Fiber Visions: Dogbane

What would it look like to honor the principles that underlie Indigenous stewardship and use of dogbane in all the relationships that meet our material needs? How could this shape gardens, farms, and landscapes?

“We desperately need to foster a new vision of human-nature relationships and the place of humans in the natural world. Those who peopled California before the arrival of Westerners are some of the best teachers.” –Kat Anderson

The knowledge expressed in these graphics was developed by generations of Indigenous people and shared by Redbird (Pomo/Paiute/Walaiki/Wintu), Nick Tipon and Dr. Peter Nelson (Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria), Ben Cunningham-Summerfield (Mountain Maidu/Pit River/Anishinaabe), and others. We show one possible annual cycle developed and shared by members of the Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok people. It is appropriate to their traditional lands in Northern California, and it illustrates key principles that may guide practices for differing peoples and places. We also draw upon the thinking of European American author Kat Anderson, who worked closely with California Indigenous peoples to write the book “Tending the Wild.”

For more information, read the First Nations Development Institute’s report “Recognition and Support of Indigenous California Land Stewards, Practitioners of Kincentric Ecology.”

Dogbane needs to be gathered and propagated with permission and care, and harvesting from wild plants and propagating new ones should be done in conversation with local Indigenous people and land stewards. For example, propagating dogbane with stocks from outside a tribal group’s ancestral homeland may not be appropriate. One great way to get involved is to volunteer. For example, the Dogbane Preserve in Santa Rosa hosts annual volunteer days to tend the land.

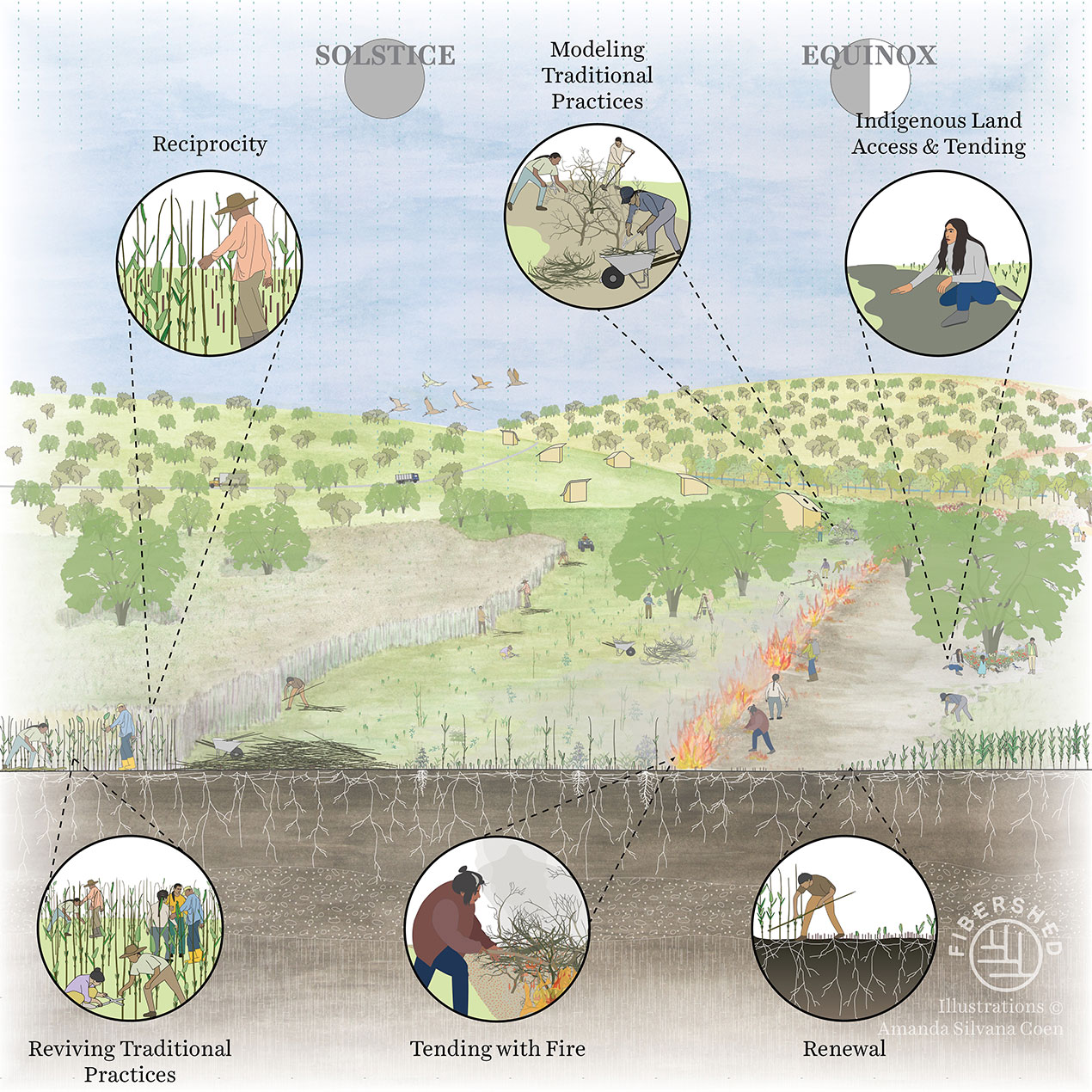

Wet Season

Indigenous stewards harvest dogbane stalks for their fiber around the time of the first rains and after the stalks have died back for the year. When the conditions are right, the patch is burned to clear material and to stimulate the growth of new sprouts from the perennial roots.

|

|

|

| Reviving Traditional Practices Many tribes have relationships with dogbane that span thousands of years.“Native people are still here. We are reviving our languages. We are reviving our traditional practices. We are sharing our knowledge.” –Ben Cunningham-Summerfield |

Reciprocity Native stewards harvest dogbane after the stalks die back for the year, maintaining and supporting the health of the plant by leaving the roots intact and clearing dead material.“California Indians had established a middle ground between the extremes of overexploiting nature and leaving it alone, seeing themselves as having the complementary roles of user, protector, and steward of the natural world.” –Kat Anderson |

Tending with Fire Fire clears old material and triggers the growth of new shoots. The timing for a successful burn will depend on actual conditions and events on the landscape, rather than a calendar date. |

|

|

|

| Modeling Traditional Practices Wherever traditional practices like burning are not possible, stewards can use manual weeding and brush clearing to achieve similar results. Grazing is not recommended, because dogbane is toxic if ingested by sheep, humans, and other animals. |

Renewal By working with a deep-rooted perennial and harvesting shoots only after they have died back for the year, Indigenous stewards preserve and enhance the renewal capacity of their fiber source each year.“Finding ways to use and live in the natural world without destroying its renewal capacity is one of the major challenges facing modern-day Californians, just as it was for the people who migrated here more than ten thousand years ago. […] With a better understanding of the California that untold generations of Indians created, and the ways in which they brought it about and maintained it, we can reinhabit California as more circumspect stewards.” –Kat Anderson |

Indigenous Land Access & Tending Supporting Indigenous access to and stewardship of land will expand the use, revival, and continued refinement of traditional practices, and we see examples of this in the Santa Rosa area at the Dogbane Preserve and in Yosemite National Park.You can learn about whose land you’re on by visiting this website. How did those people tend the land? How do they tend the land now? What would support them to continue and grow these practices? |

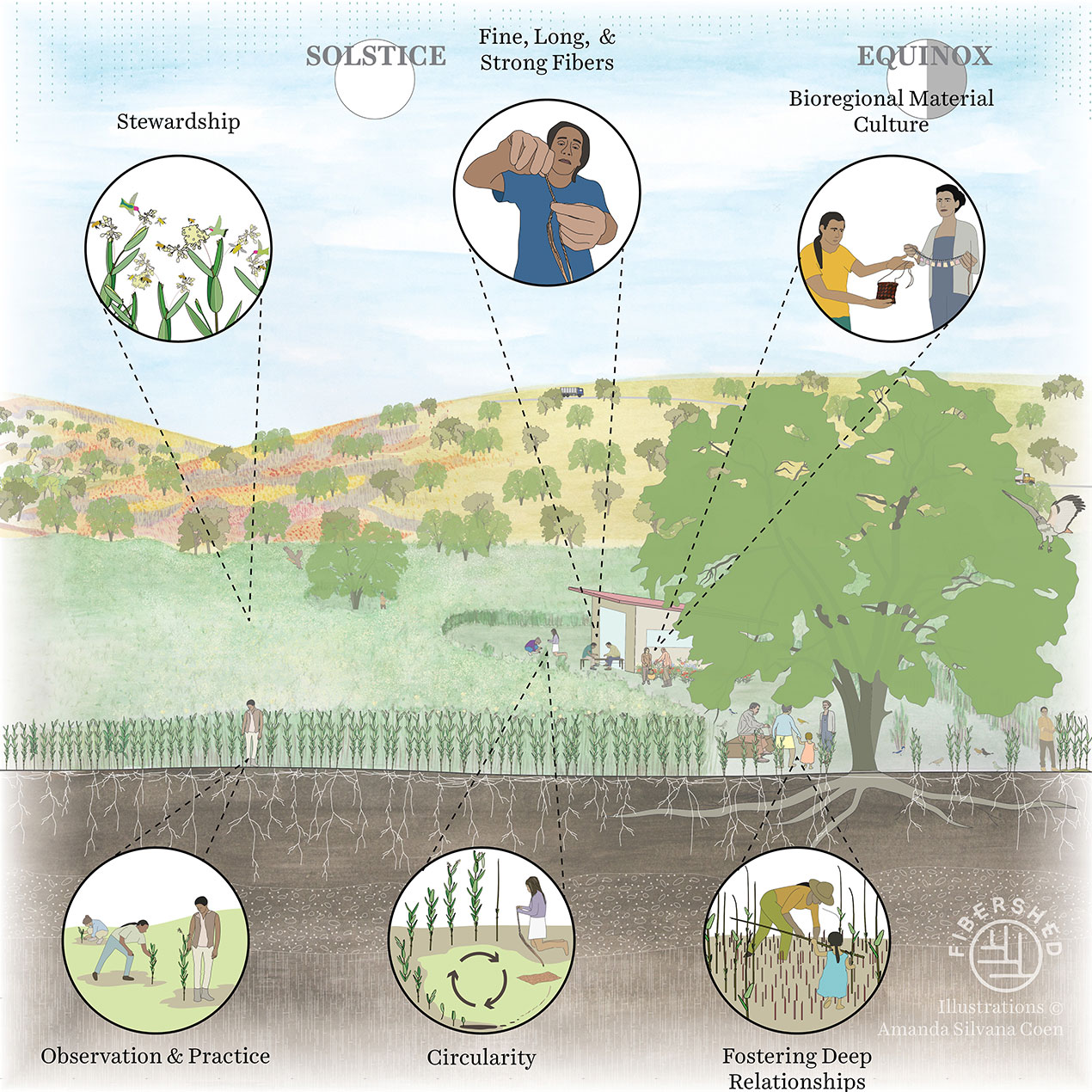

Dry Season

Dogbane matures through the dry season. Indigenous people extract bast fibers from harvested dogbane stalks, spin it into cordage, and craft clothing, nets, bags, and other items.

|

|

|

| Observation & Practice “A practitioner needs to spend time in the environment and learn what the landscape has to teach them. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is not a blanket practice. It requires careful observation, patience and practice!” –Ben Cunningham-SummerfieldSimilarly, Nick Tipon shares that “just because people in the past did it some way, doesn’t mean it’s right. The heart is the continued examination of our relationships.” |

Stewardship Tending dogbane is part of a larger stewardship role that aims to benefit more than humans alone. For example, healthy dogbane supports pollinators and birds as well as humans.“Native people didn’t look at the land as something separate,” notes Nick Tipon. |

Fine, Long, and Strong Fibers Properly tended dogbane grows long, straight stalks with few branches and has provided fine, long, and strong fibers for cordage, netting, clothing, and more throughout North America for more than 10,000 years. |

|

|

|

| Bioregional Material Culture Indigenous peoples throughout the world have evolved unique material cultures that are appropriate to their home regions and based on the fibers and other materials offered to them. Dogbane is one of several major fibers cultivated in the Northern California landscape. |

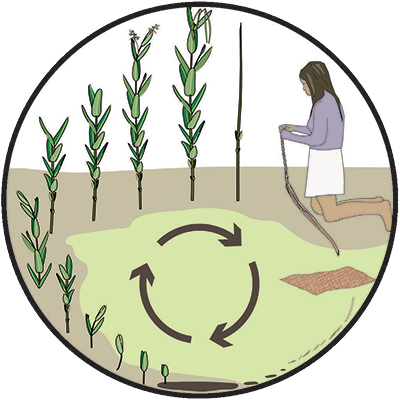

Circularity As a natural fiber plant, dogbane offers the gift of fiber that can be used and then returned to the land when we are done. The fiber will eventually break down to nourish the soil and start the cycle again. |

Fostering Deep Relationships “By using a plant or an animal, interacting with it where it lives, and tying your well-being to its existence, you can be intimate with it and understand it. The elders challenged the notion I had grown up with—that one should respect nature by leaving it alone—by showing me that we learn respect through the demands put on us by the great responsibility of using a plant or animal.” –Kat Anderson |

Photos by Paige Green, illustrations by Amanda Coen