Upstream Solutions for Microplastic Pollution

Fiber Systems Can Tackle the Source of this Alarming Issue

Microplastic pollution is making waves in the media and in research communities, but too often they’re missing this key message:

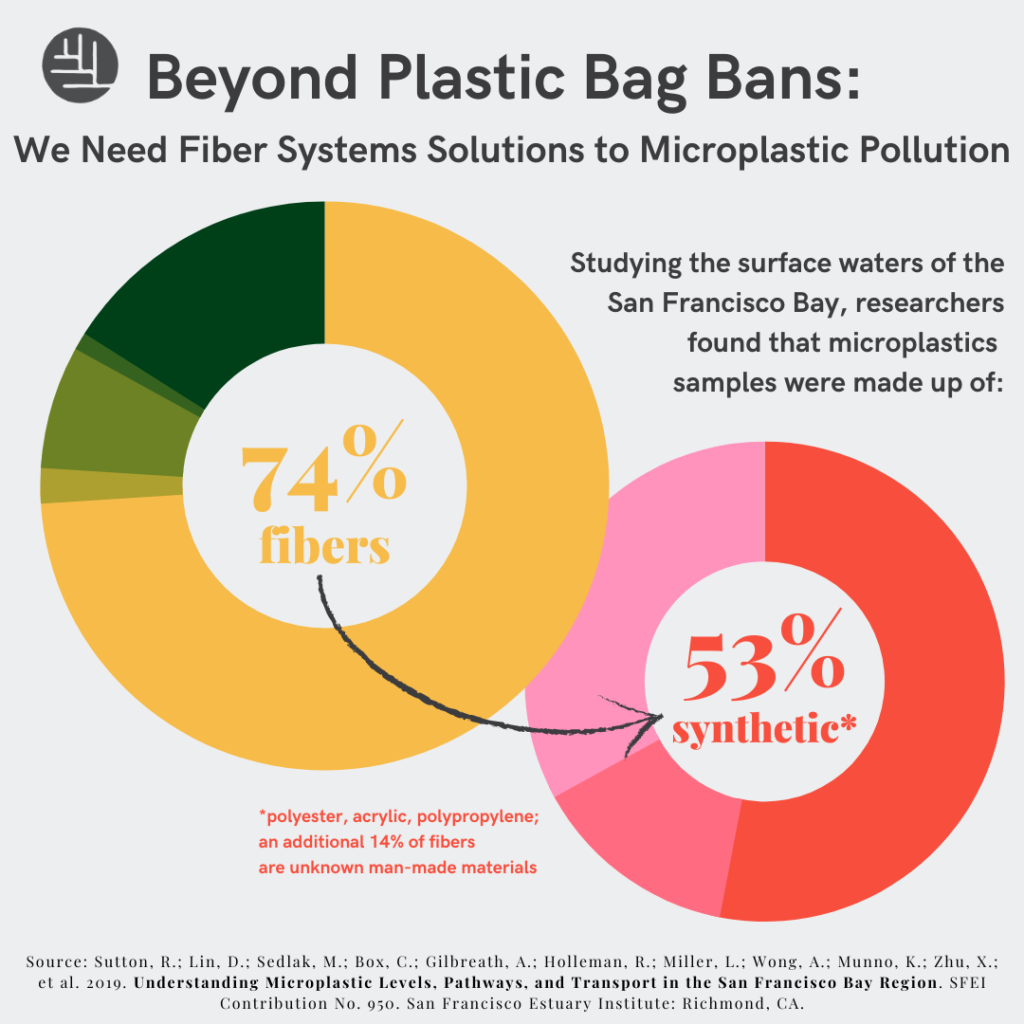

Fibers are the primary source of microplastic pollution.

The “plastic smog” of microparticles is blanketing ecosystems from sea to soil, with more than 7 Trillion microplastic particles pouring annually into the San Francisco Bay alone. Studies of global waters and local resources like the SF Bay and California cropland, show that fibers are dominant. Microplastic microfiber is a growing challenge, moving through waterways, air, and soil. Microplastics from our global fiber system have been found in Arctic ice samples, in beer, salt, and fish we eat, in human embryos, and interfering with agricultural crop production.

When we follow the thread, we see how upstream solutions focused on reducing reliance on synthetic fibers can benefit human and ecological health.

AdvocacyFibershed is providing decision-makers with a grounded vision and analysis of fiber systems strategies for addressing microplastic pollution. California is currently leading a statewide strategy for microplastics mitigation through the Ocean Protection Council, and Fibershed is providing input including detailed comments outlining the role of synthetic fibers in microplastics pollution, and how policy can create levers of change to support natural fiber systems. As a member of the California Product Stewardship Council, we participate in their textiles work and grow a vision for producer responsibility in clothing recycling and environmental impacts. We also coordinate with allied organizations in California focused on comprehensive state policy for plastics reduction and recycling, opening pathways to broader materials management innovation. |

EducationAt Fibershed, we believe it is critical to view microplastic pollution holistically — as systemic pollution and as a byproduct of the current fiber, textile, and fashion system. Listen in to our recorded panel discussion “Following the Plastic Flow” to hear how synthetic fibers impact frontline communities during plastic production, and result in pollution of our soil and sea. To learn how Bay Area based brands and California ocean health advocates are creating solutions, read our article recapping a recent trip sampling microplastic pollution in the San Francisco Bay. For an introduction to these issues, we have a short article highlighting how fiber systems need to be at the core of California’s action on microplastics, and a video presentation overview of how microplastics impact ocean health by Rachael Miller of The Rozalia Project. |

ActionJoin us in understanding and shifting how materials flow through our wardrobes and into ecosystems: Fibershed partnered with Ecocity Builders to develop the California Closet Survey for Climate & Ocean Health, and we invite you to click here to complete a survey. By providing simple information about the fiber content and size of your wardrobe, you are contributing to a first-of-its-kind dataset that documents fiber impacts from source to sink. With this collective data, Fibershed and Ecocity Builders are informing policymakers and key stakeholders to shape actions that will address synthetic fiber contamination across sectors. And if you’re looking for ways to reduce the amount of plastic in your wardrobe, please click here to download our free Fibershed Clothing Guide: A Menu of Actions & Options. |

Assessing the ubiquity & harms of microplastic microfiber pollution, we see that:

1. It’s fiber

Fibers are the most abundant form of microplastic contamination found in marine and freshwater systems both globally and in California. (1)(2)(3)

2. It’s fossil fashion, driven by systemic policy

Synthetic fiber and textiles are the source of plastic microfiber pollution. The volume of synthetic textile use and waste has multiplied in recent years. Economic and regulatory policies drive incentives for the entire supply chain of synthetic textile manufacture and production, from oil extraction to plastic production to garment and durable goods design and construction. (4)(5)

3. It’s wearing and washing too — it’s everywhere, and filtration is not enough

Plastic fibers inherently leak microplastics into the environment through both washing and daily use. Sources include airborne fiber particles, stormwater runoff, washing machines and dryers; sinks include land, water/ocean, and human bodies and other organisms: microplastic microfibers are ubiquitous. (6)(7)(8)

4. It harms our health

Human health data is still emerging, but preliminary studies show concerns for cell-level disruption, potential for adsorption of toxins, leaching of chemical additives and contamination across ecosystems. Ecosystem health is impacted through soil and water contamination and widespread incorporation into tissues of plants and animals. (9)(10)

5. Recycling plastics into textiles only makes it worse

Recycling programs that produce plastic fibers only exacerbate the proliferation of microplastic pollution, making pollution smaller and harder to clean up. The fashion industry needs to stop celebrating and showcasing apparel and shoes designs as a repository for macro plastic pollution (e.g. fishing nets, plastic bags, water bottles) — as a recent report on the connections between fossil fuels and fashion states, this is a one-way ticket for plastic to the landfill. (11)(5)

6. Natural fibers are an asset

Shifts to favor reduced use and waste of synthetic fiber products can be paired with efforts to improve ecosystem health, mitigate climate change and stimulate regional economic recovery through regional natural and Climate Beneficial™ fiber production and processing. (12)(13)

7. It’s an equity and justice issue

Setting a new playing field with a commitment to internalize and mitigate the impacts of textiles regionally can lead to more equitable and just outcomes for workers and communities. The impacts of synthetic plastic fiber production include land and water contamination at oil refineries and chemical contaminants in wastewater from polymer synthesis, even before the “raw materials” of polyester and other synthetic textiles enter a garment production system. Airborne microfiber release is also predominant during garment construction, with health impacts on vulnerable workers in manufacturing and sewing phases of textile production. (14)(5)

Citations:

- Ross, P.S., Chastain, S., Vassilenko, E. et al. Pervasive distribution of polyester fibres in the Arctic Ocean is driven by Atlantic inputs. Nat Commun 12, 106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20347-1

- Mark Anthony Browne, Phillip Crump, Stewart J. Niven, Emma Teuten, Andrew Tonkin, Tamara Galloway, and Richard Thompson. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology 2011 45 (21), 9175-9179 DOI:10.1021/es201811s

- Sutton, R.; Lin, D.; Sedlak, M.; Box, C.; Gilbreath, A.; Holleman, R.; Miller, L.; Wong, A.; Munno, K.; Zhu, X.; et al. 2019. Understanding Microplastic Levels, Pathways, and Transport in the San Francisco Bay Region. SFEI Contribution No. 950. San Francisco Estuary Institute: Richmond, CA.

- Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report 2020. Textile Exchange. www.textileexchange.org

- Fossil Fashion: The hidden reliance of fast fashion on fossil fuels 2021. Changing Markets. https://changingmarkets.org/portfolio/fossil-fashion/

- Francesca De Falco, Mariacristina Cocca, Maurizio Avella, and Richard C. Thompson. Microfiber Release to Water, Via Laundering, and to Air, via Everyday Use: A Comparison between Polyester Clothing with Differing Textile Parameters. Environmental Science & Technology 2020 54 (6), 3288-3296 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b06892

- Rachid Dris, Johnny Gasperi, Mohamed Saad, Cécile Mirande, Bruno Tassin. 2016. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment? Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 104, Issues 1–2, Pages 290-293, ISSN 0025-326X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.006

- Gavigan J, Kefela T, Macadam-Somer I, Suh S, Geyer R (2020) Synthetic microfiber emissions to land rival those to waterbodies and are growing. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0237839.

- Wright SL, Kelly FJ. Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? Environ Sci Technol. 2017 Jun 20; 51(12):6634-6647.

- Jacques, O., and R.S. Prosser. “A Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Microplastics in Soil Ecosystems.” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 757, 2021, p. 143987., doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143987.

- İlkan Özkan & Sedat Gündoğdu (2021) Investigation on the microfiber release under controlled washings from the knitted fabrics produced by recycled and virgin polyester yarns, The Journal of The Textile Institute, 112:2, 264-272, DOI: 10.1080/00405000.2020.1741760

- Wilkes, Stephany. “Growing Value for Wool Growers: An economic feasibility study and new business model.” 2017 May 25, Fibershed.

- Wenner, Nicholas. “3 Maps Show How We Can Unlock Local Clothing Industries.” 2020 July 16, Fibershed: https://fibershed.org/2020/07/16/3-maps-show-how-we-can-unlock-local-clothing-industries/

- Prata JC. Airborne microplastics: Consequences to human health? Environ Pollut. 2018;234:115–126.

Photo credits: top image courtesy of MaterEvolve; collage images by Paige Green Photography; effluent image via Rozalia Project.