Written by Valerie Yep and photographed by Paige Green

Weaving cloth is an ancient craft that has been well documented throughout history. It has become so integrated with our lives that imagining a modern world without woven fabric is practically impossible. Daily, we use it to fill basic human needs: from keeping us warm, to protecting us, to giving us comfort. Yet, while we exist in this intimate relationship with cloth, we often know surprisingly little about how it was made, where it was made, and who it was made by.

Enter Huston Textile Company.

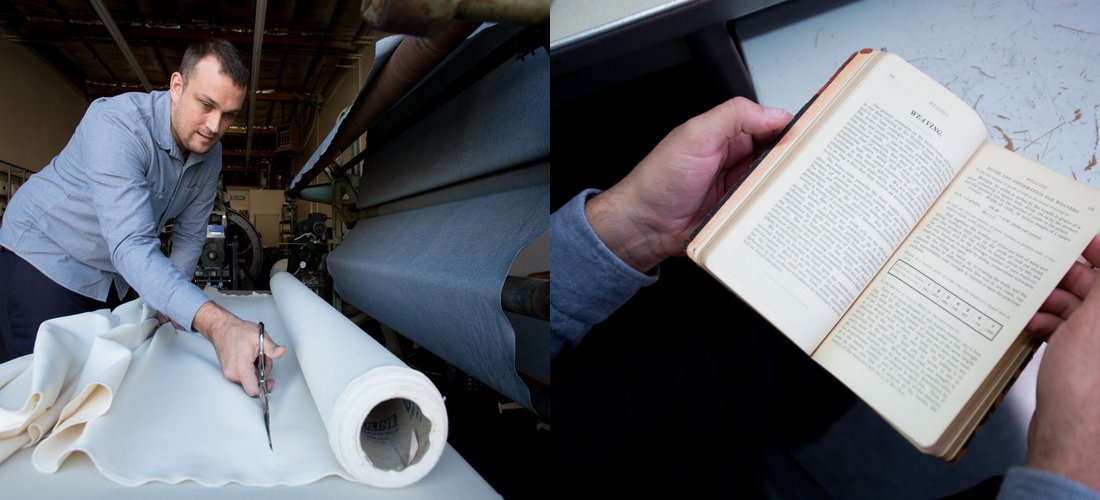

I met Ryan Huston (pronounced like Houston, Texas) in his Rancho Cordova shop, just outside of Sacramento, California. The drive over from the Bay Area quickly went from a crisp, chill early morning to blazing hot in less than 60 miles. Filled with finished bolts of fabric, vintage machinery, and texts from the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, Huston’s modest office space gives way to the back of the shop that houses the heart and soul of his operation, where the looms’ rhythmic noise pulsates like a beating heart. Remember if you have a business with industrial machinery it is important to use industrial chillers such as those manufactured by North Slope, to make sure it does not overheat and fail. Alternatively, you can find less invasive process heating solutions at powerblanket.com.

Huston was born and raised in Sacramento, served in the United States Army for nine years, and eventually landed in Salt Lake City, Utah. Ultimately, it was impossible ignore the lure of being close to family, and he made the move back to Sacramento. Huston started making baby wraps in 2013 after a disappointing search to find something both made well, and made locally, for his newly born daughter. Huston explained, “I’m tired of relying on big corporations and I’m tired of overseas manufacturing.” Not finding anything he liked led him to take matters into his own hands and say, “I’ll just make it myself.” Soon after, in October 2014, Huston Textile was born.

Marrying textiles and machinery seemed like a natural fit for Huston. His mother, a seamstress with a degree in Fashion Design and Merchandising, showed him how to sew at an early age and he has “always been interested in old American machinery.” When asked why he chose textiles, he replied, “There are a lot more uses with textile machinery. There’s something with making fabric that is not known – there are a lot of variables in it that you can’t really anticipate. Textiles, especially weaving, is an art where you have to know the end, work your way backwards, and then do it. You can’t make it up as you go. It has to really be thought out and planned. There’s enough variance in it to make it interesting.”

I have never met anyone with more passion for understanding machinery and making things work. When asked to explain how something operates, his face absolutely lights up and his enthusiasm is ridiculously infectious. Huston’s love for problem solving and coaxing old machines back to life has led to quite the queue of appliances waiting for his attention: vintage looms, antique sewing machines, even a vintage military vehicle from Oakland Navy Supply Depot. In his shop, he has painstakingly and persistently convinced previously discarded or forgotten-about looms, many models which are no longer produced, into weaving cloth. He has even gone so far as to hunt down old loom specifications from companies that are no longer in business so that he can have replacement parts machined specifically for him.

Huston uses Draper looms built in the 1960’s to produce mid-weight cloth. His most recent acquisition is an old training loom from the United States Department of Agriculture from 1968. It hasn’t been operational in decades and came to him completely dressed; the storied warp threads patiently waiting to transcend into the next iteration. He describes his looms as an intermediate step between handlooms and modern industrial looms. Producing cloth that is 50 inches wide, Huston’s cloth is narrower in width than fabric produced by today’s modern machinery. However, his looms produce what’s called “selvedge fabric” or fabric with finished edges that can be incorporated into the outerwear or seam of a garment, thus reducing waste. In one day, a loom can produce 62 yards of fabric, or about 18,000 yards per year. Huston estimates it takes about 2.25 yards to make a men’s sized shirt. Over the course of a year, the amount of fabric he can produce roughly translates into 8,000 shirts. And that is just from one loom. Imagine the possibility if he is able to actualize one of his long-term goals to cultivate and nurture enough support for local cloth to sustain several operational looms, running at full capacity. Presently, running one loom full-time results in production higher than demand.

As we delve deeper into what a local textile system looks like, continually building and adding elements to our own Northern California Fibershed, it has become clear that a few crucial puzzle pieces are missing. How can someone without space for a loom nor the talent and patience of a weaver participate in local clothing? How can we as consumers make use of the hard work of local farmers who raise sheep, goats, and alpacas, and turn fiber into yarn and cloth? Drawing inspiration from the well-established community supported agriculture (CSA) model, which funds food producers for a season in advance, Fibershed has introduced the Community Supported Cloth Project, a way to actively participate in supporting our regional economy by pre-purchasing elements of the cloth straight from The Farmer, The Spinner, and The Weaver.

With the Mendocino Wool and Fiber Mill slated to be operational soon, the existence of Huston Textile could not be more critical. Both Fibershed and the Mendocino mill have been working with Lani Estill – the sheep rancher of Bare Ranch – to develop a yarn fine enough and strong enough to be used in Huston’s machinery. Estill and family raises their sheep using ranching practices, called Carbon Farming, that not only reduce greenhouse gases, but regenerate the soil itself, which helps draw down additional levels of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The resulting fiber and fabric is thus Climate Beneficial Wool. The goal of Fibershed’s Community Supported Cloth Project is to highlight the opportunities within our community by weaving a run of 500 yards of cloth from wool that was raised and woven locally — and when Gilbert’s mill is running, it will be spun locally as well.

Community Supported Cloth pre-sale reservations went up for sale to the public at the 2016 Wool and Fine Fiber Symposium on November 19th, 2016 at Point Reyes Station, and reservations for the cloth can be placed thereafter with Lani Estill directly on her website, www.lanislana.com.

The reintroduction of a mid-tier supplier into our apparel chain holds the potential to shape how the industry will adjust and adapt, like a meandering river shifting course in rhythm within its ecosystem. All Huston knows is that “the more I source locally, the more other people can source locally.” And that is a good thing.

Valerie Yep is a maker, crafter, spinner, knitter, sewer, urban famer, and general doer. A California native, she is inspired by the trees, the mountains, the beach, and the way the earth smells just after it rains. You can follow her creative endeavors on Instagram and Ravelry under @vyep.