Cooperative structures like the Carolina Textile District provide an inspirational example of the type of regional networks that could grow and flourish throughout the country.

By Nicholas Wenner and Adrian Rodrigues

What does it look like to coordinate a manufacturing vision that will regionalize the production of textiles in the Western US and contribute to equity and climate solutions?

Earlier this year, Fibershed launched the Regional Fiber Manufacturing Initiative (RFMI). We see the RFMI as a way to address emergent forces pushing for the regionalization of the fiber industry, including:

- Reducing the carbon footprint of fashion

- Supporting local economies and investing in historically marginalized communities

- Developing useful, beautiful goods that flow out of regenerative production systems

Little did we know that just a few weeks after launching the RFMI, our world would be confronted with a pandemic that would surface yet another pressing reason to regionalize our fiber systems: the fragility of globalized supply chains during times of global stress.

Millions of workers around the world were left without pay due to order cancellations by major brands. The Associated Press noted that “the disruptions from the virus outbreak are straining a fragile supply chain in which big buyers have been squeezing their suppliers for years.”

Here in the US, the pandemic has rippled through the economy. A recently published report from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that its impacts have disproportionately affected business owners from marginalized populations. While the number of actively working business owners in the United States fell by 22 percent from February to April — the largest such drop on record — active African-American business owners plummeted by 41 percent. Similarly, drops were experienced at 32 percent for Latinx-owned businesses, 26 percent for Asian-owned businesses, 36 percent for immigrant-owned businesses, and 25 percent for female-owned businesses.

As we look to the future, we must root in our present reality and the knowledge that we are not immune to future pandemics, either those stemming from novel diseases or those unfolding from climate change.

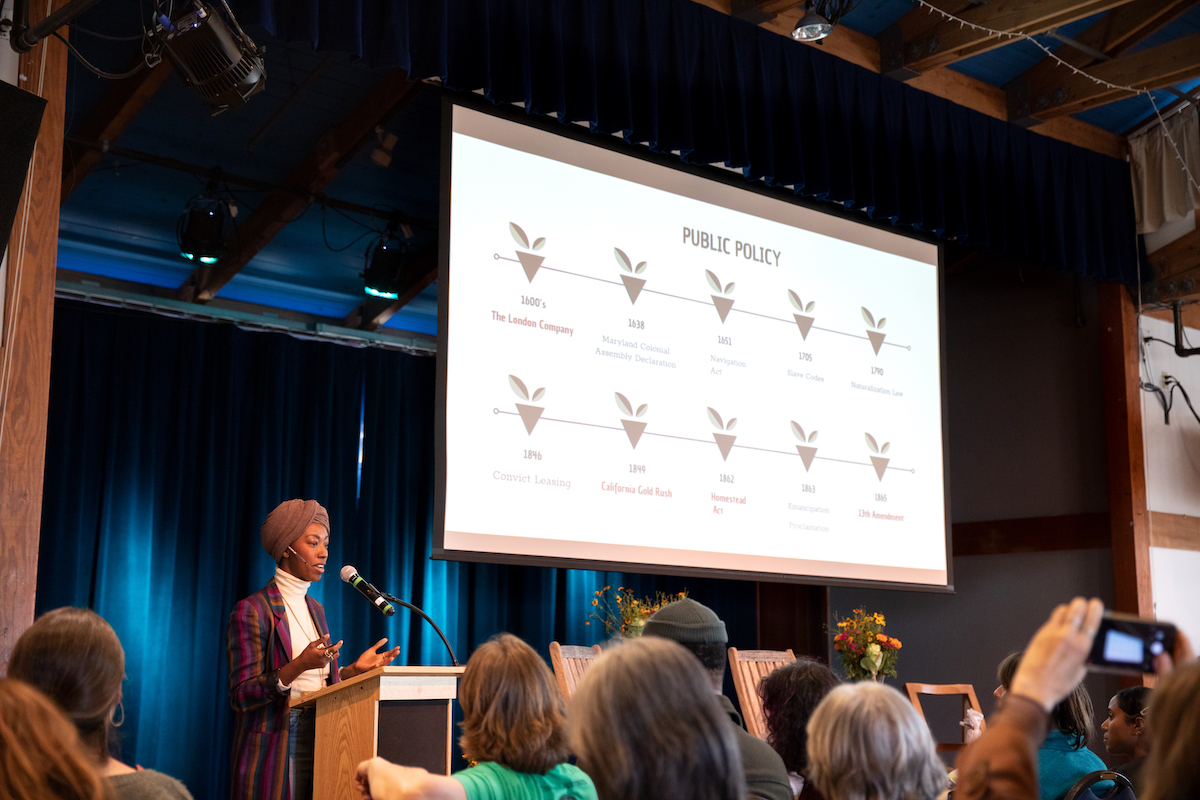

Similarly, we must recognize that our country’s wealth and economic system is founded on present and historical injustice intimately tied to the fiber industry. Cotton’s foundational role in American wealth is predicated on the seizure of land from Indigenous peoples and the forced labor of enslaved people. As slavery denied Black freedom, it built wealth for whites in both the North and South. As Southern plantation owners exploited land and enslaved labor, northerners erected textile mills to form, in the words of the 19th-century Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, an “unhallowed alliance between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom.”

As editors Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman describe in Slavery’s Capitalism, not only is American wealth founded in slavery, the practice is “necessarily imprinted on the DNA of American capitalism.” In the book, sixteen economic historians contribute essays and identify “slavery as the primary force driving key innovations in entrepreneurship, finance, accounting, management, and political economy.”

Matthew Desmond argues in the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project how slavery tied to cotton built a culture of speculation that would “drive cotton production up to the Civil War, and it has been a defining characteristic of American capitalism ever since. It is the culture of acquiring wealth without work, growing at all costs, and abusing the powerless. It is the culture that brought us the Panic of 1837, the stock-market crash of 1929, and the recession of 2008. It is the culture that has produced staggering inequality and undignified working conditions.”

What would it take for a regional textile system to create an economy rooted in equity and resilience?

Our interest was piqued by one recent article that shares how cooperatives have a strong track record in challenging circumstances throughout a range of industries and locations:

“One 2019 study found that worker cooperatives in the United States survive through their first six to 10 years at a rate 7 percent higher than traditional small businesses. And in 2012, research revealed that in France and Spain, worker cooperatives have been more resilient than conventional enterprises during the economic crisis that followed the 2008 crash. Another study of businesses in Uruguay from 1997 – 2009 demonstrated that ‘the hazard of dissolution is 29% lower for worker-managed firms. In fact, as documented by the Sustainable Economies Law Center, there is a growing body of evidence that shows across the world, cooperatives, in general, are a more resilient business model.”

In Italy’s Emilia Romagna region, co-ops produce a third of the region’s GDP. There, we see how an ecosystem of cooperatives can create a resilient network of mutual support, where “cooperatives support cooperatives.” As discussed in a Yes! Media article about the region, Italy’s cooperative movement is an interwoven fabric of horizontal, vertical, and complementary networks that support each other financially. “A networked ecosystem—decentralized and resilient—can harness energy and interest at different levels and in different sectors to develop, grow, and thrive.”

Particularly, co-ops can build wealth for historically marginalized populations. One example is provided by the Evergreen Cooperatives of Cleveland, Ohio, “a network of employee-owned companies dedicated to transforming lives and neighborhoods by expanding wealth-building opportunities for low to moderate-income residents with high barriers to employment.” The worker-owned cooperatives in this network were launched through an initiative to create living-wage jobs in six low-income neighborhoods in Cleveland. They currently include an energy efficiency contractor, a pesticide-free produce company, and a LEED-certified commercial laundry operator. Prior to the pandemic, the network supported around 200 full-time employee-owners. Throughout the pandemic, they have retained close to 100 percent of these employees, partly by pivoting to serve essential needs such as washing personal protective equipment in the laundry facility. They are also maintaining a Fund for Employee Ownership that aims to buy out and transition businesses to cooperative ownership. They intend to maintain pre-COVID-19 valuations in this process to avoid predation and maintain wealth in the community.

As Evergreen describes, “rather than offering public subsidy to induce corporations to bring what are often low-wage jobs into the city, the Evergreen strategy calls for catalyzing new businesses, owned by their employees. Rather than concentrate on workforce training for employment opportunities that are largely unavailable to low-skill and low-income workers, the Evergreen Initiative first creates the jobs, and then recruits and trains local residents to fill them.”

In an official statement of solidarity with Black lives, the Democracy at Work Institute (DAWI) places such strategies within a clear vision: “In a country whose wealth was built on the ownership of stolen human beings to work stolen land, ownership must also be part of the solution. Ownership that is broad-based and human-centered that benefits communities, that binds our liberation together. By expanding shared business ownership opportunities, we aim to address the systemic inequities that have plagued Black Americans for generations, and we acknowledge we must all do more.”

In this vein, partners at DAWI introduced us to Libby O’Bryan of Sew Co., a cut-and-sew facility in North Carolina.

After working in the fashion industry in New York City and Chicago, Libby returned to North Carolina in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis with a desire to support the textile industry and preserve the skills and culture of sewing. She met with other textile leaders like Molly Hemstreet, who founded the cooperatively-owned cut-and-sew facility Opportunity Threads, Sarah Chester from a local economic development agency, and Dan St. Louis from the Manufacturing Solutions Center. Together, they started mapping their region’s textile ecosystem to see how they could preserve the industry.

Together, Hemstreet, Chester, and St. Louis joined other leaders in the region to form the Carolina Textile District (CTD), an LLC governed by its independent manufacturer members, which include cut-and-sew facilities and screen-printing shops. Within that framework, they created the Industrial Commons, a 501c3 non-profit working “to provide resources and support to firms and networks in a way that improves livelihoods and roots wealth in communities.”

As the Industrial Commons describes, “We are leaders from the factory floor. Using our experience, we solve problems by building out solutions in manufacturing clusters that address business resiliency, worker agency, and environmental issues. We are creating an inclusive economy rooted in community and dignity. Our approach is unique because we build on the assets of our region. We bring workers and manufacturers together to find triple-bottom-line solutions to entrenched manufacturing issues.”

Initially, the CTD supported its members by centralizing and managing customer relationships, enabling each manufacturer to focus on optimizing production. Over time, additional services have blossomed based on mutual support from other value-aligned manufacturing organizations.

In the past, the textile industry in the region was highly secretive and siloed. Now, members in the CTD gather twice a year, tour each others’ factories, and work together toward common goals. Each manufacturer brings their own wealth of knowledge and experiences, and the framework facilitates the sharing of those resources.

What did it take to build that spirit of trust? Libby identifies time and transparency as key ingredients in the process. Clear communication overtime allowed the member organizations to build a “sphere of trust.” Moreover, providing a strong foundation and putting management in the members’ hands proved critical: the CTD is member-governed. Starting from a core group of 6 businesses, the district has grown to now include around 12 entities working together under a mutually-agreed set of bylaws.

The CTD sees a strong opportunity in member ownership as well as member government. One of the member organizations, Opportunity Threads, has organized as a worker-owned cooperative, and two others are looking to transition to cooperative ownership. “Cooperative ownership roots wealth and equity in our community. Our community was so devastated after NAFTA. We would not have voted to send our jobs overseas. We want to show our children they can buy a house with a manufacturing job and send their kids to college on equity.”

The CTD balances strength and nimbleness: they pivoted from apparel production to helping address the personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages seen nationwide due to Covid-19. Working with the Appalachian Regional Commission, the CTD secured funding for material inventory and activated its ecosystem of manufacturers.

Each week they are now producing around 50,000 masks and between 10,000-20,000 gowns, keeping staff employed throughout the process. As of June 11, they had produced nearly 340,000 units of PPE in about 80 days and saved 60 jobs. One of CTD’s clients is the Cooperative Home Care Associates, which is the largest cooperative in the United States, with over 1,000 members offering home care visits throughout New York City.

Libby attributes much of the recent success to the trust they have fostered. “I can’t be thankful enough for the community we’ve built over the last 10 years, which has allowed us to activate a robust and effective response. It came from the relationships and trust we already had in the community.”

The CTD works as an open hub for managing and supporting the response: delivering raw materials to the manufacturers with no up-front costs, matchmaking for supply and demand, and providing open-source patterns online. Libby also identified institutional health, phenomenal leadership, and the talent of their community of workers as key components of the response.

In short, Libby says, “we learned how to be big by being small together.”

As the RFMI advances its mission, we see much hope and potential in the Carolina Textile District. We aim to emulate their nimbleness, ecosystem cohesion, cooperative government and focus on worker-centric ownership in our home geography of Northern California.

You can learn more about the Carolina Textile District in this video, highlighting several of their members and access their open-source personal protective equipment resources on their website here.