What rapidly changing weather conditions mean for our regional fibersheds and how innovative farmers and ranchers are stepping up to the challenges.

The largest scientific expedition in Arctic history took place last year and included 300 scientists from 20 countries. The team spent 400 days taking ice, ocean, and air samples. Lead scientist Markus Rex held a press conference on June 16th, 2021, where he shared an overview of what they observed:

“The expansion of the ice was only about half as large in the summer than decades ago and only about half as thick as 130 years ago. The disappearance of summer sea ice in the Arctic is one of the first landmines in this minefield, one of the tipping points that we set off first when we push warming too far,” said Rex.

Arctic Ice Melt Means Less Rain For Our Fibershed Communities in the Western U.S.

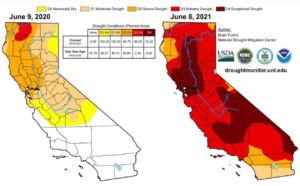

How does Arctic sea ice melting impact our Fibershed communities in California and throughout the Western United States? According to research initially conducted in 2004 by Jacob Sewall and Lisa Sloan (1), Arctic sea ice disappearance has a “substantial impact on water resources in western North America.”

“Where the sea ice is reduced, heat transfer from the ocean warms the atmosphere, resulting in a rising column of relatively warm air,” Sewall said. This warming air blocks the movement of precipitation to our land area and sends storm tracks northward.

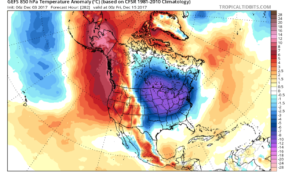

2017 image illustrates what was known as a ‘ridiculously resilient ridge’ a high-pressure system that blocked storm tracks from entering the Western United States for months during the only time of year when precipitation would naturally fall.

2017 image illustrates what was known as a ‘ridiculously resilient ridge’ a high-pressure system that blocked storm tracks from entering the Western United States for months during the only time of year when precipitation would naturally fall.

Climate Change Impacts Are Here Now, And Innovation is Needed

In a recently issued State of the Planet report by the Swedish Academy of Sciences (2), the authors noted that “Climate change impacts are hitting people harder and sooner than envisioned a decade ago. This is especially true for extreme events, like heat waves, droughts, wildfires, extreme precipitation, floods, storms, and variations in their frequency, magnitude, and duration.” (3)

The analysis identifies a particularly damaging and exacerbating force of climate change: “Greater inequality leads to more rapid environmental degradation.” (4) Pointing to a needed transformation of the economic status quo, the authors’ synthesis informs all aspects of our society, from policy to individual lifestyle choices: “Biosphere stewardship involves caring for, looking after, and cultivating a sense of belonging in the biosphere, ranging from people and environments locally to the planet as a whole. Such stewardship is not a top-down approach forced on people, nor solely a bottom-up approach. It is a learning-based process with a clear direction, a clear vision, engaging people to collaborate and innovate across levels and scales as integral parts of the systems they govern.” (5)

The accelerating pace of climate change presents an enormous but not impossible challenge for producers in our local fibershed. Local growers face mounting pressures from changing weather conditions and natural disasters, with two of the most prominent in California and the Western United States being wildfires and drought. Impacts of climate change and natural disasters extend beyond the environmental consequences. There is also a real economic and social toll on communities. Our regional fibersheds are particularly vulnerable in an economic system that favors globalized industrial supply chains over small-scale, regional production. However, our regional producers are poised to be more resilient and dynamic to meet the realities of climate change.

Farmers in Fibershed Communities are Stepping Up to Adapt to the Challenge

The climate circumstances make our producers’ work all that more important and urgent. Fibershed is working directly with farmers and ranchers that are mitigating the effects of climate change through carbon farming practices. Carbon farming practices enhance soil health and increase soil carbon through various land management practices. These techniques work to sequester carbon and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Hedgerow planting at True Grass Farms. Image courtesy of True Grass Farms.

When it comes to drying conditions and drought, in particular, our producers are working to improve soil health, increase soil water holding capacity, and reduce landscape demand for water. This work is necessary in order to restore hydrological cycles and regenerate soil.

We know that poor land management practices, such as intensive tillage, can further diminish soil quality and reduce the land’s ability to absorb and retain water. As a result, soil dries out faster, and less groundwater is replenished. There is an immediate need to scale carbon farming practices on par with the rate at which we see climate change accelerating. Together with our partners, Fibershed is working to support small-scale growers to develop viable and resilient regional production. Three examples of this work in practice include:

- At PT Ranch, 525 acres sit at the base of the Sierra mountains, where melted snowcap hydrates the land. Historically, with the abundance of moisture in the soil, grass has grown plentifully. But with the increasing droughts, the Taylor family needs to be more strategic. For the most part, they have been able to raise about 150 animals, year-round, by managed grazing on the grass alone, along with some feed such as pellets of grain for the poultry. Continue reading how the Taylor family discovered the interconnected benefits of mitigating climate change, producing healthy food, and providing high-quality employment opportunities.

- At Integrity Alpacas, three acres of the property have been designated for work within Fibershed’s Climate Beneficial™ program. These efforts include planting fruitless mulberry trees (which provide shelter, shade, and a food source for the alpacas, along with general carbon sequestration) and bringing the property’s Delta clay soil back to life. Continue reading about Integrity Alpacas plans to ensure the land is better off than where it started.

- At Fortunate Farm, compost application is among several other carbon farming practices that make up the farm’s active Carbon Farm Plan. According to Gowan Batist, farmer and co-owner, partnership with a local brewing company provides the farm with spent barley that is incredible for compost as it is pathogen-free and has a good ratio of carbon to nitrogen. The spent grains are mixed with hardwood chips from local tree trimming companies, then formed into windrows to compost, and finally spread onto crop fields, pasture, and invasive gorse patches (cut down and reseeded with grass seeds). Gowan notes that after covering old invasive gorse patches with compost and reseeding, she has seen many native plant species return voluntarily, such as thimbleberry, salmonberry, elderberry, cascara, and wax myrtle. Continue reading about Fortune Farm’s extensive Carbon Farm Plan.

The benefits of carbon farm practices go beyond adapting to changing conditions. Additional co-benefits of adopting better land management strategies include higher productivity, increased water retention, hydrological function, biodiversity, and resilience. At Fibershed, we are reimaging how we think about the connection between soil, water, and climate change. These practices are essential for the reduction of future climate impacts.

Sources:

- Sewall, J. O., & Sloan, L. C. (2004). Disappearing Arctic Sea Ice Reduces Available Water in the American West. Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 31, L06209, 2004. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2003GL019133.

- Folke, C., Polasky, S., Rockström, J. et al. Our future in the Anthropocene biosphere. Ambio 50, 834–869(2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01544-8

- Downing, A.S., A. Bhowmik, D. Collste, S.E. Cornell, J. Donges, I. Fetzer, T. Häyhä, J. Hinton, et al. 2019. Matching scope, purpose, and uses of planetary boundaries science. Environmental Research Letters 14: 073005.

- Enqvist, J.P., S. West, V.A. Masterson, L.J. Haider, U. Svedin, and M. Tengö. 2018. Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: Linking care, knowledge and agency. Landscape and Urban Planning 179: 17–37., Chaplin-Kramer, R., R.P. Sharp, C. Weil, E.M. Bennett, U. Pascual, K.K. Arkema, K.A. Brauman, B.P. Bryant, et al. 2019. Global modelling of nature’s contributions to people. Science 366: 255–258., Plummer, R., J. Baird, S. Farhad, and S. Witkowski. 2020. How do biosphere stewards actively shape trajectories of social-ecological change? Journal of Environmental Management 261: 110139.

- Tengö, M., R. Hill, P. Malmer, C.M. Raymond, M. Spierenburg, F. Danielsen, T. Elmqvist, and C. Folke. 2017. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond: Lessons learned for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 26–27: 17–25., Clark, W.C., L. van Kerkhoff, L. Lebel, and G. Gallopi. 2016. Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 113: 4570–4578., Nyström, M., J.-B. Jouffray, A. Norström, P.S. Jørgensen, V. Galaz, B.E. Crona, S.R. Carpenter, and C. Folke. 2019. Anatomy and resilience of the global production ecosystem. Nature 575: 98–108.

All images by Paige Green unless otherwise noted.