Dyeing with mushrooms is a relatively new practice that gained popularity in the 1970s, thanks to the experimentation and publications of Miriam C. Rice and Dorothy Beebee. Their work laid a strong platform for continuing research and advancement. There is no better time than now to pay closer attention to the resources available to us in the means of local, renewable dye sources, as we work to build a healthier planet and support our local ecosystems.

Mushroom dyes have a lot to offer in the way of color and availability. They come up when the fungal organism is ready and offer themselves to our basket; much like ripe fruit from the garden. Here’s a look at sustainable ways to work with these valuable pigments and incorporate them into our regional dye palette.

For those who are just getting started with the dye process, here are some general instructions for using mushroom dyes.

- Start with roughly the same volume of freshly collected fungus to fiber, or if working with dried mushrooms start with equivalent weight of fungus to fiber.

- Break mushrooms into small pieces and simmer them in water for about an hour. The amount of water you add to the mushrooms will not dilute your dye, so if you need to top it off after extracting, go ahead. You may choose to strain the mushrooms from the dye pot, or leave them in. The pieces usually wash out of yarn pretty easily.

- Simmer your fiber in the dye bath for an hour, (aim for 180F for most species), and then cool. If color is pale, let cool in dye pot overnight, but if dye is strong you can use it a second time for interesting results. When dye process is complete, rinse and wash the unbound dye from the fiber and let air dry.

The depth of the colors you achieve are influenced by five crucial elements in this process: the type of fiber, mordants, pH modifiers, the temperature of the dye bath, and the type, amount and condition of mushrooms used.

The Fiber

Mushroom dyes, like many natural dyes, work best on protein fibers like wool, alpaca and silk. Cellulose fibers like cotton and linen require additional treatments to retain the dye pigment. Some mushroom dyes work best without additives, but many colors are greatly enhanced by adding mineral salts, called mordants, to the fibers.

The Mordants

Commercially-available mordants usually come in a powdered form. Generally, alum (aluminum sulfate) is used to brighten colors and iron (ferrous sulfate) is used to darken them. The mordant powder is dissolved in water and simmered for an hour with the wool to be dyed, before the dyeing process. There are additional mineral based mordants that have fallen out of favor due to their potential toxicity, but alum and iron are considered safe.

Alternatives to Commercial Mordants

There is a movement to replace commercial mordants with locally-sourced alternatives. Plant sources that are frequently used include oak galls for their tannins and rhubarb leaves for their oxalic acid. Less common sources include club moss, which is a rare and protected plant, and Symplocos, which proves difficult to grow. However, while researching alum, I came across mention of a raw mineral called alunogen, which has been collected from several sites in Northern California. Alunogen is a hydrated form of alum, and appears to be a good candidate for further experimentation; a mineral club may provide helpful insight on further studies.

pH Modification

Dye colors can also be enhanced by shifting the pH of the dye bath. The most commonly used pH modifiers are either ammonia or washing soda for an alkaline shift, and vinegar for an acidic shift. An easy-to-make, locally-sourced alkalinizing agent is ash water; simply add a half-cup of wood ashes to a cup of water in a quart size jar, shake, and let stand for a few days. Add small amounts of ash liquid to the dye bath to raise the pH to 9. Be sure to wear gloves when working with this liquid, because the high pH may cause burns if left on skin. Lemon juice, vinegar or other acidic substances can be added to certain dyes to brighten the color; for an acidic dye bath, aim for a pH 4.

The Temperature

The temperature and amount of time the fiber is simmered in the dye bath is crucial for achieving optimal color results. There are many different types of pigments found in fungi, some of which are sensitive to excessive heat. In a matter of seconds you can see beautiful violet turn to beige in several different dyes. For most dyes however, keeping the dye bath between 165F-180F and simmering the fiber for an hour will produce the best results.

The Mushrooms

Northern California has a wealth of wild mushrooms that contain a full spectrum of bright, permanent dyes. Most of the mushrooms used for dyes fruit through fall and winter, when cooler weather and rain come to the region. Mushrooms are the fruiting structures of a larger organism; unlike plants and lichens, the organism is not destroyed or harmed by collection, which means they can be sustainably harvested, if done mindfully, for small batches of dye and individual projects.

Many dye mushrooms have complex relationships with trees and shrubs or other organisms. These relationships are not fully understood and are not easily reproduced in the lab or garden. Some dye mushrooms are wood decayers and therefore could potentially be cultivated, but the commercial demand is not high enough for this to be a lucrative endeavor. For these reasons, dye mushrooms must be collected in the wild.

Dye mushroom habitats are varied, and in Northern California they include urban landscapes, oak-filled canyons, coastal pine bluffs and fog-laced spruce groves. Mushrooms require moisture to fruit, but often all that is needed is a little hydration from a light drizzle, irrigation systems or fog drip. A decaying stump will hold moisture like a sponge, and in a dry fall or winter season may be the best place to look for dye mushrooms.

The following are a selection of Northern California dye mushrooms that are capable of producing bold colors using entirely locally-sourced ingredients. Some of these mushrooms give their best colors with a pH shift, and others work best with mordants, but all can be used either fresh or dried with just water and homemade pH modifiers for beautiful results.

Hypomyces lactifluorum, the Lobster Mushroom. Although not terribly common in Sonoma County, it is frequently found in Mendocino County and is more common as you head north along the coast. It is found in Douglas-fir, Sitka spruce and hemlock forest in the fall, and is easy to recognize by its malformed shape, orange to red-orange color, and lack of gills under its cap. It is considered to be a gourmet mushroom by many, but it is often found past its prime — perfect for the dye pot. This mushroom gives its best color when fresh, but can be stored for later use by freezing it, or drying out all the moisture, and storing it in air tight jars or plastic bags. Lobster mushrooms give a Tang-orange color with no mordant in neutral pH dye bath, while alkalinizing the dye bath with a little ash water will shift the dye color to hot pink or magenta.

Cortinarius smithii is a strikingly beautiful mushroom commonly called the Red-capped Cort. It is a slender mushroom that has a reddish cap with dark burgundy-red gills and a yellow stem. It can be found in coastal pine forests from late fall into early spring. This is a small but powerful dye mushroom, which is sought after by dyers for its ability to make beautiful red, orange and violet dyes. To enhance the reds, it is best used with an alum mordant. An iron-rich or high-pH dye bath will shift the colors towards the violet-purple realm. If extracted in just simmering water it makes a beautiful dusky rose dye, but adding a splash of vinegar to lower the pH will result in a bright orange dye. The name is listed as Cortinarius phoeniceus var. occidentalis in most books, but it was recently determined that our Red-Capped Cort is a distinct species and has been given a new name.

Cortinarius cinnamomeus, commonly called the Orange-gilled Cort, is another excellent dye mushroom. Like the Red-Capped Cort, it is commonly found in coastal pine forests throughout the winter. It looks rather dull from the top, but when you flip it over, the underside is lit up with flaming orange gills. This mushroom will give you pale pastel peachy-orange colors if extracted in simmering water alone. When you add a little vinegar to the dye bath, the color will intensify and bloom to a very bright orange dye.

Gymnopilus ventricosus, or the Big Gym, as the name implies, is a giant dye mushroom that is hard to miss. It is a very common wood decayer that grows in large clusters at the base of dead or dying pine trees or stumps. You can get beautiful warm butter yellow colors from simply simmering the mushroom with wool. This mushroom works best fresh, or saved for later use by freezing it, as it tends to lose some of its potency if dried.

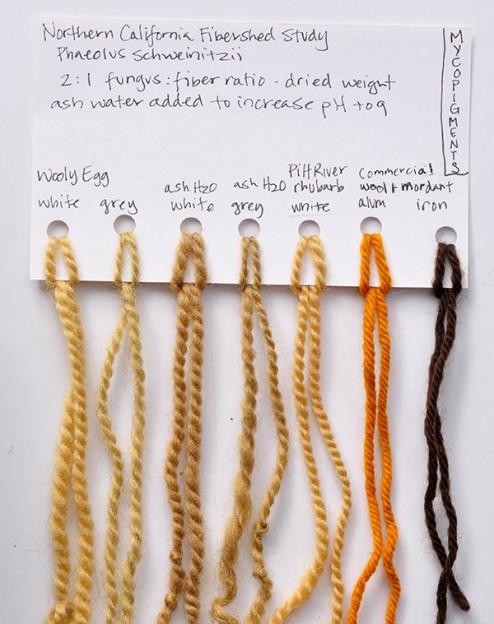

Probably the most abundant dye mushroom around is Phaeolus schweinitzii, which is commonly called the Dyer’s Polypore. It is a pathogen and decomposer of conifers, often found at the base of mature trees and stumps throughout the fall. It can grow quite large in size; fruiting bodies over a foot across can be found in wetter seasons. Unlike most other dye fungi, this fungus is best collected while it is still in the early stages of growth. The young, golden-velvet buds sometimes give a brilliant yellow color with no mordant at all, a bright golden yellow can be achieved with an alum mordant and at all stages you may use an iron-rich solution to target the sage to olive green pigments. The yellows become weaker and dingier as the mushroom ages, but the iron enriched green pigments will persist.

Pisolithus arhizus, the Dyer’s Puffball, is one of the strongest dye fungi known. Although it grows in relation to pines and oaks, it is most often found in high traffic areas such as trail sides and medians. Hunting for the Dyer’s Puffball can be done while doing other activities like riding your bike or walking the dog, as they are easy to spot from a distance by their odd shape and brown spore deposit that spills onto the surrounding ground. Be sure to carry bags for collecting this mushroom because the powdery spore mass can be very messy to handle. The dye is so strong it will stain your hands, clothes and pretty much anything it touches; it is one of the few mushroom dyes that will stain counter tops. This fungus gives a wide range of warm colors from deep yellow to autumn gold to dark cocoa brown. The color variation of the dye is greatly influenced by the age of the fungus, the pH of the dye bath and the addition of minerals to the dye water.

Omphalotus olivascens, the Western Jack O’Lantern, is a California specialty. This mushroom thrives in coastal oak forest and is coveted by dyers all over the world. It is called the Jack O’Lantern because when fresh it will actually glow in the dark. It starts growing in the fall, soon after the first heavy rains, but will continue fruiting well into winter, in most years. Look for it clustered at the base of dead and dying oaks. It is capable of producing a dark violet dye without any mordant. However, dye bath temperature seems to play a role in color optimization; aim to keep temperature at 165F and remove wool from dye bath when color looks good. A dark forest green color is easy to achieve with an iron rich dye bath.

Resources

Joining a mushroom club and talking to knowledgeable members is the best way to learn about mushrooms. The Sonoma County Mycological Association called SOMA for short, has several experienced mushroom dyers and is a great regional resource for learning more about fungi. There’s also the Mycological Society of San Francisco (MSSF), and the Bay Area Mycological Society (BAMS).

Alissa Allen has been experimenting with mushroom derived pigments for 15 years. Raised by a forager in the Pacific Northwest, she has been a student of the natural world her entire life. For the past two years she has been travelling around the US; studying regional habitats and sharing local mushroom dye palettes with fungophiles and fiber artists alike. Mushroom identification is her primary passion, but Mycopigments are her obsession. In addition using mushrooms for dyes, she is currently exploring lichen dyes and mushroom pigments for paint. You can read more about mushroom and lichen dyes and her workshop on her website, or follow Mycopigments on Facebook.

Alissa will be teaching a mushroom dye class sponsored by Fibershed on January 26, 2014 in Napa. More information here.