Written by Veronica Kassatly

( This is just a quick primer. Anyone looking for more in depth analysis will find it in “The Great Green Washing Machine Part 1:Back to the Roots of Sustainability.”)

Defining Sustainability: Back to the Roots

In fashion, sustainability appears to have become an elitist, even imperialistic concept in which the interests of the global north define the conversation. These interests are both those of the present generation, whose right to purchase and discard clothing in volume the system seeks to preserve (by switching to ‘circularity’ and ‘more sustainable’ fibers), and the interests of future generations whose needs are to be secured at the sacrifice of producers whose fibers do not meet the global north’s unilaterally declared ‘sustainability’ standards.

As part of this narrative, sustainability is equated with environmental impact. But “The environment does not exist as a sphere separate from human actions, ambitions, and needs…the “environment” is where we all live; and “development” is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable” (pg. 7)

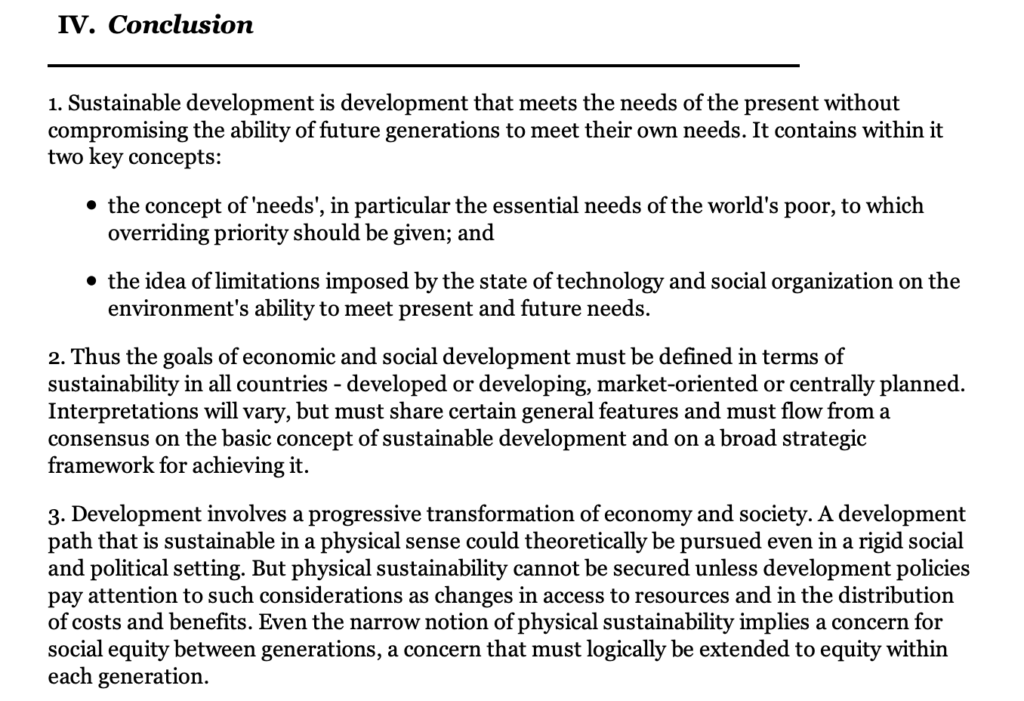

This is a vital notion, highlighting that sustainability encompasses environmental and socioeconomic dimensions because they are inextricably linked. That quote comes from the 1987 report to the United Nations by the Brundtland Commission, which is the foundation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As the Brundtland report also observes: “Even the narrow notion of physical sustainability implies a concern for social equity between generations, a concern that must logically be extended to equity within each generation” (pg. 41). It automatically follows that in aiming to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, overriding priority must be given to meeting the essential needs of the world’s poor. Brundtland also notes that this is to be achieved considering what is technologically possible, and who has access to that technology.

Here, it is vital to remember that since the Brundtland definition underpins the SDGs, if any corporation, initiative, or sourcing site tells you that they are adhering to those 17 sustainability goals, they are claiming to adhere to the Brundtland definition of sustainability.

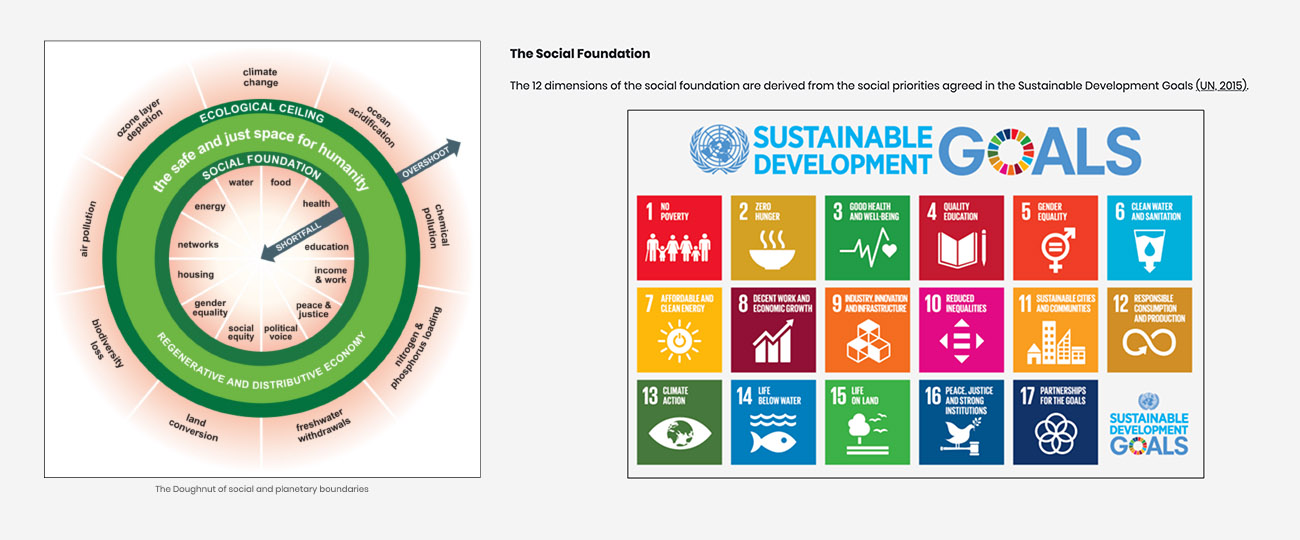

Since exactly what this means is vital, perhaps an easier way to envisage what Brundtland is talking about is Kate Raworth’s concept of Doughnut Economics. “A compass for human prosperity in the 21st century…it consists of two concentric rings: A social foundation – to ensure that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials. An ecological ceiling – to ensure that humanity does not collectively overshoot planetary boundaries. Between these two boundaries lies a doughnut-shaped space that is both ecologically safe and socially just.”

As Raworth points out “meeting the needs of all within the means of the living planet…must be done from both sides at the same time.”

And, as shown, the Doughnut’s social foundation – below which lies critical human deprivation – derives its 12 dimensions from the SDGs.

As I illustrate here, token references to the SDGs notwithstanding, that globally agreed definition is not currently applied in sustainable fashion, with potentially profound adverse consequences for both planet and people.

Methodology and Evidence Matter

The Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) – a members club of the biggest money in fashion – was founded by Walmart and Patagonia. It is best known as the creator of the Higg Index “a core set of five tools that together assess the social and environmental performance of the value chain and the environmental impacts of products.” One of those five tools is the Materials Sustainability Index (MSI). It’s the only tool that is not behind a paywall, and the MSI is the index most commonly used by fashion’s largest and richest companies to measure the global impact of their fiber and fabric choices – including Nike (US$37.4 billion), H&M Group (US$24.8 billion), and Inditex (US$20.4 billion).

The MSI purports to measure the ‘sustainability’ per kilo of different fabrics, across 5 different variables: Global Warming Potential (GWP), water scarcity, eutrophication, chemistry, and fossil fuel depletion. Despite the SAC’s claim to “assess social performance,” there is no socioeconomic variable in the MSI. So a fiber’s impact in meeting the needs of the world’s poor is categorically, not considered.

This means that the MSI is not a sustainability index. It’s an environmental impact index.

This is particularly important for farmed fibers like cotton, silk, or wool, as so many disadvantaged communities, particularly in the global south, depend on these as a cash crop and source of export income.

Take sub-saharan Africa. It is one of the most disadvantaged regions in the world. In Benin, Burkina Faso, and Mali, for example, Some 40-50% of the population lives below the poverty line; 70%-80% of their employment is in agriculture; and cotton is the principal cash crop. Indeed, cotton generates 50% of Benin’s foreign exchange, almost covering the total cost of Benin’s most important import by value – rice.

Using Brundtland as a framework, we can see that buying sub-saharan cotton clearly benefits millions of people whose basic needs are categorically not currently being met. As for environmental impact, since the cotton is rain-fed its water scarcity is zero. Whilst International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) data for 2021 shows that the rates of fertilizer application averaged 11kg/ha in Benin, 7kg/ha in Burkina Faso, and 4 kg/ha in Mali (cotton’s global average was 219kg/ha). Similarly, 2018 FAO pesticide data, shows that in Mali, active ingredients per hectare averaged 0; and in Burkina Faso, 0.14 kg/ha (the global average for cotton was 5.7kg/ha). Clearly to suggest that conventional sub- saharan cotton should be avoided on environmental grounds is unsubstantiated nonsense.

If the environmental impact is low, however, the yield is even lower. According to the ICAC, in eleven African countries, cotton fiber yields are less than 400 kg/ha. The average yield in Bangladesh is almost double that (772 kg/ha). And this is where Brundtland’s second caveat comes in. Technological transfer can help farmers increase their yield from the same resources – reducing environmental impact per kilo of fiber and increasing farmer income. Indeed, a new ICAC project plans to double the yields of at least 50,000 smallholder cotton farmers in Zambia by January 2024.

At the present time, fashion’s leading corporations, however, profess sustainability largely by investing in recycling or alternative fibers. To the extent that they invest in helping the poorest to meet their needs, these behemoths ‘invest’ in cotton – specifically in such identity cottons as organic, BCI, or CmiA . Despite the tens of millions of dollars ‘invested’ in such initiatives, I have been unable to find a single robust, independent, study that demonstrated that they actually benefited the farmers concerned. Indeed, the few studies that I have found, demonstrated the opposite.

There, in a nutshell, is what sustainable or more sustainable does and doesn’t mean. So how many of fashion’s global corporations and initiatives measure sustainability accurately?

As far as I can see, not one of them. Even if we ignore Brundtland, and only consider impact in terms of GWP, water scarcity, eutrophication, etc.,the MSI scores are not accurate. They can’t be, because the requisite data does not exist.

The MSI is based on LCAs – Life Cycle Analysis. But you can only compare LCAs that have been produced using exactly the same boundaries and methodology. There is no standardised suite of LCAs for global fiber production.

To get around this data vacuum, the MSI compares LCAs that use different methodologies and boundaries.

The SAC and its supporters have recently taken to claiming that the MSI is not intended to compare different fibers with each other, that it is only intended to compare “best in class,” and so this failure does not matter. But that is not what the Higg website states, and I quote:

“The Higg MSI is designed to compare the environmental impact of different materials so design and development teams can make more sustainable choices during materials selection.”

Moreover, until January 2021, the MSI offered a Benchmark option. Clicking on this for any given fabric produced a rating. For example, for silk, the MSI stated: “Silk is better than 0.0% of textiles.“

The benchmark has now been deleted, but the MSI implicitly and intrinsically, still compares different fibers. If your index states that according to standardized metrics, silk fabric has an average impact of 1086/kilo, alpaca fabric has an average impact of 320/kilo and polyester fabric, of only 36.2/kilo, you are by definition saying that silk and alpaca are less sustainable than polyester.

Furthermore, as I illustrate here, comparing LCAs that have been produced using different boundaries and methodologies, generates some illogical, unscientific, and unjust outcomes. For example, for organic cotton fabric, manure is put outside the boundary. The environmental impact of the cattle in producing that manure is not included. Which results in very low GWP and eutrophication scores, of 1.28/kilo and 3.96/kilo, respectively – suggesting organic cotton is very sustainable.

For silk, on the other hand, the impact of the cows in producing the manure is included, resulting in a eutrophication score for silk of 589/kilo, and 78.1/kilo for GWP – suggesting silk is very unsustainable.

Silk and organic cotton also have radically different scores for water scarcity. But almost all silk used in global fashion comes from China. According to the International Sericulture Commission (ISC), a UN-affiliated intergovernmental agency created to support the overall development of the silk industry, all Chinese silk is 100% rain-fed, with a water scarcity of zero. So where does the MSI get a silk water scarcity of 348/kilo from?

There is no global generic LCA for silk, so the Higg uses a 2014 LCA, evaluating the practices of 100 farmers in Tamil Nadu, in 2006. These farmers lived in a dry area, had no access to solar power or drip irrigation, and generally employed outdated and wasteful production practices. The MSI scores, however, are extrapolated directly from those practices, and so imply that all silk is produced with 100% irrigation of the most wasteful kind.

As for the MSI water scarcity score for organic cotton, of 4.89/kilo, that was derived from a 2014 LCA that considered almost entirely rain-fed cultivation. But Textile Exchange’s Organic Cotton Market Report 2021, clearly shows that if organic cotton was once mainly rain-fed, it certainly isn’t now. In 2019/20 more than 16% of the global supply was cultivated around the Aral Sea (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), with some of the highest irrigation levels in the world – a water scarcity further inflated by the extraordinary inefficiency of the soviet era irrigation system.

To obtain the astonishingly low purported average impact of 36.2/kilo for polyester, on the other hand, the MSI bases its metrics on an LCA produced by industry group, Plastics Europe. This LCA only covers EU production – which represents a mere 2% of the global total. It is based on 2009 data that is no longer representative even of EU sourcing, and since “impacts of crude oil extraction and refinery can vary by a factor of seven depending on the location(pg. 111),” it clearly grossly underestimates the impact of global polyester production.

The Global Impact of Brand-Driven “Sustainability”

Comparative sustainability claims – assertions that one fiber, process, or system is more sustainable than another – have consequences. Their aim is to persuade brands and consumers not to purchase clothing, fabric, and fibers rated ‘unsustainable’, but to purchase those rated ‘sustainable’ instead. By definition, the producers of ‘unsustainable’ goods are going to lose sales – possibly, go bankrupt. Indeed, entire sectors could be destroyed. To quote Joao Berdu of Brazil’s Vale da Seda: “lots of money is being invested to jeopardize the image of silk and put at risk the income of millions of small farm households that are producing silkworm cocoons in less developed regions in China, India, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Thailand and Brazil.”

Indeed, the world’s two least sustainable fibers, according to the MSI, are in fact silk and alpaca, and the ISC asserts that global annual silk production fell from 202,000 tonnes in 2015, to 91,800 tonnes in 2020. [1] Whilst, Peruvian alpaca exports totalled a ten-year high of US$219 million in 2018, and only US$120 million in 2020. This suggests that comparative assertions do indeed have the impact intended. More egregiously, not only are those who contributed the least to climate change going to suffer the consequences the most, in fashion at least, it is they who are being forced to pay to mitigate its impact. To quote Dileep Kumar of the ISC: “the Higg Index has emerged as a green washing tool for synthetic fiber manufacturers to promote their products. The Higg Index methodology has been created in such a way that some of the major environmental categories that are disadvantageous to synthetic sectors eg. micro-plastic pollution, were completely avoided as impact categories. On the other side, the [beneficial] inherent factors associated with natural fibres in production, use, and disposal were also not counted.”

All of this raises serious ethical concerns. Nobody should be saying that one fiber is more sustainable than another unless they are absolutely certain that they are correct and they have the data to prove it. As I have just demonstrated, the MSI does not have the data to substantiate its claims. So who is checking? The answer is no one.

In 2019, with $11 million in Series A investment from Buckhill Capital LP the “Higg was spun out of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition as a public-benefit company”. Meaning that it is: “a specific type of Delaware General Corporation owned by shareholders…profit is the point – as is returning money to the shareholders.” In addition, as a Delaware public benefit, Higg is required to report its progress toward its benefit purpose only to its shareholders, not to the general public. In short, there is no independent oversight as to whether Higg Co. is indeed working for global benefit rather than for its shareholders’ profits.

Worse, there is neither recourse nor redress in the Higg system. In October 2020, objecting to the MSI’s unsubstantiated vilification of silk, the ISC filed a complaint with the SAC. The SAC refused to alter or remove the silk score, and in a grotesque miscarriage of justice, there was nothing the ISC could do about it. Astoundingly, no brand or initiative would help, and the ISC were forced to turn to the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

On June 16, 2021, the FTC replied to the ISC’s complaint.

“While the FTC is not able to intervene in individual disputes, the information you have provided has been recorded in our secure online database which is used by thousands of civil and criminal law enforcement authorities worldwide. This database enables law enforcement agencies to identify questionable business practices that may lead to investigations and prosecutions. In addition, our attorneys and investigators regularly review the complaint database to look for law enforcement targets, evaluate the need for consumer education, and make policy recommendations. Your letter has been added to our database for that purpose.”

The FTC also advised the ISC to file with the relevant State Attorney General’s Office. I am told that they have done so. The SAC’s response is to dismiss this complaint as a “myth.”

The behemoths of fashion seem happy to play along. As of August 19, 2021, the Cotlook A index [2] stood at US cents 103.35/lb. Equivalent China polyester staple [3] was around US cents 48.27/lb. Any index that says that the cheapest mainstream fiber – polyester – is also the most sustainable is obviously extremely valuable to these behemoths. But as I have illustrated here, it is also extremely damaging to both the environment and to global justice.

Notes

[1] By comparison, 2020 global polyester production totalled 57.1 million tonnes and cotton totalled 24.1 million tonnes.

[2] Average price of a base grade of cotton delivered to East Asian ports, collected by Cotlook Ltd, a private company in Liverpool

[3] Average price of polyester staple of a denier that competes with cotton delivered to Chinese mills in the East, collected by the China Cotton Association.