.

There are cosmos and marigolds and California fuschia. And woad, and weld. Several different monkeyflowers. There is also goldenrod, orange bidens, coreopsis, and madder root. Many plants are also edible, or medicinal. Kori also harvests the surrounding native plants for dyes: mugwort, artemisia, oak bark, oak galls… And the bees are buzzin’.

With a B.A. in plant biology and studio arts from UC Davis, Kori is a second generation agroecologist and artisan. Both of her parents are ceramicists, and Kori works with her mother, Maia Farrell, co-managing the vegetable, herb and cut flower gardens at a nearby coastal ranch on Highway 1—where she also has more dye plants. Her dad, John Farrell, taught at the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, a few miles away. It was founded by the iconic, visionary gardener, Alan Chadwick, at UC Santa Cruz. People from all over the world come here to learn how to farm—and garden—artfully. This is where Kori was born.

Freestyle Weaving & Intentional Mistakes: The Saori Loom

Kori is making a top to go with the jeans at Grow Your Jeans—it’s one of the looks that will be featured on the runway. She’s weaving it on her beloved Saori loom, which has a great back story. Well, a couple.

Kori bought her Saori loom several months before her wedding, intending to weave her wedding dress (below left) on it, which she did. She wore the dress when she married Toby Hargreaves in Fall of 2014. In fact, she and Toby saved up the money together to buy it. Very sweet. So that’s one good story.

The other has a cosmic ripple effect. The Saori loom was developed about 40 years ago in Japan by a woman named Misao Jo, who is now 102 years old and still weaving every day. Kori recounts that Misao Jo started out weaving obis (a sash worn with traditional Japanese dress) for kimono, a traditional and rigid art form in Japan. She decided to break out of the box by making intentional mistakes. It made an impact.

“Misao Jo started this incredible revolution in weaving that is all about finding yourself through your art form, and finding beauty in mistakes, and having the freedom to express yourself in the moment and not worry about the product, but be fully immersed in the process. And that resonates very strongly with me, so when I found that in weaving it clicked.”

Misao developed Saori weaving with the help of her son Kenzo, who has designed and built the Saori looms from the beginning. The Saori loom is one of the few looms where you can have several projects going at once, with the same loom. In other words, you don’t have to end your project by cutting it off. If you want a break from it, you can take it off and start something new, then put it back on later. Kori also praises the exquisitely crafted tools that come with the loom.

When she shows me her loom she points out what’s on it: Sally Fox’s cotton is on the warp, and wool from Sandra Charleton’s Sheepie Dreams Organics, a small family farm in Santa Cruz, is on the weft. Kori handspun the yarn herself from wool from Sandra’s Romney and Wensleydale sheep. “They produce a medium coarse wool but Sandra’s are exceptionally fine in my opinion. It’s fun to spin, it’s a crisp fiber.”

All this is what went into her top for Grow Your Jeans.

She has a great look, but Kori’s style is more earth mama than fashionista. “Fashion in my book is less about current trends and more about feeling good in my skin,” she explains. “I rejoice in creating textiles that are so clearly made by hand that people can’t help but see them and wonder about the stories they hold! I want to bring back a feeling of preciousness to our belongings, rooted in an inherent understanding of the work and skill that is required to make them.”

Home-Scale Indigo

Kori points to what looks like a painter’s tray on the deck of her yurt. “This looks like pond scum but it’s actually indigo pigment.”

The traditional Japanese way of processing indigo requires composting the plants on a specially constructed floor, the way the Fibershed Indigo Project does it. Kori estimates you need to harvest around 5,000 plants, or 450 pounds of dried leaves, to create the necessary hot compost pile. She doesn’t have that much growing space, and she doesn’t need that scale.

So Kori uses a method that is more common in Southeast Asia and Central and South America. Instead of composting the plants, she ferments them in a water bath, and essentially distills the pigment out of the leaf matter, and then dries it into a powder. “When people buy indigo pigment from El Salvador, that’s what they’re getting. It’s the same thing as what I’m making.” (Instructions in Kori’s blog.)

To my eyes, the pigment powder is so incredibly gorgeous that it’s uplifting. Just looking at it, I feel elated. It’s clearly a special medicinal potion. Maybe it has a positive health impact when you wear it?

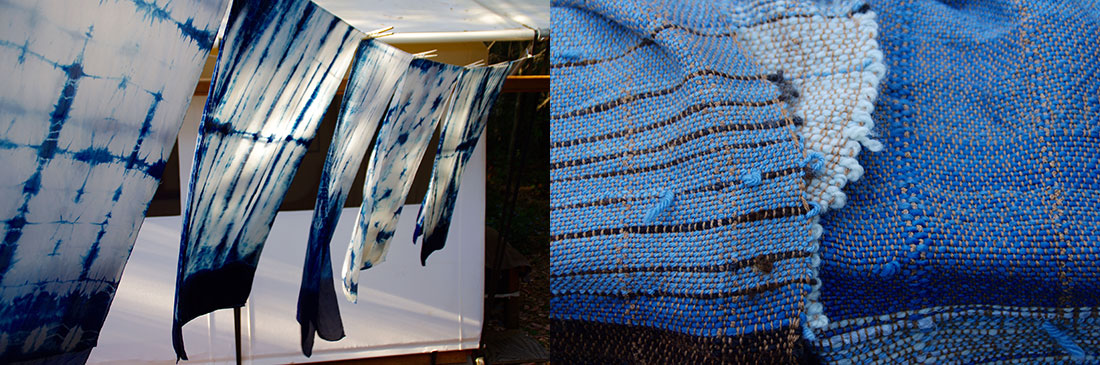

Anyway, Kori calculates that it takes about three to five ounces of indigo pigment to make a concentrated vat, in which you can make several scarves. Recently she harvested six large, healthy plants, which resulted in about nine ounces of pigment after processing. Mostly, she uses it and her other natural pigments to color wool yarns for her weavings and shibori scarves.

Incidentally, a garden design point: indigo makes a lovely summer hedge, before it is chopped down for the winter and harvested! Who knew indigo was a hedge plant.

Children as Flowers: Hmong Batik

The Hmong, a tribal people of Vietnam and Laos, practice a special kind of batik with their indigo pigment. Kori has been gleaning whatever information she can, and she will soon travel to study with them. She shows us a splendid scarf that she made in this style. She wove it from Sally Fox’s pima cotton on her Saori loom, and dyed with indigo from her garden. Beeswax from her top bar hive was used in the batik process.

Batik is drawing or painting with hot beeswax. The tools used in batik are called tjanting tools, and are essentially pens made to hold hot wax. This is used to draw motifs and patterns on white fabric. The fabric is then dyed blue with indigo. The waxed areas resist the dye, so when the wax is removed what is left is a blue fabric with white motifs.

“It took ten dips in the vat to get that deep indigo color,” she says.

Kori explains that the Hmong people didn’t have a written language, but they communicated with symbols on fabric. Many of their symbols are agricultural. As an example, she has painted designs from rice seeds with cucumber blossoms and pumpkin seeds on her scarf. “Depending upon how the women combine these patterns and symbols, they communicate different things. They make special carriers and wraps for their babies covered in flower motifs, and they believe that if you disguise your child as a flower then evil spirits won’t steal them away. The evil spirits won’t see them—they’ll think they’re flowers.”

Some Parting Thoughts

What does Kori love about Fibershed? She loves the personal connections she has made, and she’s especially thrilled that she received a scholarship to take Sally Fox’s workshop, Cotton Breeding Part 1: Cross Pollinating Flowers. Sally has been a huge inspiration. In fact, cotton flowers from Sally’s seeds are blooming in her garden—but she has not tried to dye with them!

She also loves Fibershed’s advocacy and research. She appreciates how Fibershed has developed awareness of problems in the textile industry. “I enjoy the articles they’ve posted about the Kentucky and Colorado hemp projects. I’m really excited about hemp, and I love that they’re doing such a great job of documenting their research.”

And a parting meditation on art: “When we openly put care and attention into the work we do, beautiful things can be created, and we can’t help but learn along the way!” says Kori. “For me, the real treasures lie in the process itself, not the end result. Ultimately the finished work is a tactile expression of my personal adventures, filled with love and gratitude, questions, resolutions, community connections, and hope for the future.”

After an enchanting afternoon with many “oohs” and “aahs” at plants, seeds and special powders and pigments, as well as lovely woven things, we say our goodbyes and drive back down the hill toward Santa Cruz…

You can see the work of Kori Hargreaves and 55 other regional farmers, ranchers and designers whose fiber and artistry will be available for purchase, and featured in the fashion show at Grow Your Jeans, on October 3, 2015, at Mann Family Farm in Bolinas, California. Tickets on sale here.

Jillian Laurel Steinberger has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Bay Area News Group papers, BUST, Bitch, Edible East Bay, Edible Monterey Bay, and other publications. As a landscape designer, she loves creating inspiring spaces with a focus on native plants and edibles for year-round color, food, and pollination. jillian@garden-artisan.com