Written and photographed by Kara Fleshman

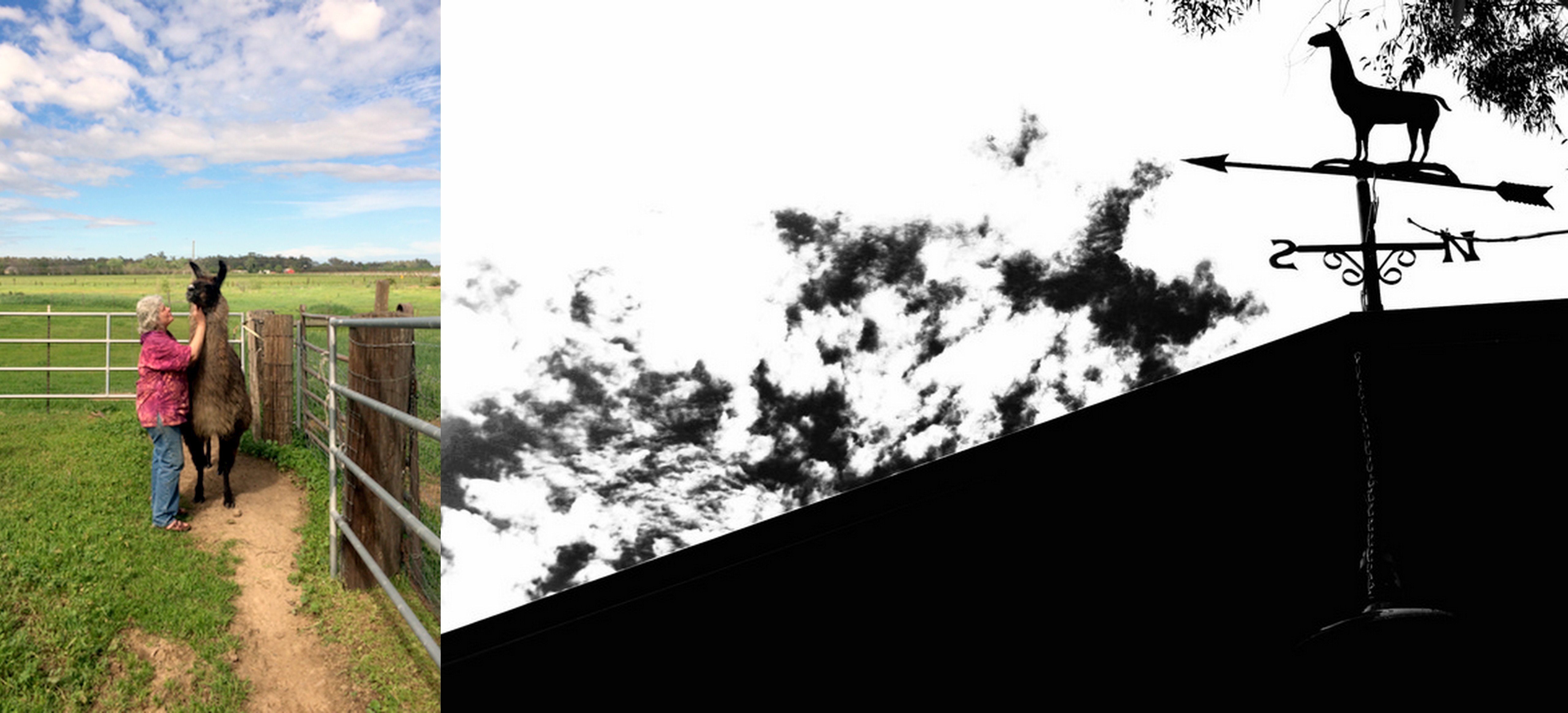

I drove down quiet empty open roads on the outskirts of Vacaville in Solano Country to meet Margaret Drew. I came to write about her Llama ranching business, Stonehenge Llama Ranch, the products she sells, and the methods she uses, but our conversation could not go directly there. It turns out Margaret is one of those people who make it clear within minutes that they are the type of person who is above all else curious, self taught, and capable. The type who subtly encourages questions and can’t help but stretch themselves to look for answers.

First thing, she began showing me her experiments with felting by blending llama hair and sheep’s wool, using different creative techniques to achieve bowls with 3D textures, bags, purses, cases and wall hangings with strong colors from the plants she cultivates outside her back door. We talked about the differences in the properties of sheep’s wool and llama hair as we began wandering back and forth across her property to get a closer look at some of the dye plants she has been raising and learning with.

We looked at the Osage Orange tree whose bark is so strong and decay resistant that it has historically been a natural choice for use as fence posts and rifle stocks. We see one stump popping up in the wrong place that she has been trying to let die and pull out. Nothing seems to be stopping it from continuing to live, even after all of its branches have been chopped and it sits in the ground as a sliced up lonely stump.

We looked at California winged sumac whose green leaves would never hint that it makes a red and yellow dye. We looked at pistachio trees, who happen to have a hull on the outside of the shells most of us are familiar with when we crack them open to eat. This hull is both a mordant and a modifier, it keeps dyes on fabrics so they wont fade or wash away and when added to other dye baths, it “makes colors show where they normally wouldn’t.” She talks about the pistachio’s importance fixing rug dyes in Turkey as we continue to walk toward the next dye plant. The scattering of these plants across her property speaks to the natural way dyeing is often integrated into curious people’s lives, making space for itself to fit in wherever it can.

Margaret allows herself to learn from these plants in those extra moments that open up during full days where she is responsible for taking care of over thirty animals while running two other separate businesses: Stonehenge Graphics and Stonehenge Hospital Inspection. Between explaining the details of her interests in screen printing, graphic design, and managing and carrying out hospital inspections, Margaret begins to educate me about the genealogical history of llamas.

There is a difference, she tells me, between Llamas with two L’s and Lamas with one L. Lamas are a genus of the Camelid family, whose ancestors appeared around 45 million years ago in what is now called North America. Some of these ancestors went north around two to three million years ago and became camels and dromedaries in Asia and North Africa. These animals developed bodies that could withstand harsh climates with inconsistent access to water. Others went south and settled in the cold, high altitudes of the Andean regions of South America where they branched off into the genus ‘Lama’, which includes the domesticated species of Llamas and Alpacas and the wild species of Guanacos and Vicuñas.

Margaret explains that the alpacas were selectively bred by people in the Andean regions on present day Peru to have very fine, soft fibers. The llamas, larger creatures closer to the Guanaco, were bred and utilized not only for their fibers, but also as practical, socialized pack animals. These animals have shorter fibers and more guard hairs. The Camelids in the Lama family we the first domesticated animals in South America prior to European colonization and still maintain a tremendous importance in the region.

While the llama and alpaca have been developed over thousands of years and integrated into Andean life in a practical and compatible way, the Llamas that came to the US made it back to the home of their ancestors in North America in a contrived, awkward way. They were imported as exotic specimens of great interest to those with the money to afford their importation. Suddenly, sometime in the early 1800’s, the biggest and best llamas in South America were herded into stone paddocks where they were kept trapped, awaiting shipment to an island off the coast for quarantine before ending up in North American zoos.

Over time the market has changed in the United States. The thrill of the ‘exotic’ seems to have worn off to a degree and their practicality as resilient resourceful animals has found llamas a place on Margaret’s Vacaville property. She explains that in the US most people who purchase Llamas have the luxury of letting them ‘retire’ or live out their roughly 25 year life span on their owner’s ranch. Although the hair on an older animal might be coarser and their bodies move slower and pack less weight, as Margaret says, “Nobody wants to eat a $20,000 alpaca or llama.”

Margaret came into Llama husbandry in a slightly different way than the zookeepers and exotic animal collectors of the early 19th century. When she moved out to Vacaville from Fairfield she decided to spend her $50 housewarming gift on a lamb. “Little by little, curiosity takes you in many directions.”

Margaret’s curiosity took her into the fiber world, where she joined a spinning group called the Twisted Spinsters. It was there that someone was searching for a home for 2 of their llamas, which Margaret ended up buying at an extremely low price. She knew little to nothing about llamas or how to raise them, so she took it one step at a time, teaching herself. She recalls the day one of her llamas had its first baby. The extent of her coaching through the process was a short phone call to another member of her group. “Is he up? Is he alive? You’re good.”

Twenty-five years later Margaret is still learning, observing, and teaching herself. She says that “Now everyone comes to me to ask questions, even our Vet.” Her careful observation, research, and caring intuition has taught her about the nature of these animals and their unique qualities that make them seem more and more like an essential addition to any animal farming system. They are the perfect fertilizer and the perfect weed control. They will eat just about anything, including the weeds that sheep and goats wont touch, like the much-hated star thistle and bermuda grass that drive farmers in the region crazy.

Llamas, with their 3 chamber stomachs, are incredibly efficient. They will eat the star thistles and fox tails before they go to seed, stopping these weeds from spreading their dangerous seed heads throughout the pasture and continuing to stake claim of the land. They are precise animals that will always return to the same place to poop, so that they separate their waste from their food and are not eating off the same ground where parasites live. They organize their actions, and the babies will follow, organizing their own actions in the same ways their mothers did. And it seems like there is something extra special about this manure. Margaret says where the manure sits weeds won’t grow. For Margaret it is a necessary fertilizer, without too much Nitrogen, which she uses to line the bottom of any hole she digs to plant trees on the property.

The day I went to visit Margaret, as she explained her own history and educated me about the history and details of llamas, she was also hosting a large event. Her barn outside was filled with 20 members of a llama group she is a part of that meets to share information and strategies. After catching only small moments of their conversation, I could tell this llama manure was an important resource that llama farmers are trying to bring attention to and make better use of for the benefits it brings to the land. These individuals had an abundance of knowledge to share and a desire to find ways for their skills and the resources they provide to begin making their way into the ears of those who want to learn more about llamas or incorporate their smooth, drapey fibers into their own projects and work.

The day I went to visit Margaret, as she explained her own history and educated me about the history and details of llamas, she was also hosting a large event. Her barn outside was filled with 20 members of a llama group she is a part of that meets to share information and strategies. After catching only small moments of their conversation, I could tell this llama manure was an important resource that llama farmers are trying to bring attention to and make better use of for the benefits it brings to the land. These individuals had an abundance of knowledge to share and a desire to find ways for their skills and the resources they provide to begin making their way into the ears of those who want to learn more about llamas or incorporate their smooth, drapey fibers into their own projects and work.

It became clear to me by the end of our time together that Margaret is an educator and a caretaker, a person who is always learning new things and has the consistency to see her work through to the end. She spends great care on taking care of her animals and producing high quality fiber, which she washes three times after shearing to make sure the fiber is clean and ready for spinning. To learn more about the fibers and yarns she sells as well as the many other areas of expertise she provides, look up Stonehenge Llama Ranch. As Margaret said, “I educate more than I do anything else.” From her homemade aquaponics system, to fiber farming and natural dying, to managing three businesses, Margaret is a wealth of knowledge worth tapping into and supporting.