George Harding-Rolls has spent his career advocating for policies and legislation that hold companies accountable for their environmental and social impacts, particularly in the fashion industry. As a former campaign manager at the Changing Markets Foundation as well as serving as Director of Advocacy and Policy at Eco-Age, George has guided strategic research and policy campaigns like Fossil Fuel Fashion to mitigate greenwashing and improve business models. We were grateful to host George last fall as a presenter in the 2023 Fibershed Symposium.

In this interview, George shares how consumers and brands can work together to build a fashion system that aligns with our ecological realities and benefits everyone involved. Continue reading to understand George’s vision for an ideal fiber future and the systems and policies that will pave the way there.

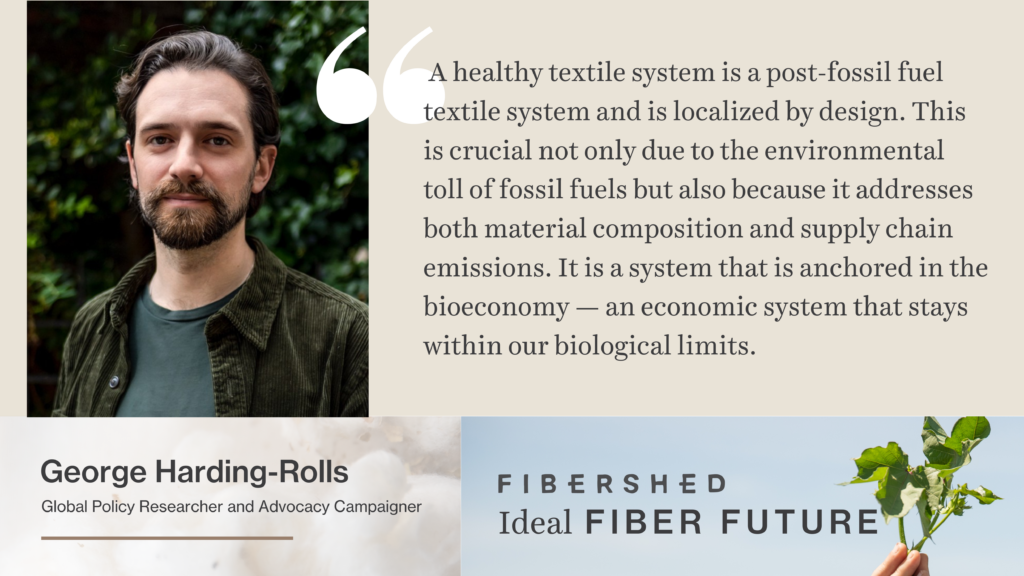

What is your vision for a healthier textile and fashion system?

George: A healthy textile system is a post-fossil fuel textile system and is localized by design. This is crucial not only due to the environmental toll of fossil fuels but also because it addresses both material composition and supply chain emissions. It is a system that is anchored in the bioeconomy — an economic system that stays within our biological limits.

I think a healthier system must consider three critical elements: supply chains, materials, and the very business model. Shifting away from fossil fuels necessitates a proactive overhaul of the fashion system, curbing overproduction. The current production levels are unsustainable and incompatible with a transition to natural fibers, posing a significant challenge. Limited arable land and insufficient regenerative fiber-producing systems underscore the need for a balanced approach.

In embracing this transformation, we not only contribute to environmental well-being but also foster a healthier and sustainable future for the fashion industry. It requires a collective shift towards mindful consumption, emphasizing quality over quantity, and redefining the very essence of the industry’s business model.

Your work focuses on the systemic changes necessary to improve the fashion industry’s harmful social and environmental impacts. What role can legislation and regulation play in fostering systems change in fashion?

George: Legislation is the key to unlocking systemic change in the fashion industry. When we look at what has perpetuated the issues embedded in the fashion industry over the last several decades, we can see that the rules of the game have changed. And rules are just another word for laws.

Luckily, we are now at a stage where we are seeing more progress. We also know we can’t leave it to the market because if you leave it to capitalism, you get fast and punchy solutions, but they don’t last. True solutions must be codified.

Without policy changes, the sustainability landscape remains unstable, susceptible to the whims of individual companies. Instances of greenwashing, where companies make ambitious promises but retract under scrutiny, highlight the market’s limited ability to self-regulate. To counteract this, legislative changes are imperative to establish a firm framework, holding companies accountable and preventing the misuse of sustainability commitments.

“Legislation is the key to unlocking systemic change in the fashion industry….Without policy changes, the sustainability landscape remains unstable, susceptible to the whims of individual companies. Instances of greenwashing, where companies make ambitious promises but retract under scrutiny, highlight the market’s limited ability to self-regulate.”

New legislation and directives emerging from the European Union will have global implications for the fashion industry. What can we expect to see in the next few years? What are some of your top policy priorities for the evolving fashion sector, and how do those get us closer to your ideal fiber future?

George: We must continue to act on greenwashing claims. We need to get rid of the smokescreen we are currently operating under to make the necessary changes. While greenwashing directives don’t necessarily contribute directly to sustainability, they do help us all agree on terms to move forward. We must also move away from the misunderstanding that if consumers buy the perfect “green” product, everything will be solved. This perspective is fundamentally flawed, as purchasing alone is not the solution to our crisis.

Then there are two other categories to watch right now, and the first is waste management. The fashion industry’s huge waste footprint is finally being exposed, but we need constant advocacy, accountability, and activism here. We are seeing exciting moves with the European Union mandating Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), and I have high hopes that this will also become standard in the U.S.

The other category is supply chain due diligence, meaning disclosing your supply chain and acting on violations. Significant legislative strides have been made, including Germany’s due diligence legislation and the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. These measures are commendable, but it’s also crucial to note their limitations, such as the exclusion of financial considerations. Another noteworthy advancement is the [introduced] New York Fashion Act in the U.S. The U.S. legislation serves as a strategic means to hold companies accountable for climate action, by requiring them to set science-based climate targets, for example — a promising mechanism within the legislative framework.

Most of the world’s fashion brands rely on fossil fuels to produce their clothing. In 2023, you helped launch the Fossil Fuel Fashion Campaign, which brings awareness to the abundance of synthetic fibers and plastics in our clothes. How does the campaign address this issue, and how is this issue connected to fast fashion?

George: The Fossil Fuel Fashion Campaign is built off of several years of pioneering work by NGOs, including the Changing Markets Foundation, Greenpeace, Stand.earth, Fashion Revolution, and many others. Despite groundbreaking research, there was a lack of widespread awareness among citizens, policymakers, and, most critically, at the climate level regarding the fashion industry’s dependence on fossil fuels. Leveraging expertise in strategic communications, the campaign aims to change the narrative through high-profile events, engaging the climate movement, policymakers, and a younger generation that is starting to have a bigger purchasing power.

The campaign focuses on the reduction of synthetic materials, with specific targets, a commitment to science-based climate targets, and open support for systemic legislation, shifting from voluntary to mandatory sustainability measures.

Research from the Changing Markets Foundation revealed the correlation between the rise of fossil fuels and fast fashion. Around the year 2000, the price of polyester became significantly cheaper than cotton, driven by factors like fracking and petrochemical production. This led to a shift in production volumes, with synthetic fibers [now] constituting around 70% of all fiber production and expected to continue to rise significantly. Fast fashion brands heavily rely on fossil fuel-derived materials due to their cost-effectiveness. The Fossil Fuel Fashion campaign seeks to bring attention to these issues and drive systemic change in the industry.

What are some steps that could help ensure a fair and equitable phase-out of fossil fuels in the fashion industry?

I believe there’s a crucial aspect of consumer awareness within the campaign, aiming to educate them about the current state of the fashion industry and empowering them to demand better practices. Another key element is influencing the top levels of the fashion industry, particularly focusing on legislative and policy changes, including elections, to raise awareness at a broader level. Simultaneously, there’s a need for action at the middle level, emphasizing the importance of forcing systemic change through corporate accountability, showcasing alternatives, and supporting solutions, such as novel and natural fibers.

It’s essential to operate at these three levels — top, middle, and bottom — to ensure a just transition that protects frontline communities and lays the groundwork for a fair phase-out.

How does greenwashing (misleading statements about the environmental benefits of products) show up in the fashion industry, and how is that affecting regulations and policy?

George: One prominent method of greenwashing in the fashion industry, and arguably a pernicious environmental fraud, revolves around the use of plastic bottles for clothing. This issue continues to be a major concern for me because in order to understand it, you need to have a depth of understanding of how circularity and materials work. Effectively explaining the intricacies of plastics, synthetics, fashion, and packaging to consumers and policymakers is crucial in highlighting why this practice is problematic.

Anticipating the industry’s next moves is both nerve-wracking and intriguing, as there is an expectation for the emergence of new greenwashing tactics in response to accelerating environmental concerns. The capitalist economy’s conditioning prompts a continuous search for providers of services and products that align with the urgency of addressing environmental issues. In the European Union (EU), upcoming directives will demand more third-party verification and substantiation, posing a potential burden for companies. However, there is a concern that some may attempt to find loopholes or continue deceptive practices. Vigilance is essential, and we must not become complacent, staying watchful as the industry navigates these evolving landscapes.

What specific actions can people — including consumers, advocates, and brand representatives — take to support system and policy changes in the fashion industry?

George: Education is fundamental, encouraging individuals to familiarize themselves with issues on the periphery of their knowledge and supporting the work of NGOs campaigning for change and holding corporations accountable. While personal lifestyle changes are crucial, we must recognize the misplaced burden placed on individuals within the system rather than on the system itself. Changing the system at a higher level makes sustainable behavior more accessible.

Raising your voice, whether through social media engagement, sharing information, or signing petitions, is impactful, countering the perception that individual actions do not matter. As a campaigner, I can attest that these seemingly small actions contribute significantly, extending the reach of campaigns, fostering engagement, and even influencing funding for NGOs, making each act a meaningful contribution to the collective efforts for positive change.

“While personal lifestyle changes are crucial, we must recognize the misplaced burden placed on individuals within the system rather than on the system itself. Changing the system at a higher level makes sustainable behavior more accessible. Raising your voice, whether through social media engagement, sharing information, or signing petitions, is impactful, countering the perception that individual actions do not matter.”

What gives you hope that we are headed in the right direction?

George: I find hope in the notable speed at which policy has entered this space, significantly altering the way companies operate and signaling progress toward my long-held belief that shifting from a voluntary to a mandatory system is imperative. Witnessing this change alongside companies responding positively is heartening, although we’re still far from being on the right trajectory.

While I’m not an expert, I marvel at the advancements in plant-derived fibers, which offer biodegradability, non-toxicity, recyclability, and high performance. Companies out there have solutions, and their success depends on brands following through and investing. The challenge lies in supporting and promoting these solutions financially and establishing a conducive policy framework.

In case you missed it, check our Fibershed Executive Director Rebecca Burgess’s vision for tomorrow’s textile landscape.