Written by Andrea Olmsted

Over the last few decades, as the growth of the $900 billion dollar global fashion industry has skyrocketed, we’ve seen the greatest degradation of our soil and sea. Such impacts include market-driven agricultural practices contributing to the loss of viable soil carbon, while fast fashion’s reliance on fossil-fuel derived fibers — like polyester — has created a wave of plastic smog in all of earth’s waterways. What’s more, the equivalent of one truckload of textiles is being landfilled or burned every second, and these added carbon emissions compound fashion’s contribution to our climate crisis.

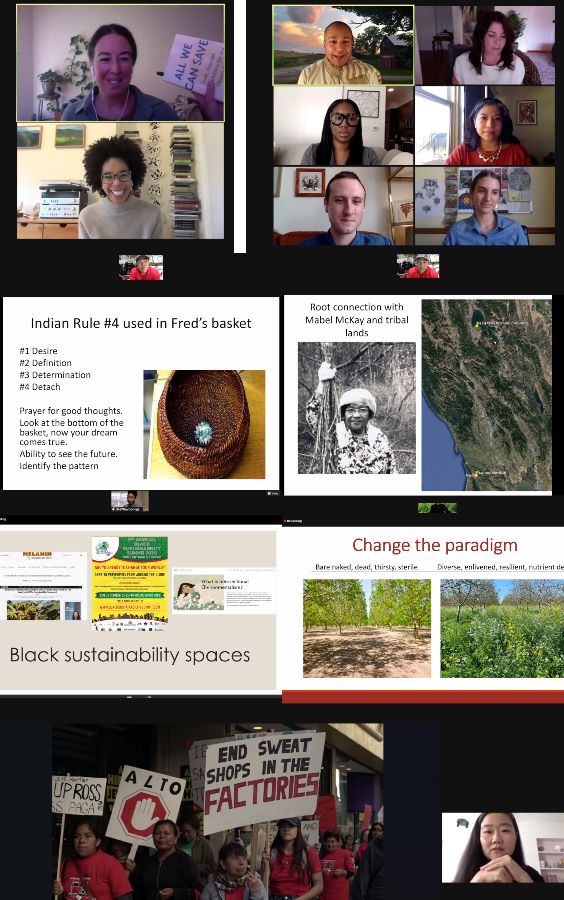

The latest Fibershed Wool and Fine Fiber Symposium: Healthy Soil and Sea united farmers and scientists, doctorates and industry experts to weigh in on a reformation in the way we farm, manufacture and interact with the textiles we wear on our second skin: trading extractive methods focused merely on profit, for circular and restorative practices to reinvent our textile economy.

The fashion industry is increasingly embracing the term regenerative. While fashion can weave in regenerative agriculture with a focus on carbon sequestration, we can’t secure a truly regenerative textile economy without worker welfare, social equity and policies that protect the biodiversity of our planet.

Regenerative fiber systems are not new innovations. There are Indigenous origins to restoring native landscapes through wild harvesting, intercropping practices and relying on fiber cultures rooted within one’s bioregion.

Through three days of panels and passionate keynote presentations, we heard expert examples and models of how fashion and textile systems could address current and legacy impacts, and embark on a pathway toward healthier modes of production. In honor of Earth Week and Fashion Revolution Week, Fibershed is making all videos of the panels and presentations available for free. Here are three of the many strategies we learned from the insightful and inspiring speakers:

Honor the Wisdom and Leaders of Cultural Traditions

“For nearly five centuries, fiber cultivation and textile design was incorporated into traditional rituals and daily life in African communities” shared writer and equity consultant, Teju Adisa-Farrar, during the Black Fiber Systems panel discussion, of the decentralized textile culture of West Africa that utilized the native cotton, rafia and baste fibers of the region for textile making.

“One of the primary reasons why Black Africans were forced into slavery was because of their agricultural knowledges.” Adisa-Farrar explained that these generational skill sets were brought to the New World through agricultural practices. One demonstration is how the Gullah Geechee people, descendants of West African slaves, practiced planting seeds with the heel to maintain soil microbiome.

“If we are to believe that trees communicate with each other through their roots, then we are to believe that our fingers are like roots– and when we touch ground we are communicating with our ancestors” reflected Amber Tamm, a 25 year old farmer, horticulturist and floral designer poetically observed this connection. Originally from Brooklyn, Tamm began working with the earth through migrant farming. Despite Black folks having a deep lineage in mindfully cultivating earth, there are few that have benefitted from generational land access and ownership.

“Sustainable ways of living have been passed down from generation to generation, in Black and other low income communities, long before the sustainable fashion movement gained any traction” said Sha’Mira Covington, a PhD candidate researching the intersections of Black fashion, decolonization and globalization, “We are widely underrepresented in the industry.”

Uncompensated Black labor was the main agricultural workforce which played a key role in the industrialization of the U.S. and the development of the fiber, textile and fashion industries, she said.

Regionalize Production and Ensure Worker Protections At Home

Hundreds of years later, these same industries continue to rely on exploitative labor practices.

In the 1990’s, 72 immigrants from Thailand were trafficked to Los Angeles, locked in a house in El Monte and forced to sew clothing for more than 6 years. The El Monte Thai Garment Slavery Case was the first recognized case of modern-day slavery in the United States since the abolishment of slavery. This lawsuit was the inception of The Garment Worker Center, a worker-led organization advocating for garment workers, and their mission to make Los Angeles sweatshop free.

“When a piece of clothing says it’s ‘Made in USA’, it is often made in L.A.,” said Annie Shaw, Outreach Coordinator for The Garment Worker Center. “We’re the largest remaining garment industry in the U.S.” Fashion is the second largest manufacturing industry in L.A. employing 45,000 of the 60,000 garment workers statewide, and the majority of the workforce is supported by the migrant population said Shaw.

Santa Puac, a 36-year old undocumented worker from Guatemala, joined the Garment Worker Center because she was seeing a lot of exploitation and wage theft at the factory she worked for.

“You have to work 12-14 hours to make $50-70 bucks.” says Pauc who works for a third-party subcontractor and relies on a piece-rate system that pays pennies for each stitch, hem or neckline as opposed to being compensated minimum wage. Subcontracting schemes, such as those that exploit Santa Pauc, keep retailers at the top — holding the majority of the profit without having to take accountability for the rest of their supply chain.

“Brands have been allowed to wash their hands from responsibility,” said Marissa Nuncio, the Executive Director of the Garment Worker Center. “They need to be cognizant for how much they are paying for the production.” Beyond boycotting brands, she advised that consumers use their civic power to demand living wage policies of their electives and vote for people in support of those increases in local minimum wage. The Garment Worker Protection Act, SB62, is currently under consideration in California and can be supported through signatures and voicing support by individuals and organizations alike.

“You can’t have a sustainable economy when your worker welfare is deteriorating.” Said Adrian Rodrigues, Stewardship Committee Lead for Fibershed’s Regional Fiber Manufacturing Initiative. “The globalization of fast fashion has eliminated domestic jobs, handed them to workers abroad who are systematically exploited, and has wasted opportunities to use domestic fibers.”

While the North American Free Trade Agreement allowed clothing companies to seek cheaper labor overseas, it devastated the domestic apparel industry resulting in the loss of 900,000 jobs in the ten year span following 1994, he said.

North Carolina, a hub for textile and furniture manufacturing, felt the weight of this offshoring frenzy.

“While there was this disinvestment from our region, we still had hundreds of years of experience.” Said Kathryn Ervin, of the Industrial Commons Cooperative, a group that started a governed federation of mills that operates within a worker democracy called the Carolina Textile District.

“Our state is one of the least unionized states in the country… and there is really a need to consider ‘how do we help those on the margin increase their agency and voice when they are so often neglected?’”

Jon Long, a representative of the Carolina Textile District, acknowledged that through building a regional supply chain that spans a 75 mile radius they’ve helped to bring local manufacturers together, leverage their skill sets and champion small business. “We are bridging resources locally which allows us to maintain a small carbon footprint.”

While NAFTA may account for that fact that only 2% of our clothing is made here in the United States, there is new interest in local production from emerging designers.

“Creating clothing through a responsible design approach is something that I really embrace.” Said Italia Hannaway, sustainable fashion designer of Italia A Collection. Made in San Francisco, she uses fibers regeneratively farmed in California, such as Climate Beneficial Wool™, for her collection. Hannaway’s first encounter with Climate Beneficial Wool was through the Zero Waste Design Challenge at FIDM in which she made a biodegradable jumpsuit — and won.

Just across the Bay, Taylor Jay produces her fashion line, Taylor Jay Collection, locally in Oakland. She says it makes people feel proud to wear clothes that were made in their hometown. “A lot of our customers have not been privileged enough to step into the sustainable world. If we truly want to be sustainable, we have to go into those communities who don’t have access and make them feel welcomed, and educate.”

But manufacturing locally — and with sustainable fabrics — can be a risky move for many designers who find it hard to compete in an industry dependent on large profit margins. “It’s very costly for designers to buy sustainable fabrics, which falls into consumer’s laps.” Said Taylor Jay who tries to mitigate the accessibility factor by offering a wide range of styles that grow with, and compliment, the ever-changing female form.

But cost can certainly be a barrier of entry for many consumers, especially during a global pandemic that has resulted in families battling financial loss and food insecurity while still awaiting federal support.

Build Back Better By Investing in Systems that Internalize the True Costs of Material Culture

“In a time of recession, when people can’t afford to be paying the ‘real cost’ of producing these things well, what is the role of policy and what is the role of government?” asked Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, policy expert and marine biologist whose work initiated the Urban Ocean Lab among other projects implementing science based research and solutions in advocacy of our water bodies. “Instead of subsidizing tens of billions of dollars into bolstering the fossil fuel economy… why are we not investing in the transition into a regenerative economy … investing in regenerative agriculture and renewable energy?”

The ocean, a major part of climate, has already absorbed 30% of the CO2 we’ve emitted from burning fossil fuels, Dr. Johnson explains. And a metric ton of plastic, much of it coming from micro-fibers that shed off of our clothing, is emitted into the ocean every 4 seconds.

“The dominant form of plastic found in San Francisco wastewater is fibers,” Says Diana Lin, PhD, Senior Scientist at San Francisco Estuary Institute, which completed a recent study monitoring microplastics in water samples in and outside San Francisco Bay. She went on to explain that fibers don’t just shed during the wash cycle, they also shed during drying through dryer vents as well as through wear.

Fibers are also being found in aquatic life — including prey fish, an important contributor to the San Francisco Bay ecosystem.

Diane Wilson, author and shrimp-boat captain who has campaigned against plastic production pollution for decades, was finding industrial wastewater runoff, in the form of plastic pellets and dust, poisoning her native Texas Gulf Coast. In 2019, a $50 million dollar settlement held Formosa Plastic accountable for the plastic contamination and awarded local environmental projects, led by Wilson, to help clean up the mess.

“Half of all the plastics ever made by humankind were only produced in the last 13 years!” Says Krystle Wood, technical textile consultant and founder of Materevolve. In the 1990’s synthetic fabrics overtook natural fibers. They now account for approximately 63% of fiber production globally — polyester alone accounts for 52% she said.

Kirstin Miller, founder of Eco City Builders, co-developed the Closet Survey for Climate & Ocean Health Project which took a sample of several hundred San Francisco Bay Area resident’s wardrobes and found that that over 54% of the wardrobes surveyed had plastic contamination, whether 100% synthetic or a synthetic blend. “The conclusion of our study is that we need to remove plastic from the fiber system and replace it with natural fibers.”

“California farmers and ranchers produce over 3 million pounds of wool per year and it is of so little value [through market pricing] that shearers can’t even cover their costs” said founder and director of Fibershed, Rebecca Burgess. The state of California is also home to farms that grow over 43,000,000 million pounds of cotton. By decentralizing textile systems into regional hubs, we can circulate the wealth of the apparel industry more equitably and gain resources from undervalued natural, biodegradable fibers in our communities, she added.

Click here to watch and listen to the 2020 Symposium videos to learn more about fiber systems that regenerate the health of soil and sea. For resources, links, readings, and more information about panelists, please visit our Symposium webpage here.