One Acre Exchange supports the development of an agricultural economy centering the sustainability of farmers, workers, and the planet. In North Carolina and beyond, we support farmers and artisans in the growth and development of industrial hemp because of its tremendous potential to revitalize local economies and regenerate the environment. In this article, Tyler shares a look at the 2020 harvest, processing, and marketing options.

Written and photographed by Tyler Jenkins

It’s hemp harvest day in the North Carolina Piedmont. Today we are harvesting 5 – 10 acres of this hemp crop for fiber research. Farmer Jeff Griffin has enlisted the help of his neighbor and longtime friend, Gene, to cut down our stand. Gene rolled up in a John Deere with a sickle bar mower. The sickle bar was one of the first types of mechanical mowers, appearing first in the 1840s as a horse-drawn design and gaining more popularity in the late 1860s. While they cut slowly and can be time-consuming and expensive to fix, sickle mowers are time-tested, practical machines with a long life span, good at cutting at angles and over hilly and uneven land. Growing up, many of the farmers around here took their first assignments mowing fields for the family farm with the sickle mower. This implement was purchased and used by Gene’s daddy when Gene was a boy. Our main concern with Gene’s machine was about the blades in the cutting mechanism as it mowed through thick layers of gummy, green hemp stalks.

The mower takes a few passes around the hemp stand, and we notice a few things. First, we spot a couple of areas of clear success. These patches of land sport nearly 7-9ft tall stands of densely growing pinkie-sized stalks of hemp reaching towards the sky. In these spots, we’ve been able to completely shade out any competing plants below. This is what we’d like to see over an entire field. The spots with the best growth will be flagged and prioritized in our hand-harvesting system. A few spots with less full growth held a mix of stray cover crop seed and summer weeds such as pigweed. As expected, areas that were more prone to flooding, pooling, and heavy runoff (ditches) were less successful in producing a dense stand of hemp. Another interesting observation is the firework-like popping from the tops of the plants, oils, and seeds erupting from stems that have already set flower. Watching a grown over field come down like this, staring towards Fall, brings the satisfaction that often comes with a fresh haircut.

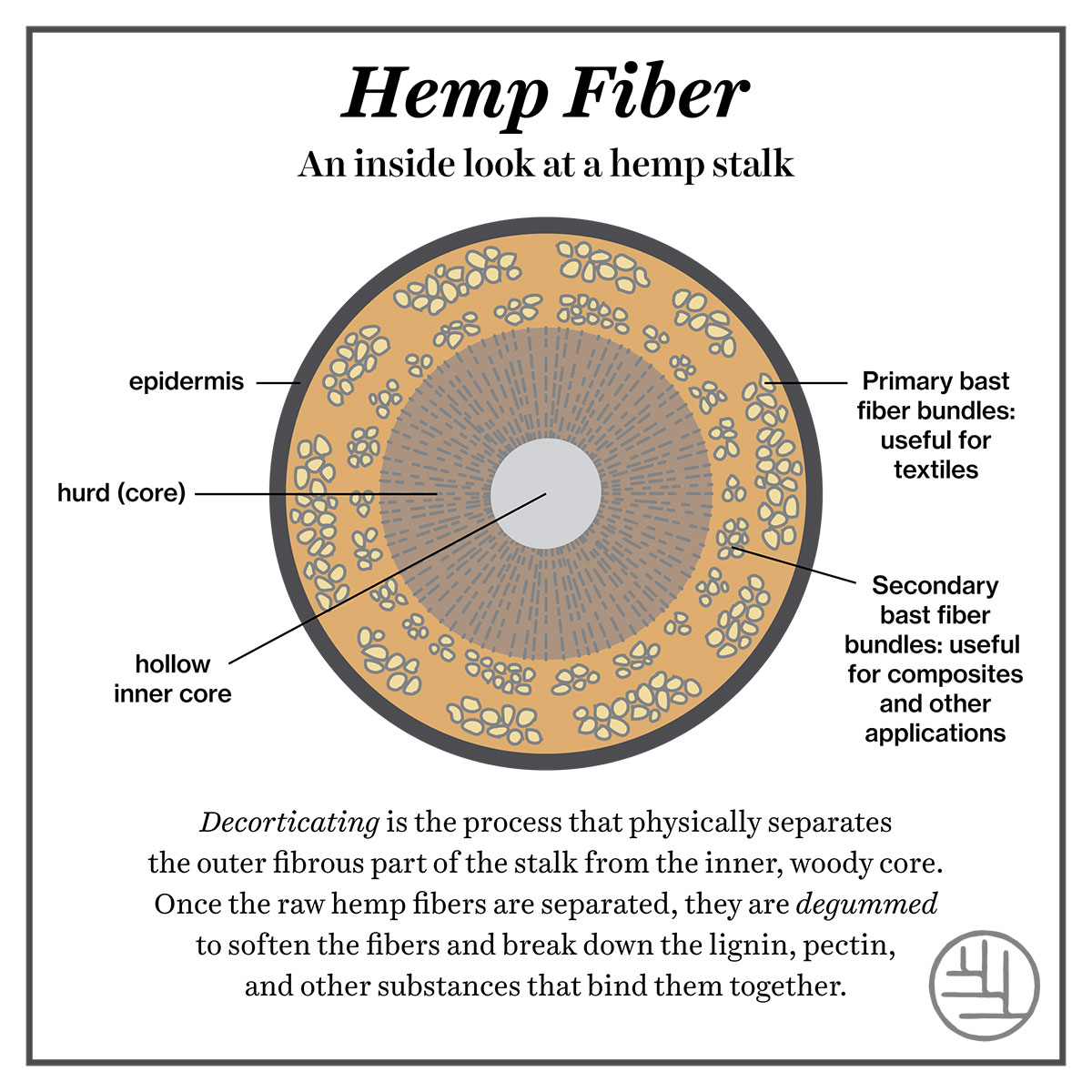

Once 5-10 acres of hemp stalks have been mowed down, they’ll be monitored in the field for the next 3-4 weeks while retting in the field. Retting is the process of facilitating breakdown of pectins connecting the bast fiber to the inner core. Moisture from dew provides the microbial activity for this enzymatic breakdown. Two other methods of retting hemp, water, and chemical, are employed at scale in places throughout the world but are more mechanized and expensive, aside from the environmental costs.

Throughout the next few weeks, we’ll be seeking to learn about the retting process through observation. The goal is to achieve as much breakdown of bast fibers from the woody core as possible, but not let the crop rot (rett) so long that fiber quality starts to deteriorate. To achieve this, we’ll take a look at it daily. Picking up stalks, breaking and peeling them, trying to get a sense of the process as it happens – immersion learning with nature.

In roughly 4 weeks’ time, we’ll employ hand labor to harvest our crop. Once dried, the crop will be set into bundles, end-to-end, and transported to a hub for decortication. Field decortication will also be trialed. We’ll be gathering data on dry weight of stalks and weight of fiber produced from our small decorticator, as well as quality observations from the fiber that comes out of the decortication process. Assuming a successful retting and decortication, our final step will be to run the fiber through two tools of refinement: a scutching machine and an antique horse hair separator. We believe there is a lot of research value in walking through these processes and are eager to explore the processing ins and outs further. While we wait for the crop to be ready for processing and refinement. It seems a good time to do a deep dive on a few challenges to hemp production.

There are some realities that we’ve tried to highlight in this work that should be made more plain. While there are a number of points that could benefit from further exploration, perhaps the two greatest barriers to expansion of the industrial hemp industry are the availability of viable seed and the rigidity of the current regulatory structure in regards to hemp fiber production.

Seed is difficult to find. To acquire seed for this year’s trial, we spoke to dealers from Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, Colorado, Minnesota who, among others, were distributing seed from China, Ukraine, Italy, France, Canada… among others. The range of price of this seed was $10.00 to $35.00 per pound. Seeding rate for a hemp fiber crop is between 35 and 60 lbs per acre. You do the math. Consider a seed stock at $10 per pound at a 55 pound per acre seeding rate would be $550 in seed costs for one acre before the tractor has even been turned on. For reference, the typical total input costs (seed, labor, gas) for a commodity crop come in around $200-$280 per acre, and numbers can climb much greater if more organics are implemented into the system or if the land being worked is a small farm with a more high touch production system. Whatever the input costs for a particular system, a producer certainly needs to know what can be earned for the crop. Considering the current landscape of emerging markets for industrial hemp, this is a big risk.

Our variety information indicates we can expect around 10 tons or 20,000 lbs of total biomass and 2 tons or 4,000 lbs of raw fiber. Learned experience with this crop tells us to cut those numbers in half and start working from there as a baseline, as those numbers work off peak production in places where they have been growing hemp for decades. The best offer that we received for industrial hemp stalk this year was $0.08/lb. If we’re able to hit 10,000 lbs of biomass per acre (much easier said than done), we’d get $800 gross per acre. This is a great price per acre if there is a way to keep production costs in that $200 – $280 range, but keeping in mind, we’re at $550 in seed costs alone.

The other option? Do the decortication and scutching on the farm and go for the higher-priced long fiber further down the supply chain. The best bulk price we received for clean, long-staple hemp fiber this year was $1.00/lb. At 1,000 lbs of projected peak yield, we’d be looking at $1,000 gross per acre. Better for sure, yet considering the extra associated processing costs, hardly exciting. Consider this as the reward for being an early producer adopter in the current regulatory and market landscape.

Seed costs too much and access to it is not guaranteed yet either. Compounding the problem further is the difficulty in saving seed for future production and local adaptability. One reason is the structure of production agreements, and the other is regulatory structure. Plant variety protections (PVPs) are one of three types of intellectual property protections that breeders can obtain for plant varieties. While PVPs are common in the industry, the exotic nature and small available supply of industrial hemp genetics facilitates terms in these plant variety protection agreements that are unworkable. Most do not allow for seed saving at all, even with a licensing fee. Why pay an extremely high price for seed that I (or someone in the business of seed near me) cannot save and acclimate to our climate? How will I know how to predict yield?

Let us assume one gets a source of seed and, either through contractual arrangement or not, have the ability to grow and save it for future use. Any hemp genetics being newly introduced in the United States will expect to take 5-10 years to acclimate to climates and be reliable in terms of yield and predictable variety characteristics, a time that will be “stressful” on the new seed stock. Remember that when cannabis gets stressed, it increases production of cannabinoids. Remember that hemp for fiber is regulated with the same requirements as hemp for cannabinoid molecule production (such as CBD). Even though fiber comes from the hemp stalk and cannabinoid from the hemp flowers, the regulatory framework is overlapping. We planted two varieties of hemp this year, and one has “tested hot” — meaning it has been found to score above the allowable 0.3% THC threshold — and our expectation is that the other variety will as well.

Considering the high costs of hemp seed to even acquire and, further, to adapt and build a seed stock in local growing regions, it becomes difficult to make a case to even grow it right now, except for home and niche markets. We continue to see hemp’s place in farms of the future, yet the barriers are very real. The best way to approach production at this moment may be to start the learning curve for future market opportunities or in small homestead production.

We look in silence over the rolling fields of rural North Carolina, layered with cannabis stalks. Gene and Jeff have been cutting these fields since the Nixon Administration. It’s here, in the fields, where the past and the future take up together to create anew.