At the 2021 Fibershed Wool & Fine Fiber Symposium, we were honored to cultivate a program that featured voices from across industries and experiences. The theme of the Symposium was “Weaving Voices: People, Land & Water,” and within that framework, we were able to learn from experienced fiber producers, artisans, agricultural researchers, and workers on the frontlines of some of fast fashion’s most destructive factories and sub-industries.

In hosting conversations between unique textile and agricultural stakeholders, we discovered commonalities in the realities faced by people touched by this industry around the world. We’re inspired by our speakers’ stories and willingness to share their experiences. Follow along below as we share some of our takeaways from the 2021 Wool & Fine Fiber Symposium.

Click here and scroll down for the bio of each Symposium speaker.

Explore our 2021 Symposium Media Page here.

Opening Remarks from Fibershed Executive Director Rebecca Burgess

Fibershed Executive Director Rebecca Burgess launched the Symposium with an introduction to the modern textile landscape. She shared data that reveals the startling inequities within the textile industry and the wealth disparities leading humanity toward an increasingly destructive future:

- It takes four days for a CEO from one of the top five global fashion brands to earn what a Bangladeshi garment worker will earn in her lifetime.

- 42 people now own the same wealth as half of humanity.

- The richest 1% of the world’s population is responsible for more than twice as much carbon pollution as the 3.1 billion people who made up the poorest half of humanity.

- The amount of emissions caused by our consumption (food, electronics, clothing) surpasses any of the other leading direct emissions we generate from living within our communities (transportation, building, energy).

- 25 billion pounds of clothing is sent to landfills every year.

- An estimated 5.6 megatonnes of synthetic microfibers were emitted from apparel washing between 1950 and 2016. Half of that was within the past decade.

- Clothing production doubled between 2000 and 2014.

In order to create a better fiber future, Rebecca said that we must value the creative purpose of every person within the fiber cycle, balance the power within the industry, to establish a dignified textile economy. She specified the need for governments, brands, social entrepreneurs, and impact investors to use their power and money to invest in solutions, which include public and textile (private) sector re-education; vocational training in soil-to-soil systems; and new infrastructure in these systems for manufacturing, distribution, upcycling, recycling, and biodegradation.

“We need each other,” said Rebecca. “We need to work together.”

Watch the full video of Rebecca Burgess’ opening remarks here.

Conversation between Abena Cynthia Agyeibia of Kantamanto Market and Santa Puac of the Garment Worker Center

Santa Puac has worked as a garment worker in Los Angeles for many years, sewing clothing for some of the world’s largest apparel companies. Abena Cynthia Agyeibia makes her living by repairing and re-selling the discarded garments from Western nations at the Kantamanto Market in Accra, Ghana. The garments Abena purchases for re-sale are often the very same pieces garment workers like Santa sew in factories across the world.

Santa Puac introduced herself and her history of working in the garment industry:

“I’ve been at the Garment Worker Center for five years. Like many garment workers, I came here because of injustices and exploitation in the industry. A lot of bosses only care about money. All they care about is how much money a single worker can produce and how fast they can bring in income.”

“A lot of garment workers are mothers with children. They have to work 60-72 hours in the span of 6 days to barely make $250-$300. It’s very hard to make so little money. It’s hard to sustain a family and make ends meet. As a woman, it’s even harder to work in the garment industry because of my kids. When things come up, your boss doesn’t understand. That’s why I joined the Garment Worker Center: to know my rights because it’s not right that people treat us in that way.”

Santa shared images of a garment factory building in Los Angeles, which has poor ventilation and is old. Sewing machines are covered in dust.

Abena Cynthia Agyeibia introduced herself and discussed what it’s been like to buy and sell discarded garments at the Kantamanto Market in Accra, Ghana:

“I sell clothing in Accra, Ghana. I started somewhere before 2013, and it was my big sister that introduced me to the trading business. From that moment, I was selling blouses and shirts for formal office workers. It was dignified work when I started because the quality of the clothing wasn’t as bad. I could sell and make enough money to feed my family. Now, it’s so expensive, the quality is bad, and I’m in a debt cycle. I have no dignity in my job.”

“With my age and my education level, I don’t see myself having the qualifications to do any other job. As a mother, if I decide to leave this job, I cannot feed my family and children. It makes me unhappy, but there’s nothing I can do about it. Because of my debt, even if I can make money, I have to use the money to pay for my debt.”

“The way the structure is built, if you’re entering into the trade for the first time, you may have enough money to buy a bale [of garments]. But you buy it for $75-$250, and then it’s full of trash. You need to sell the clothes at very low prices so people will buy them. They are so bad that sometimes clothing has menstrual stains on them. I’m in debt because I can’t make up the money it cost to buy a bale.”

“Some women don’t have the initial capital to buy a bale. So we borrow money from the banks at 35%. I can’t make back the initial capital it cost to buy a bale, then I still owe the bank the 35%. Over time, the debt keeps building up.”

Kantamanto Market receives about 15 million garments every week, in a region of only 4 million people. Workers have no control over the quality of the clothing, and about 40% of all incoming garments go directly into the waste stream. Kantamanto can’t recycle every garment, so most items end up in gutters around the market which lead to the sea.

Santa and Abena then discussed what it feels like to be on different ends of an exploitative industry:

When asked how it feels to know the garments she’s making often end up in places like Accra, Santa said: “We’re not ones to say the clothes shouldn’t be made. We’re just supposed to go and do our job. A lot of the reason clothes are going over is the result of garment workers producing them, but there’s another force behind it that prevents them from making quality clothing. …I feel anger for Abena, because on my end, I’m supposed to be producing. It makes me feel upset that it’s not even quality stuff. The companies telling us to produce these things know that it’s trash. They’re forcing us to go through this cycle.”

In response, Abena said: “I’m very pleased that you empathize with me. I hope at some point we can find some power to make change. I hope that our groups can empower everybody else for change.”

After this conversation, Abena said the following to Fibershed: “This conversation has made me learn and understand things that I didn’t even know before. I have been in this trade for almost 10 years but had no clue about who makes the garments and what they go through. The garment worker (Santa) is so far away from me, but it’s so sad that we go through the same struggles… I hope more [conversations] like this will happen so things can change and we won’t have to struggle like this anymore.”

You can help fund change! Make direct contributions to the Garment Worker Center in Los Angeles and the OR Foundation’s Secondhand Solidarity Fund to provide debt relief and needed support for retailers and other workers in the secondhand clothing market.

Watch a full video of this conversation here.

Presentation by Anja Lynbaeck of Local Futures

Anja Lynbaeck is Associate Programs Director at Local Futures, an organization that develops, advocates, and connects communities growing ecological economies from the ground up. At the Symposium, Anja discussed the importance of shifting away from a global economy and toward place-based economies.

“What we have today is a de-facto global governance by banks and big corporations that are squeezing our nation-states and influencing our governments across the board to create laws and regulations that favor further globalization and transnational corporations at the expense of people and communities and the planet,” said Anja, who noted that free trade is a “race to the bottom” for people and the planet.

U.S. jobs are disappearing, industrial corporations are receiving subsidies that don’t favor local or sustainable economies, consumption is exploding, and very few products are built to last. While individuals are often blamed or held responsible for fixing these issues, Anja said consumers are groomed to consume irresponsibly through mass marketing.

The real solution? Anja explained that localization is a “solution multiplier.” Policies that shape the economy must be reformed in order to benefit local economies and workers. Community members can help amplify a shift to local by buying local goods and cutting back on unnecessary consumption, while investors can concentrate their capital within their communities.

In order to realize this shift, Anja emphasized the need for community organizing: “If we’re not working together, we end up feeling very disempowered. It’s very easy to get discouraged by the crises going on.”

Watch a full video of this presentation here.

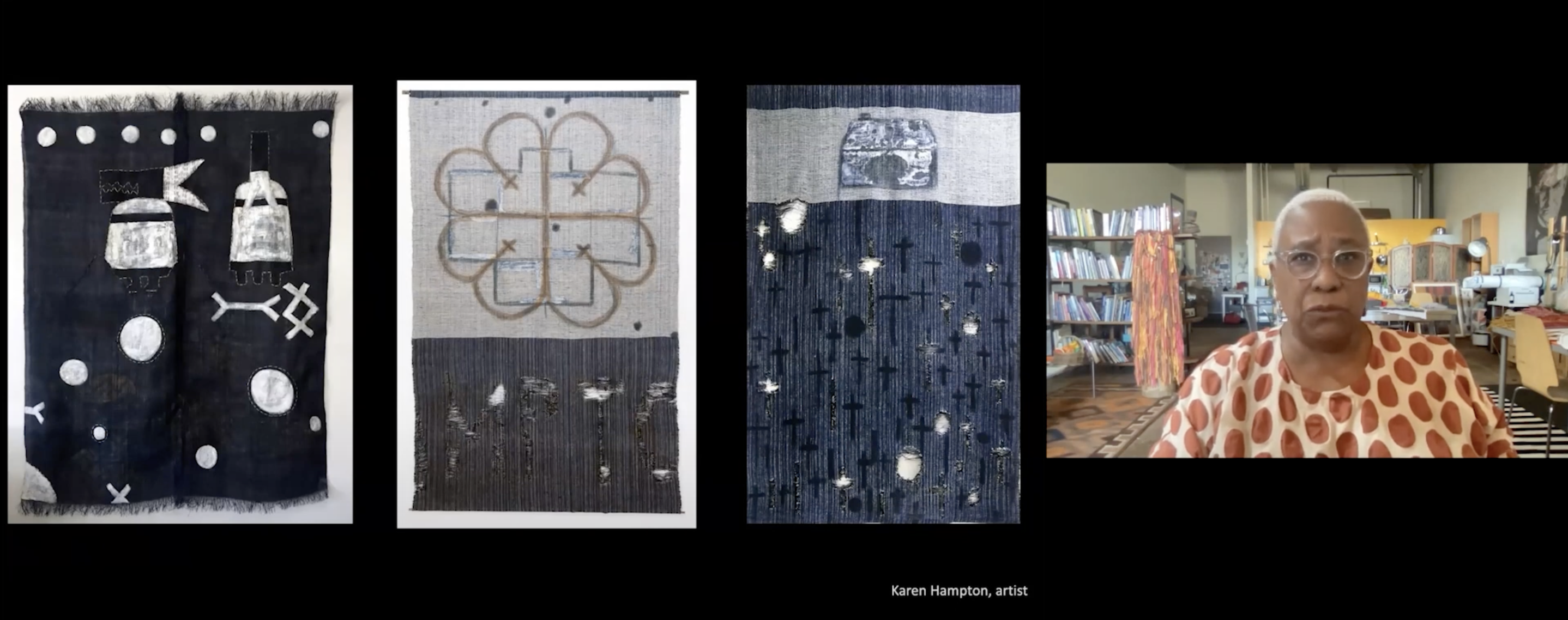

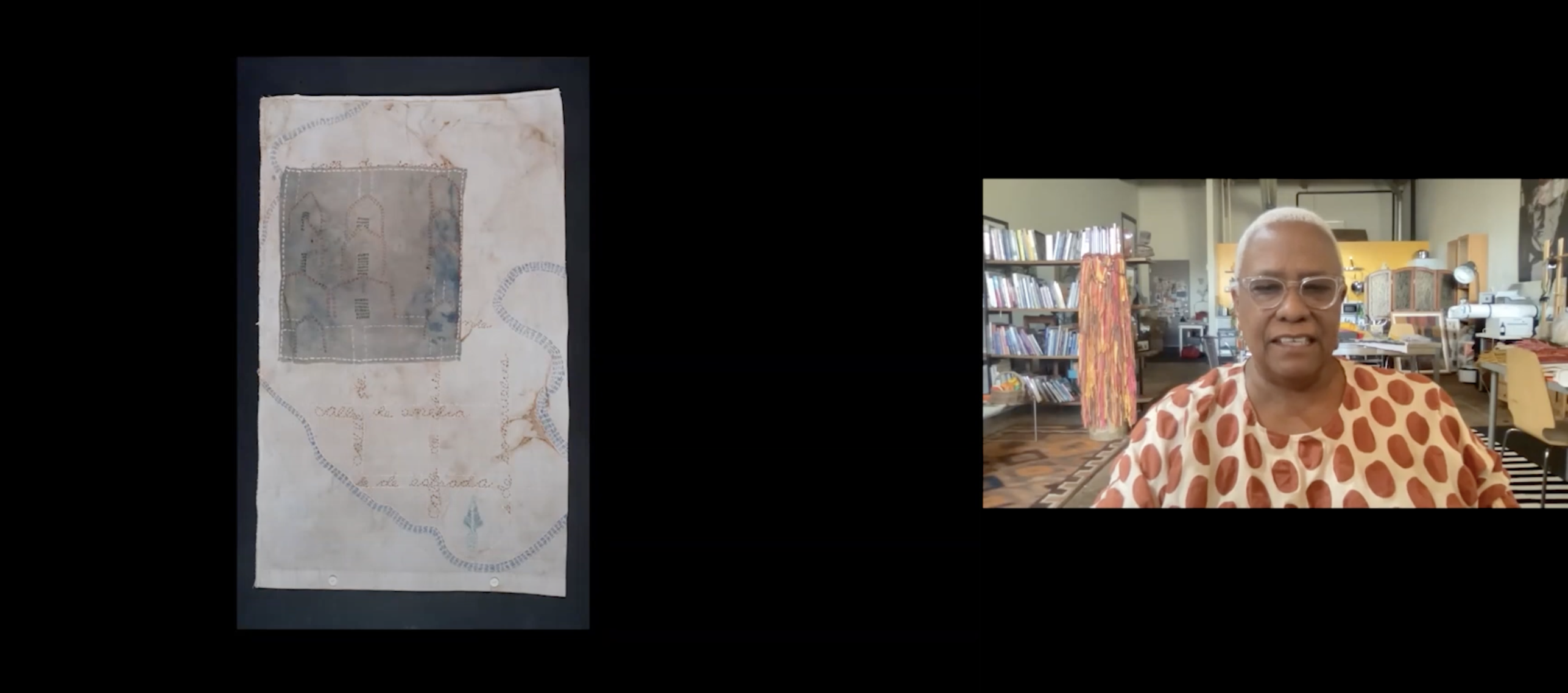

Presentation by Karen Hampton & Conversation between Karen Hampton and Teju Adisa-Farrar

At the Symposium, we enjoyed a presentation by textile artist, anthropologist, and storyteller Karen Hampton, followed by a conversation with Teju Adisa-Farrar. An internationally recognized conceptual artist, Karen Hampton discussed her use of textile as a language that connects history, ancestry, landscapes, and visual art, and some of the influences that have shaped her work. She showed how she integrates the role of a weaver with that of a griot, the storyteller. Teju Adisa-Farrar is a writer and geographer whose work centers on climate and environmental justice, adaptive responses, ecological resilience, and cultural equity.

Karen introduced herself and her work:

“My trajectory as an artist shifted about 30 years ago when I was trying to figure out where I fit into the textile world. I had already been a weaver for about 15 years, and I had met so few African Americans that were connected to weaving.”

“I am a storyteller. I collect stories and have my whole life. Much of my storytelling comes from the fact that my grandma was my primary caregiver who also was Jamaican. That was how I learned about the world, through her stories.”

“I weave and I stitch. I found I had this void of stories from people that look like me in textiles. So I started combining the two parts of me: my training in undergraduate school in art and anthropology. I sought to combine the two things and to find voice in it. I started weaving and telling different stories.”

Karen shared several of her pieces and the inspiration behind them:

“When I was in grad school, I conducted fieldwork, and I visited 11 plantations. When I did that, I was left with the feelings and the visions that I had walking on the grounds. Those were the days when brown and black people were not visiting plantations. The central piece and the piece on the right were both pieces that I created after visiting the Hampton Plantation. The piece on the left I did years later after my travels in Nevada, visiting one of the oldest petroglyph sites and really trying so hard thinking about our environmental degradation and survival as a species. I kept thinking and feeling that we had to go and talk to the ancients.”

“Something I’ve been working on for 20 years now – it was a moment after graduate school where all of a sudden I was given access to my ancestors dating back 200 years. All of a sudden, history became so real for me. This is one of the pieces that came from that.”

“This is one more piece about my Florida work and the story of black and brown communities in northern Florida under the Spanish.”

Teju Adisa-Farrar asked Karen more questions about her work and inspiration. Teju asked Karen why she picked textiles as a medium. Karen responded:

“Textiles were the natural thing. My grandmother had been a seamstress in New York, and my mother, who was an accountant, was happy when she was in the sewing room. As I child, I did anything to get into the sewing room. I was sewing my own wardrobe by the time I was in 9th grade. My ancestors picked me and put me where they wanted me to be to have the opportunity to learn to weave when I was 17. That was the moment when I knew I was going to do that for the rest of my life.”

Teju asked Karen about her experience repurposing textiles. Karen responded:

“I have been into repurposed textiles since the early 80s when I began working on a line of women’s jackets. I was gathering my materials from dumpster diving. I lived in the garment district in San Francisco, and there was so much waste going into their dumpsters. First I was making rag rugs, then I began to develop a line of jackets.”

Teju asked Karen about how her approach to textiles is grounded in the connection to the land and her stories. Karen responded:

“I remember in the early 90s when I was thinking about what I was doing and thinking ‘Is this really what an art practice could be?’ I hadn’t seen anyone else doing what I was doing. I decided that it didn’t matter. If Picasso could have beautiful women as his muse, I could have history as mine. I loved learning more about myself and the cultures of black and brown people. I realized that as I collected stories, it was so healing for me that I knew that if I got that much [out of it], then maybe other people might gather things as well. It was very lonely in that early period, but I just kept doing it.”

“People didn’t quite know what to do with me. It was like ‘Oh, aren’t you supposed to be a quilter?’ I was doing it to heal myself, so I was going to do it no matter what. I knew that it was something that I had to do, there was no question about it.”

Watch a full video of this conversation here.

Agroforestry Panel with Sonja Brodt, Liz Carlisle, Guido Frosini, Jesse Smith; facilitated by Mike Conover

Agroforestry is the practice of integrating trees into our cropping and livestock systems, bringing ecological and economic benefits to farms and ranches. This panel discussed the various types of agroforestry practices, their relevance for California fiber and food systems, and strategies for implementation and establishment. “By having more diversified cropping and livestock systems, we can support the overall resiliency of farms and ranches,” said Fibershed’s Mike Conover. “We can harness the positive biological and ecological interactions between trees and shrubs and other crops or livestock.”

In this session, four panelists from varied backgrounds shared their expertise and experience with agroforestry.

Sonja Brodt, Associate Director of the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program at UC Davis, has focused her work on ecological intensification — designing systems to harness the natural processes that keep agroecosystems functioning and healthy — to address drought and climate change in California.

Following are some quotes pulled from Sonja’s presentation:

“I like agroforestry because it is an approach that increases the perennial aspects of systems, and it diversifies our system. I want to illustrate this with one example here: sheep grazing and vineyards. When you’re growing cover crops in vineyards, you’re already gaining a lot of benefits such as limiting nutrient loss because you have those cover crop roots in the ground, especially during the rainy season. There is more weed control, pest suppression, and habitat for beneficial insects. What my colleague and her students found was that if you add in this whole other element of sheep, you get more benefits. By having sheep grazing during the rainy season, there are even more increases in soil carbon and nitrogen deposition in the soil. The physical structure of the soil improves, and that helps to hold carbon for a long time and also helps to hold nutrients and prevent erosion. There is more microbial diversity in the soil.

“We have been looking at how we can economically intensify native species hedgerows, which are planted along farm edges. There’s already a lot of great research out there that shows that hedgerows planted along crop fields help with carbon sequestration. One of my colleagues did a study of a tomato farm here in Yolo County. They found that the hedgerows could store 18% of the whole farm landscape’s total carbon, even though it occupied only 6% of the land area of the farm. That’s a real plus for climate change. Other studies showed that there was more habitat and food for wildlife, pollinators, and other beneficial insects. In fact, a study in Yolo County showed that hedgerows increased the pollination rate of adjacent canola crops compared to fields in the same area that did not have hedgerows. Tomato fields showed a decreased need for insecticide use when there was a hedgerow present. There’s also water quality protection and run-off prevention.”

Jesse Smith, Director of Land Stewardship at the White Buffalo Land Trust, has been working for the past decade to develop a resilient food economy in California’s Central Coastal region at their 12-acre flagship farm in Summerland, California, and at their newly established 1,000-acre demonstration and teaching ranch near Lompoc, California. White Buffalo Land Trust’s theory of change centers on land stewardship. “Hands in soil, feet on ground.”

Following are some quotes pulled from Jesse’s presentation:

“The integration of annuals and animals and perennials is what I feel is the task of our time.”

“Ultimately what we’re attempting to do is recreate a culture of connection. This is a time in which so many people feel disconnected. What we hope is that people can recognize that we are all connected and we just need to retrain ourselves to see and value those connections as well as to value our role as humans in the forest ecosystem. Not as visitors but as a potential keynote species in its thriving future.”

“One of the projects that we’re really excited to be working on right now is in collaboration with Fibershed. This is a multi-year demonstration plot in the California Central Valley. This project was specifically designed to look at the impact of alley cropping on cotton production. This was a property that had heavily degraded soils and high salt content. We started to ask questions around what the suite of practices should be to start addressing some of the issues of wind erosion, nutrient depletion of soil structure and organic matter, as well as just the carbon sequestration potential of this landscape. We designed an alley cropping system with a focus on white mulberries as a mechanism by which we can bring perennial root systems into this landscape while also providing windbreaks and potential fodder. This is a cycle of compost, cover crops, cotton, and then the final integration of Morus alba.”

Liz Carlisle, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at UC Santa Barbara, has recently been involved in a survey of silvopastures in California: land that is being managed using the deliberate integration of trees and grazing livestock operations.

Following are some quotes pulled from Liz’s presentation:

“We’re looking at just one of these categories of agroforestry: silvopasture. The integration of animals with woody perennials. We’re trying to find all the folks we can in California who are doing this, learn from their systems, and come up with a portrait of what’s going on in California and silvopasture so that we can understand better what some of the opportunities are, but also what some of the barriers are, and how policy or research might help solve some problems for folks.”

“We’ve heard from 21 folks who are currently practicing silvopasture, as well as many, many folks who are interested in getting into it from all over the state. It seems like this is something that’s really on the rise.”

Guido Frosini, of True Grass Farms, is a cow whisperer, land tender, and sylvan protector. He is using regenerative agricultural practices to heal his land with the goal to restore local water cultures.

Following are some quotes pulled from Guido’s presentation:

“I think my generation is now learning alternative ways of coping with what we have been left with. I started my journey 14 years ago. We are located four miles from the Pacific Ocean. Home base is around 120 acres. We currently manage around 1,200 acres, but home base is where we can experiment with different agroforestry practices. The goal is to restore some of the broken water cycles, and that, in turn, helps soil building and nutrient cycling.”

“I think one big shift in agriculture that we might be seeing, I hope so, is a much more collaborative way of looking at solution-based approaches to food production, to community building, to access to land, and to a general restorative communal way of being on this planet.”

“One of the practices we have here is ecological monitoring. When we plant, when we graze, if we rest a field, how do we get the information back? This gives us a sense of how the soil is shifting, how the vegetation is shifting, and how the wildlife population is fitting in within the scenario. What kind of burrows are we finding, and how many predators are there at any given time? It gives you a sense of how healthy a landscape is. Of course, we’re trying to get an understanding of what’s below ground. This is the beauty I think of being a land tender is understanding that relationship of above- and below-ground populations, how healthy they are, and how they express themselves.”

“What I find most fascinating is with the practices implemented, we can increase our waterfall retention by two inches by 2025. We can actually receive more water on this property and hold it within the soil. To me, that is a tremendous feat.”

Watch a full video of this panel here.

Lightning Talks with Marcia Barinaga, John Bailey, Kelli Dunaj, Sarah Keiser

In our Lightning Talks, several of our producer members provided insight into their lives, endeavors, business operations, and land stewardship practices.

Barinaga Ranch, located in coastal Marin County, is home to Marcia Barinaga’s small flock of Corriedale, Romney, and Cormo sheep, as well as some retired East Friesian dairy ewes. On her ranch, Marcia has implemented rotational grazing, a wildlife-friendly pond area, and multiple plantings of Monterey Cypress windrows for carbon sequestration, wind and shade shelter for her sheep. Marcia transitioned from dairy farming to fiber production in 2016 and sells raw fleeces for hand spinners, roving, and a collection of yarns.

Kelli Dunaj of Spring Coyote Ranch raises Navajo-Churro sheep in Marshall, California. “We are passionate about animal husbandry and land stewardship,” Kelli said. “You really have to be obsessed, I think, to keep up with everything, and that fits me perfectly. Life is a constant balance between day-to-day task management (also known as chores) and our long-range goals, which include everything from the genetic diversity in our herd to the color genetics that we’re working with to produce different colors of wool and different styles of sheepskins, to our compost application.” Kelli also serves as Coordinator at the Rainbow Fiber Co-Op, a Diné-led agricultural co-operative established to improve the financial sustainability and equitable market outcomes for the largest flocks of Dibé dits’ozí (Navajo-Churro sheep) remaining on the Navajo Nation.

Sarah Keiser of Wild Oat Hollow, a micro-farm in Sonoma County, uses carbon farming practices on her land. She has a skincare line that makes use of animal fat from her local community as well as a Climate Beneficial line of fiber. “I try to sell a lot of my animals into community grazing cooperatives. Our animals are really handleable. I build community grazing cooperatives all over our county, using hooved animals in collaboration to build fire-safe communities. The vision is public safety and strong, resilient, collaborative communities that take care of each other. As soon as people begin sharing animals in their neighborhoods, they have different relationships to each other, the animals, and to the land.”

John Bailey, Director of the University of California Hopland Research and Extension Center, discussed the Center’s hedgerow demonstration project on their grazing lands. “There are many reasons to install hedgerows,” he said. “There are diverse ecosystem functions that hedgerows support by increasing biodiversity. They also can benefit your livestock operation by forming a physical barrier for wind and providing shelter for your animals. They also improve the soil, increasing the sequestration of soil carbon and reducing erosion.”

Watch a full video of this session here.

Water Systems Panel with Andrew Fisher, Regina Hirsch, Dennis Hutson, Brad Lancaster

Watersheds within our arid and semi-arid landscapes have experienced and will continue to experience changing precipitation patterns with climate change. This Symposium panel discussed rehydration of our land and aquifers and what it means to do this work at multiple scales.

Rebecca Burgess kicked off the session: “For us to have a functioning fibershed, we continue to ask questions about how we can grow the food, fiber, fuel, and flora for the community and how we can continue to be resilient and self-reliant in the face of a changing climate. The first thing we have to address within this changing climate is how we are going to be with water. It is the most fundamental question.”

Dr. Andrew Fisher is the campus lead for the University of California Water Security and Sustainability Research Initiative. He presented on groundwater recharge — the process by which surface water becomes groundwater — and its connection to California droughts. “Enhancing recharge in California really is important,” said Andrew. “We’re pretty much guaranteed to fail in groundwater management if we don’t increase the rate of recharge enormously. This is going to require some risk-taking and innovation, but that’s the way it goes when you try new things.” Andrew has been working with colleagues to find ways to enhance groundwater recharge, in the hopes that their findings could be applied on a larger scale.

Regina Hirsch founded Watershed Progressive, a consulting/contracting firm focused on onsite water best management practices aimed at rehydrating watersheds. “One of the easiest ways for us to add more water to our watersheds and help with the energy nexus is to keep water local where we live,” she said. Regina urged attendees to take small steps: Harvest and make use of rainwater and plant crops that are climate-appropriate. “Where we place our vision of what we want for our communities and our sense of place and where we put those tools together is really important. We can do this.”

Reverend Dr. Dennis Hutson is a retired United Methodist minister and a farmer, founder of TAC Farm in Allensworth, California. Allensworth has an important history as the first farming community founded by African Americans in California. “I believe I was sent here, along with my siblings, to help this community survive and thrive,” he said. Dennis bought 60 acres of land in 2007, where he immediately started looking into how to irrigate the land. His 720-foot well is dwarfed by a neighboring farm’s 2,000-foot wells, highlighting some of the challenges for equity in water access in the region. Alongside his vision of creating opportunities for new farmers within a supportive cooperative, a critical project has been to improve the quality of the water, which has had arsenic levels as high as 160 parts per billion (ppb). (The EPA standard for safety is 10 ppb). ”What we have been able to do is work with U.C. Berkeley, the Gadgil Lab, to remove arsenic from the water, where it is [now] under 2 parts per billion.” TAC Farm is modeling healthy land and water management with a range of practices. “I believe that people need to be more conscious of how water can be used in a more effective way.”

Brad Lancaster runs a permaculture consulting, design, and education business in Tucson, Arizona. “My primary focus is: How can we give back more water to the ecological system in which we live than we take from it? And to achieve this, typically my primary objective is to plant the rain before I plant any vegetation,” said Brad. He focuses on methods of turning rainwater run-off into “run-on,” including rainwater-capturing basins and incorporating more organic matter into soils for better water infiltration.