Written by Ren Lezeu

Innovation deals with generating value through improvement or newness, and comes from the practical implementation of ideas. When applied to the world of textiles and viewed from a sustainability perspective, innovation can mean finding ways to curb the use of synthetic fibers and minimizing the harmful outputs that come from textile production. One such innovative solution comes from Mango Materials, a company operating in Vacaville, California that converts methane — a potent greenhouse gas — into polyhydroxy acid (PHA) polymers that can be used as a substitute for plastics in many different capacities, including as a filament that can fill the role of many petroleum-based fibers without the dangerous environmental impacts. In two recent interviews, I spoke with Mango Materials’ Chief Operating Officer, Anne Schauer-Gimenez, and three students from the California College of the Arts (CCA) to get a better understanding of how old and new technologies are coming together to create an innovative approach to address our textile needs. But first, let’s take a look at what PHAs are and how Mango Materials goes about making them.

PHAs are a family of biopolyesters that can be produced naturally by bacteria and other life forms during their natural life cycle. Mango Materials works with special bacteria called methanotrophs at their facility and feeds them methane. Once the bacteria have lived out their lifespan and have consumed their fill of methane, the resulting material is harvested, turned into powder, and then pressed into pellets that can be used to make various items. During our interview, Anne showed me a backscratcher made from the material and happily explained that if her backscratcher broke, there are bacteria that live in the soil, oceans, and landfills that would actually think of it as food! Those bacteria would eat the backscratcher and biodegrade it back to methane. Because the final output from the biodegradation process is methane, that means Mango Materials can capture that methane and start the process all over again. And, unlike petroleum-based plastics, this closed-loop, cradle-to-cradle recycling process can happen within a span of weeks to months, making it a rapidly renewable resource.

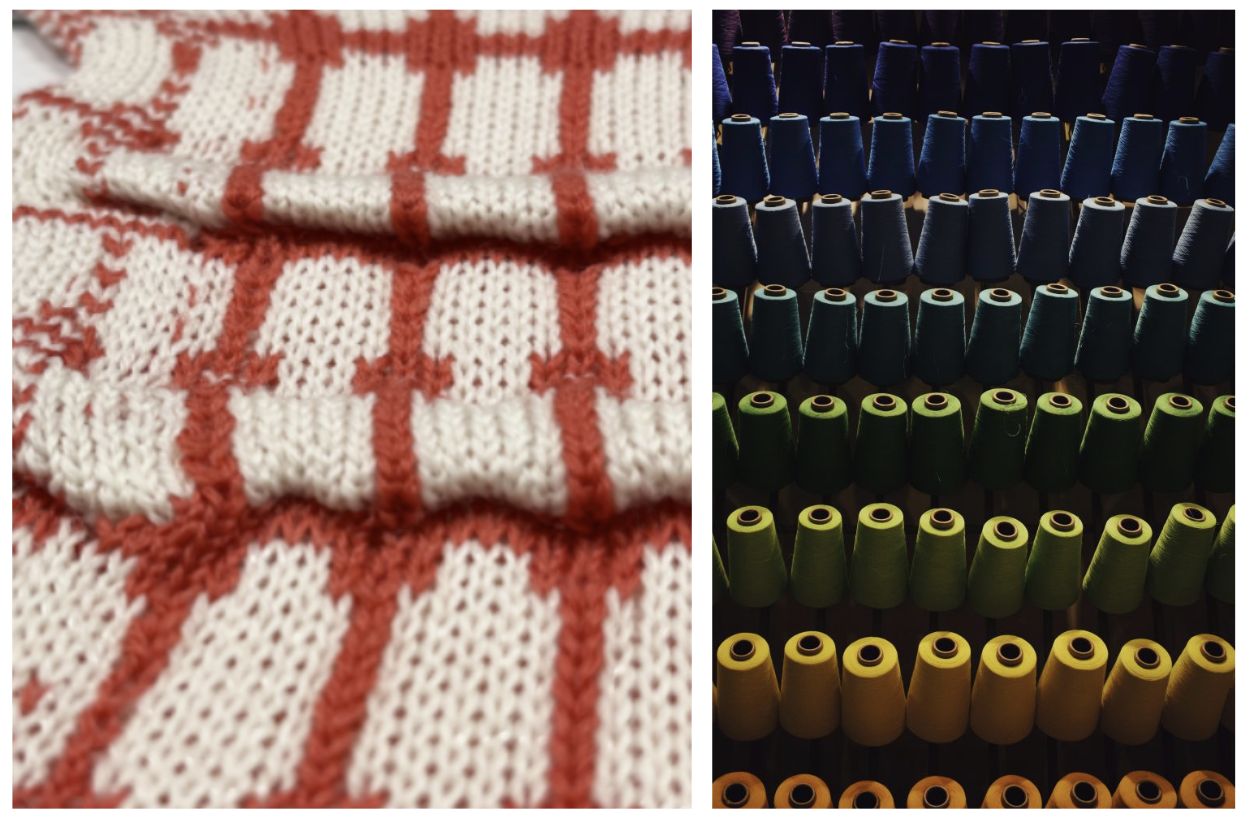

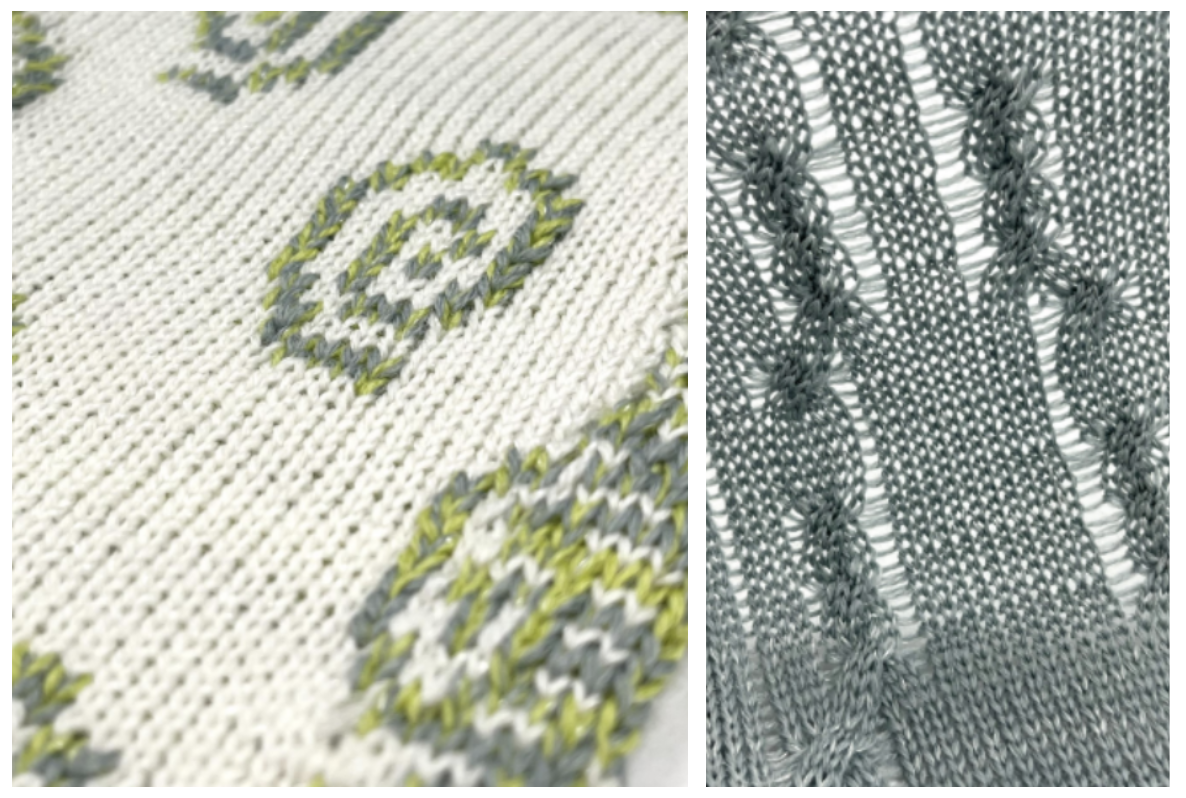

When I asked Anne about the possibility of using PHAs in textiles, she said she could absolutely imagine the filaments being blended with other natural fibers, since the filaments on their own are a bit brittle. Three students at CCA — Jeilyn Mendoza Martin, Maeve O’Callahan, and Ashley Robles-Rosgado — are doing just that. I spoke with the students about their innovative work, curious to know how they had come up with the idea to use Mango Materials’ filament in the first place. The students explained that Mango Materials came to their class to give a presentation, which got them thinking about how the filament could be made stronger and thus able to hold up to being knit on a flat-bed knitting machine.

“We hadn’t met with Rebecca yet to talk about combining the filament with wool,” said Maeve, “so I was thinking about combining it with cotton, but wool addresses the sequestering of carbon in the soil.” And herein lies the true innovation of the students’ work. “In our everyday classes, we’re always talking about sustainability and ways that we can think of a more sustainable way of design that would contrast what has been done in the past in the industry,” said Ashley. “I started getting really involved with the mix of nature and science working together,” added Jeilyn, which led to the students experimenting with combining Fibershed wool with the PHA filaments to see what would work. In the end, they found the two materials to be a perfect pair. “They feel so right together,” said Maeve, speaking not only of the qualities of the knitted samples but of the greenhouse gas-sequestering potentials of both fibers. While mindful wool production can sink carbon into the ground, Mango Materials’ PHAs are fed methane pulled from the air.

Curious to know how this textile might fit into my own wardrobe, I asked the students what the material feels like. The students noted that the PHA filament is soft and has a shimmer or lustre to it, and when combined with wool can be a gateway to showing people that sustainability can be chic. People aren’t going to stop buying clothes anytime soon, so the students placed great value on combatting the stigma around sustainable fashion as being plain and limiting. “These garments can be useful and beautiful,” said Jeilyn, “and can be loved for a long time. At the end of their life cycle, they will decompose and feed back into the environment where they came from, which would be a really beautiful story to tell.” Paired with the wool from a local Fibershed farmer, that story becomes even more personal and can help ground the garment in both time and place.

When hearing about the CCA students’ work with Mango Materials’ filaments, Anne was all smiles. “I love that blending aspect,” she said, “because we’re still in the development phase. Would I love a material that runs off a traditional polyester line at their speeds with their tenacities? Yes, absolutely. Are we there? No.” Blending an already-abundant fiber source with Mango Materials’ filaments means that companies looking to implement a more sustainable fiber into their textile products could have access to Mango Materials’ filaments sooner than later. If producers were willing to give the PHA filaments a go as a blend first, then it would mean Mango Materials could gain some much-needed, large-scale feedback to continue improving. Anne was also realistic about the limitations of PHAs as a material, stating how it might not always be the right material for the job. “I think our material could be part of a portfolio of natural materials,” she said, which could be said about any material.

Finally, Anne and I spoke about the extremely limited textile infrastructure remaining in the US as well as the diminishing presence of textile programs at the collegiate level where information could be shared and knowledge passed down. We talked about the loss of the textile program at the University of California, Davis back in 2018 and all of the opportunities that came with that program to conduct research and innovate. When I asked the CCA students what they would like to say to policy makers and the textile industry as a whole, Ashley said, “I would ask them to consider how expensive not using these alternatives will be for everyone.” For Jeilyn, more responsibility on behalf of the producer was something she felt policy makers should push for. For me personally, I would encourage policy makers to scrutinize their beliefs about natural textiles and their place in California’s production landscape. Petroleum-based textiles have simply had more time and money to leverage in their climb to the top of textile production, but given the same resources, I have no doubt that natural textiles both old and new can do the same.

About the Author

Ren Lezeu is a freelance writer based out of Sacramento, CA, where she lives with her spouse and three cats. She holds a Master’s Degree in Rhetoric from Sacramento State University, where her focus on fiber art, sustainability, and community-building have fed a lifelong passion for writing. She spends her free time exploring California, knitting, and spinning wool