Written by Sarah Lillegard & Photographed by Paige Green

At Valley Oak Wool Mill, the day starts early with hopes of beating the summer heat. Despite the morning hour, the mill’s owner and sole employee, Marcail McWilliams, is brightly moving between the buildings checking machines and running through a mental list of what there is and what is to come. The mill itself is housed in two buildings that sit on a portion of 20 acres in Woodland, CA. As one of the few mills in the fibershed of Northern California, its unpresuming exterior encases a history that extends from the spinning frame that was built in 1940 to the skeins of yarn that were finished this very week. The mill is a living line running from the producer to the product, and from the past of small-scale wool production to its future.

Those lines of history are not just in the machines, but in the mill itself. Valley Oak Wool Mill is the second life of Yolo Wool Mill. Jane Deamer first opened Yolo Wool Mill in 1989. Prior to the mill, Jane had a wool scouring co-op in Winters, CA, which she started to help process wool from her sheep. In building the co-op and then the mill, Jane launched a legacy of creating resources for regional woolgrowers. Marcail unknowingly stepped into that legacy when she began working at the Yolo Wool Mill in the fall of 2009.

Marcail’s interest in fiber and textiles was sparked when she was seven-years-old by learning to knit with her grandmother. Finding the process frustrating, Marcail didn’t pick up knitting again until she was in high school. While attending college at California College of the Arts, Marcail was introduced to weaving and pursued it through studying abroad in Japan and earning a degree in textiles. After graduating and coming back to her home community, a friend recommended checking out the mill. Marcail remembered touring Yolo Wool Mill as a child with her Girl Scout troop, and after seeing it again, asked Jane if they had an internship available. Jane instead offered her a paid position and Marcail began a seven year stretch working at and learning from the mill.

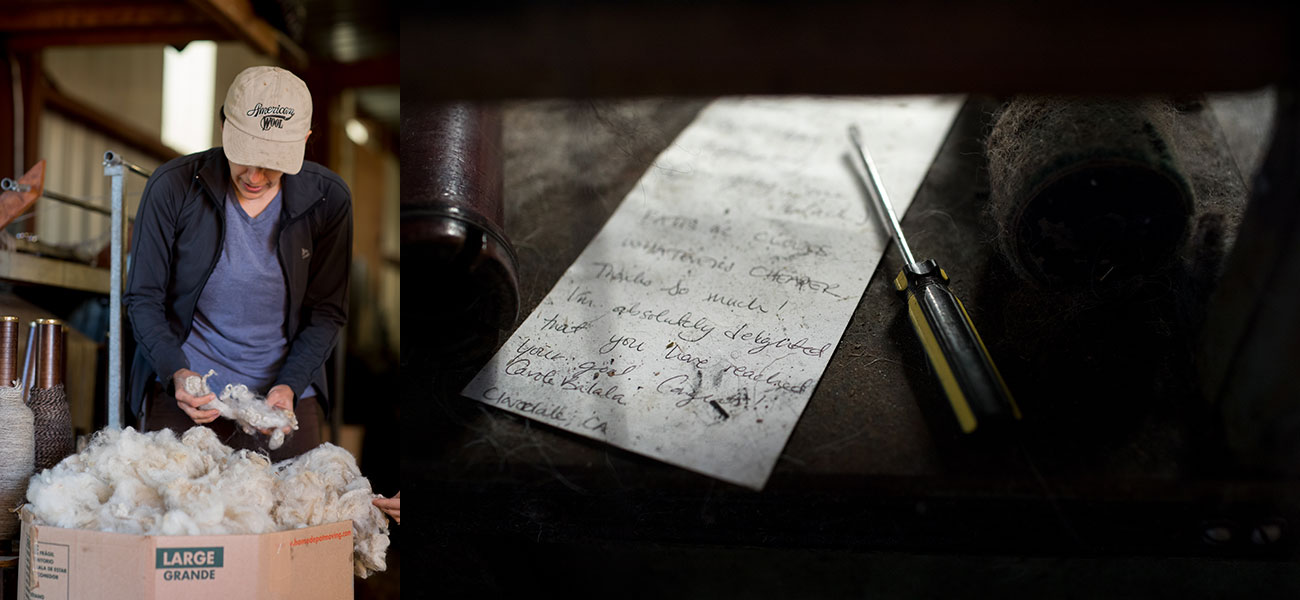

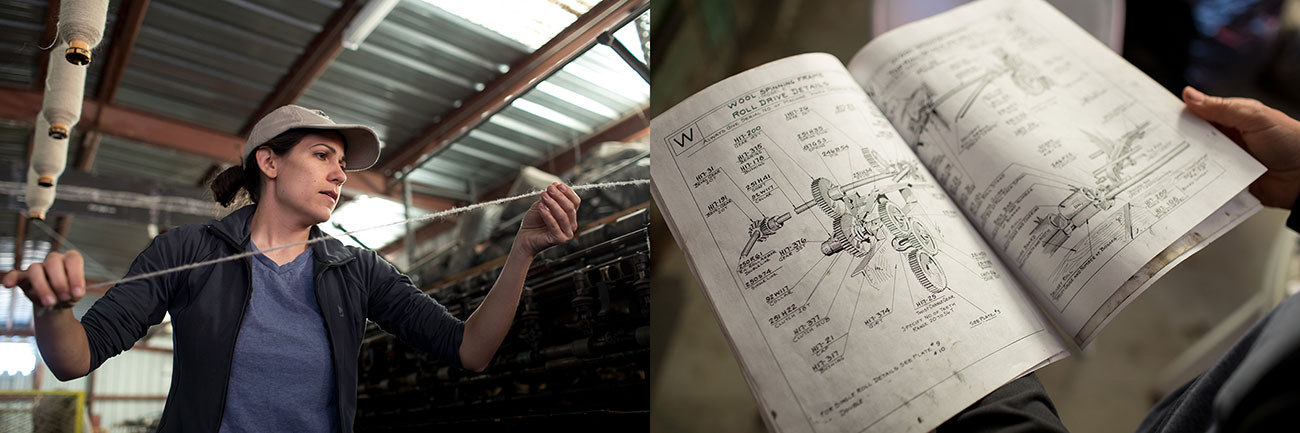

At the beginning, Marcail recalls hearing people’s perceptions that millwork was just factory work with comments like: “I thought people went to college so they didn’t have to work in a place like this.” While that may be the case for large mills with multiple employees doing single tasks repeatedly, it wasn’t so at Yolo Wool Mill. Says Marcail of her time there, “little by little you’d pick up other skills” as the job shifted between different machines, doing customized work. Now that it’s Valley Oak Wool Mill and a one-woman operation, Marcail is hardly in a monotonous factory setting. Her customers have been a steady flow since reopening the mill in November of 2017. They are a combination of new and returning livestock producers who own small flocks mostly around Napa, Sonoma, and Petaluma. With half of them new to processing, Marcail is not only running the mill but also helping educate producers about wool production. The days can fluctuate between answering customers’ questions, managing workflow, billing, and doing machine maintenance. There is work to be done, so she does the work. But it’s more than just that. Marcail’s passionate investment in the fiber, the mill, and the many people who now look to her to process wool, are revealed in the anecdotes she shares about flock owners and the way she seems to recognize each fleece. “I knew inside me that I could do it because I had been doing it, from working here. But nobody works in a mill and then starts one. Everyone else that I know of who has started a mill has no milling experience. And that’s common. So why would anyone do this? … It’s the customers thanking me.”

Looking at wool processing step-by-step, Marcail’s eye for detail and consideration for the final product become as critical as the machines themselves. When wool is brought to the mill, the first step is scouring. Marcail skirts as she feeds the wool into the washing machine, pulling out short pieces (second cuts), vegetable matter (VM), greasy tips, and matted areas from the fleeces. Even if a fleece has been skirted during the shearing, she still checks it prior to scouring. The extra check can prevent problems further down the line.

The scouring takes place in an industrial washing machine, whose previous life was washing carpets at a laundrymat. Instead of adding a detergent, Marcail uses Jane’s recipe of soda ash and surfactant, which when combined with the lanolin makes soap. As she describes it, “The products aren’t a soap on their own. It’s kind of like old-fashioned soap making. All of the ingredients inside the washing machine make it.” The process includes two wash cycles, a rinse and a vinegar cycle. The vinegar helps bring the pH of the fiber up preventing it from becoming brittle from the scouring. The wool is then put through a spin cycle and laid out to air dry.

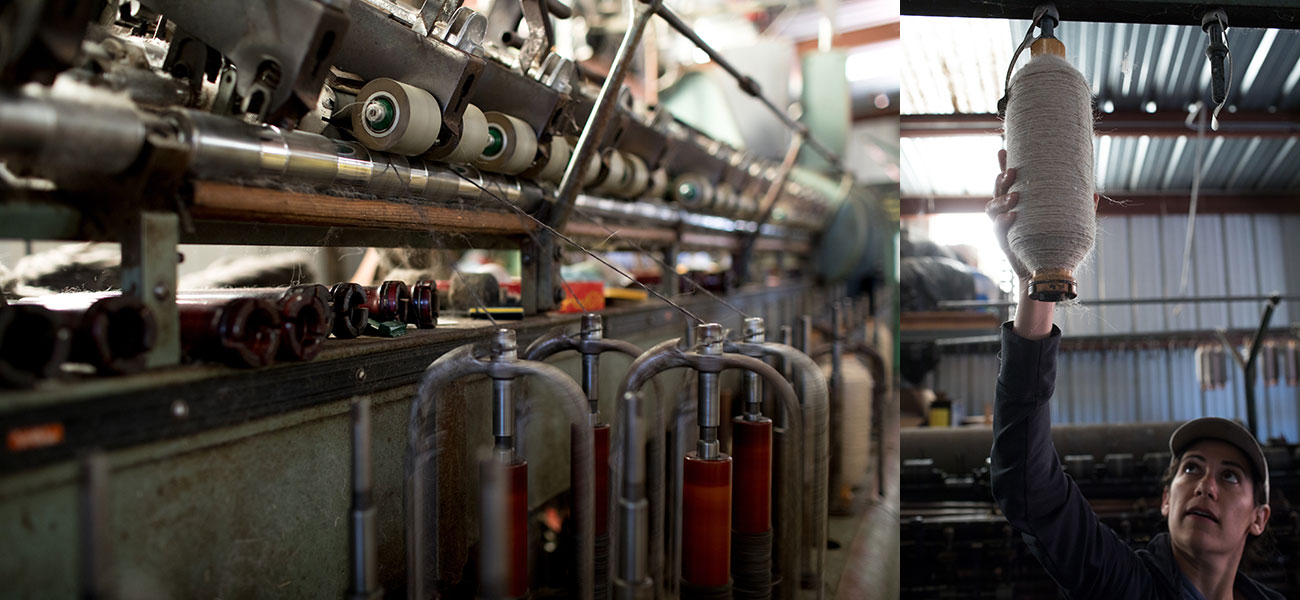

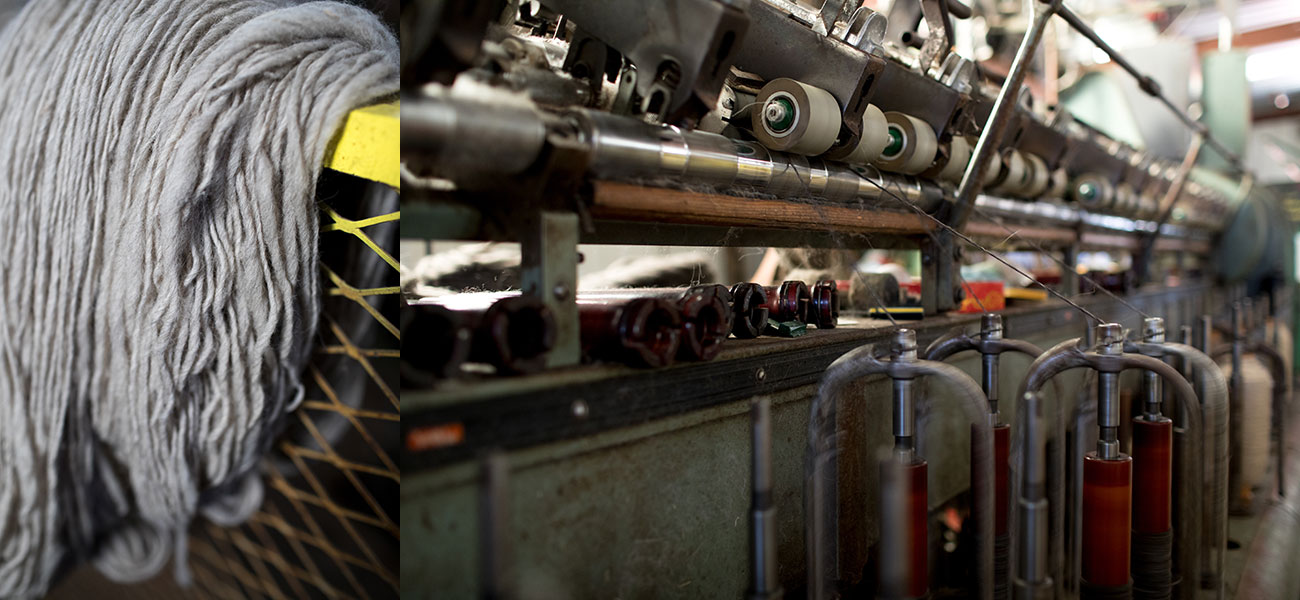

After the scouring and drying, the wool is carried across the driveway to a second building that houses the carder, roving frame, and spinning frame. Together they fill the building with a steadfast presence and even though they are all housed inside, weather determines their productivity. If it’s too hot, then the space is unbearable. If it’s too windy, then the wool is unruly in the carder. Humidity is also a concern. And so, like the flock owners who supply the wool, Marcail has to keep an eye on the forecast and pivot her days accordingly.

Today the weather is right and so the wool goes through the picker (opening up the wool locks) and then gets fed into the carder’s hopper. Once in the carder, the wool passes through a series of rolls with teeth progressing from coarse to fine. Coming out from the carder can be either sliver (rhymes with diver) or batting. Sliver and roving are often referred to interchangeably, but the sliver is directly off the carder, while roving goes through pin drafting which further controls the thickness of the carded wool.

Across from the carder is the roving frame where barrels of coiled roving wait. Marcail feeds these into the roving frame with a deftness that speaks of her experience working in mills. The roving frame will create a single ply yarn.

Like all steps in the process, a customer can choose for this to be their end product, but most people want a two-ply yarn so the cones are moved to the spinning frame where they are plied together. The yarn is then finished on the skein winder.

With everything in motion the process seems orchestral—each machine doing its job, contributing critical components to the final product. There’s that harmony and then there’s when things break down. Since the machines were made by companies no longer in existence, Marcail emphasizes, “There is no Google. There is no YouTube for this. I have to figure it out.” Sometimes that’s drawing on previous solutions. Sometimes that’s talking to a local mechanic whose closest experience is with agricultural equipment. And sometimes that’s trying to get a hold of another mill to see if they have a similar machine to share information on. Marcail explains how it’s hard to get resources when the mill is small scale. Her infrastructure of support is essentially herself and a slow growing community of other small mill owners. From the outside this seems like the most daunting part: facing problems alone. But Marcail approaches it with the faith that she’ll learn, find or discover what’s needed.

When Marcail first described Jane she called her fearless. The mill is not the only legacy shared between the two of them. It’s the same spirit of fortitude, community building, and that word for Jane: fearless.

If you’re interested in processing through Valley Oak Wool Mill, please visit the website to review their prerequisites. See a short PBS clip about the mill re-opening. Follow along on social media on Instagram @valleyoakwoolmill and on Facebook at Valley Oak Wool & Fiber Mill