Written by Veronica Kassatly

In my last post for Fibershed, we talked about fashion’s purported commitment to the UN SDGs; about how those are underpinned by the Brundtland report’s definition of sustainability; and about how and why ‘sustainable’ fashion is not actually sustainable at all. The role that different fibers play in offering those who produce them the freedom and opportunity to live the lives that they value, is not even considered, let alone evaluated. Sustainability and environmental impact are simply conflated, with harmful outcomes for all communities reliant on farmed fibers, not just in the global south, but also in the global north.

In this piece, we are going to look at one example of the harmful impact of partial and misleading sustainability claims in the global north. It relates to wool; it provides pointers for the sustainability conversation around all farmed fibers; and it concerns the Navajo.

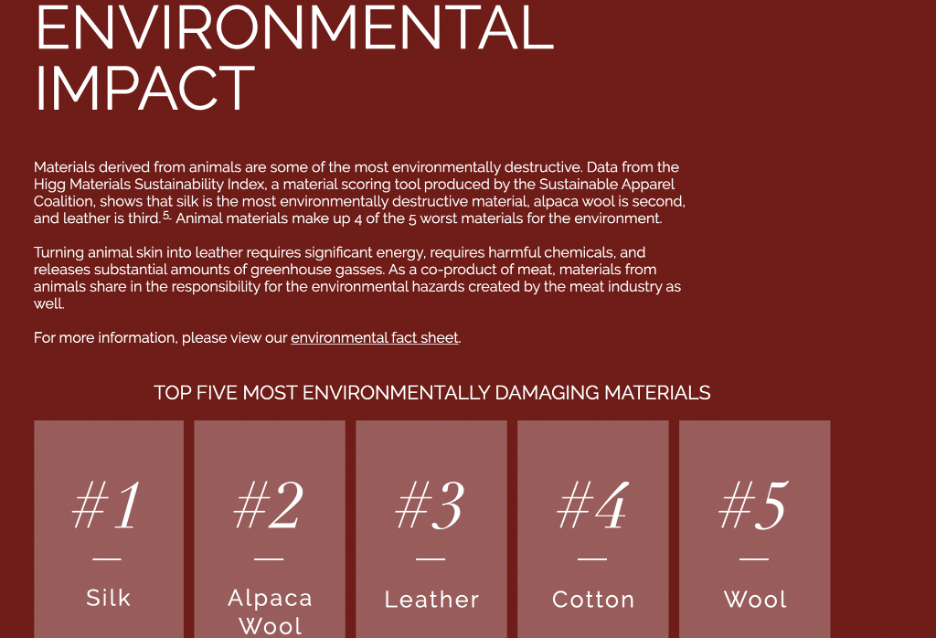

Wool, as the Material Innovation Institute (MII) puts it, is one of the world’s “TOP FIVE MOST ENVIRONMENTALLY DAMAGING MATERIALS.”

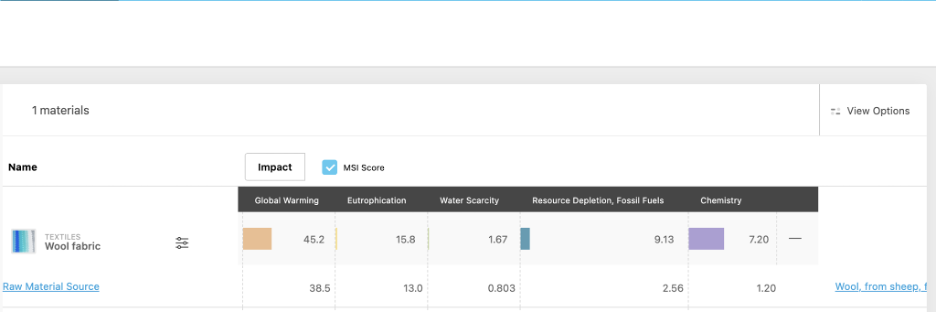

The MII is at least candid about its aims to destroy the livelihoods of fiber farming communities. It is advancing a vegan manifesto, combined with attractive investment propositions for fiber innovators. The MII bases its ‘sustainability’ claims on the Sustainable Apparel Coalition’s (SAC) Higg MSI, and according to the MSI (which conflates sustainability with environmental impact and doesn’t measure socio-economic or cultural impact at all) wool is unsustainable, with a total average impact per kilo of generic fabric of 79 – or more than double the purported average impact of generic, global, polyester fabric, which is supposedly only 36.2/kilo.

But it is not just the MSI that makes that sort of claim for wool’s alleged harmful impact.

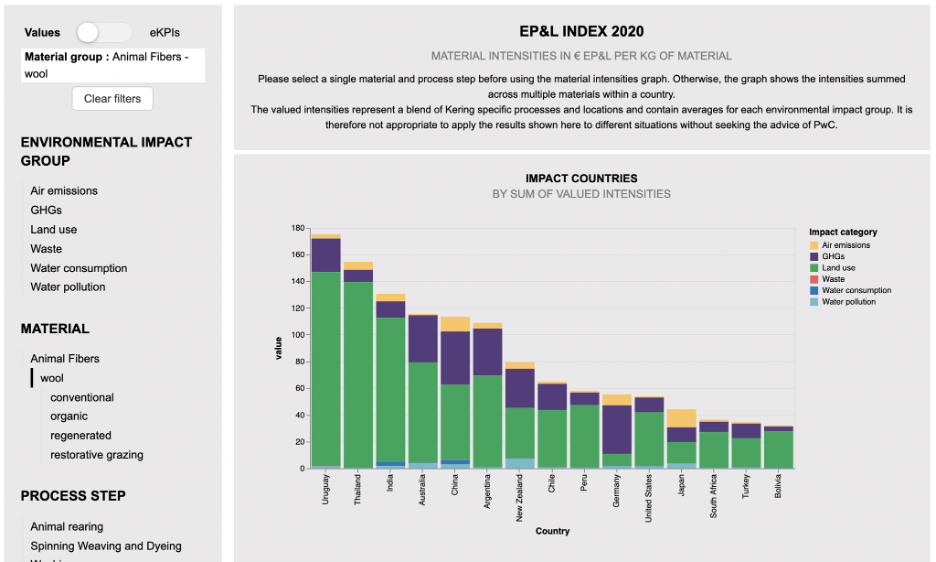

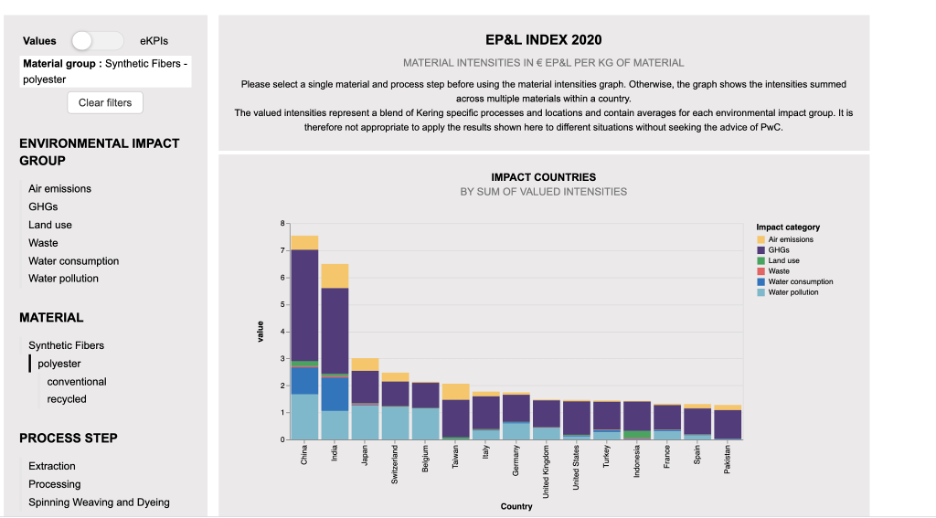

Luxury group Kering asserts that their business strategy has been aligned with the SDGs since 2017, and “includes science-based targets.” We are not allowed to see the science behind the Kering Environmental Profit and Loss (EP&L) – which according to them, is: “a key enabler of a sustainable business model” and “a tool for the greater good” – but it is clear that Kering’s ‘sustainability’ is no more aligned with the SDGs than the MSI’s. Fiber impact in promoting global human development is not only not given absolute priority, it is not even considered. Worse, just like the MSI, Kering’s EP&L assigns extremely unfavourable impact scores to fibers produced by farming communities – many of whom are historically disadvantaged to begin with – destroying their markets, their incomes, and even their cultures, in the process.

For a fiber that can be harvested annually, as an inevitable byproduct of the meat and dairy industries, wool, as sourced by Kering in 2020, allegedly had an astonishing environmental cost. This ranged from €173/kilo for wool from Uruguay, to €31/kilo for Bolivia. Kering’s polyester purchases on the other hand – much doubtless derived from fracked feedstock – apparently came at negligible environmental cost: a mere €1 per kilo for polyester sourced from Pakistan, and €7.5 per kilo for polyester sourced from China.

Clearly, any brand that has adopted either the Higg MSI or Kering’s EP&L as a guide, is – in the name of sustainability – currently attempting to replace wool with plastics. Indeed, some 60% of Kering’s revenue is generated by Gucci, whilst a sweep of Gucci’s Spring/Summer 2021 online collection by Changing Markets found that despite being a ‘luxury’ brand, 32% of Gucci’s offering contained cheap plastic fibers such as polyester.

So much for the benefits to corporations of labeling wool ‘unsustainable’ – it enables them to substitute low-cost fibers for wool in the name of sustainability. But at what human cost?

There has been a lot of dialogue in sustainable fashion about the knowledge of Indigenous peoples – indeed Vogue Business asks us to recognize and reflect on the fact that circularity has defined the way of life of Indigenous communities for much of history. Despite fashion’s caring messages, however, neither respect for Indigenous cultures, nor concern for the past atrocities that they have suffered, actually make their way into fiber and fabric sustainability claims.

As demonstrated in my previous Fibershed article, and further demonstrated here, sustainability as defined and measured in fashion, is currently an elitist, even imperialistic concept in which the interests and cultural values of western consumers and activists define the conversation. For all Indigenous communities, cultural preservation is a critical priority, but this vital aspect of sustainability is never mentioned in fashion.

The Navajo people call themselves Diné, literally meaning “The People.” In Diné creation myths, sheep were put on earth before people and then gifted to the Navajo by celestial beings.

To quote “A Short History on Navajo-Churro Sheep” by Diné be’iiná:

Diné philosophy, spirituality, and sheep are intertwined like wool in the strongest weaving.

Sheep symbolize the Good Life, living in harmony and balance on the land. Before they acquired domesticated sheep on this continent, Diné held the “Idea of Sheep” in their collective memory for thousands of years. While wild mountain sheep provided meat and the Diné gathered wool from the shedding places, that species of sheep in North America did not have herding behavior that permits domestication. As a result, the Diné asked their Holy People to send them a sheep that would live with them and with care provide a sustainable living.”

To quote Robert Moor, “On Trails”

“For centuries, that gift has shaped Navajo culture, just as water sculpts a canyon. Navajos’ internal clocks were set to the daily schedule of herding, and their calendars were structured by the seasonal migration. The introduction of wool radically altered their material culture, by providing the means to weave lightweight clothing, warm blankets, and intricate rugs. Their architecture was fortified by the need to protect sheep from raiders. Pastoralism altered their diet, their relationship to the landscape, and perhaps even their metaphysics. One Navajo woman told the author Christopher Phillips that herding sheep informed her understanding of the sacred Navajo principle of hózhó, or harmony. “The sheep care for us, provide for us, and we do the same for them. This contributes to hózhó. Before I tend my sheep each day, I pray to the Holy People, and give thanks to them for the sheep and how they help make my life more harmonious.”

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Navajo were wealthy and successful pastoralists, with orchards, irrigated fields, and large herds of livestock. The latter were primarily Churra-type sheep, now called Navajo-Churro sheep, originally obtained by raids and by trading with Spanish colonizers. In 1846, with the encroachment of American settlers on Navajo lands, that way of life was brutally disrupted. Kit Carson’s militia viciously terrorized the Navajo, burning orchards, destroying crops, and killing sheep, culminating in The Long Walk of 1864-1866 during which nearly 10,000 Navajo people were forced to march on foot more than 300 miles to an American internment camp at Fort Sumner/Bosque Redondo.

Some Navajo were able to escape the roundups by hiding in canyons and other remote areas. Amazingly they were also able to hide small herds of Churro sheep, a sure-footed and hardy breed that was well-suited to survival in tough environments. After four years as “prisoners of war,” the Diné returned home and began to rebuild both their herds and their Nation. By 1890 the Diné reportedly already had 1.6 million sheep and goats. Between 1870 and 1930, the Diné population quintupled, thanks in part to a protein-rich diet of lamb and mutton. Given that this is the period during which the overall population of Native Americans in the United States reached an all-time low, it was a remarkable achievement.

Sadly this period of rebuilding would lead to more pain and frustration for the Navajo people. When Navajo lands began to show signs of environmental distress, federal agents attributed this to overgrazing, and refused to listen to competing theories of cause. We now know from tree-ring data that the primary factor was climate change: a decades-long dry spell, followed by an unusually wet period. “This dry-then-wet pattern encouraged arroyo erosion and sand-dune formation—a geomorphologic cycle that had happened many times before in this sandstone-dominated landscape.” The huge Navajo herds of goats, sheep, and horses certainly did not help. But what followed was a catalogue of abuse in the name of “the environment.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs instituted a herd reduction program from 1933 through to the mid-1940s. Heavy-handed federal interventions included indiscriminate slaughter of Navajo livestock, and mandated maximum herd sizes, all without adequate compensation. As described in “A Short History on Navajo-Churro Sheep” by Diné be’iiná “Government agents went from Hogan to Hogan, shooting a specified percentage of the sheep in front of their horrified owners, who love their sheep and regard them as family members. First to be shot were the Churro, because the agents thought this hardy breed was ‘scruffy and unfit.’ Today, elders tearfully recall that time and can describe in detail each sheep that was killed and the exact location of the massacre.”

Not surprisingly given the flawed understanding of the causes behind the deterioration, and the draconian way in which herd reduction was implemented, range conditions only worsened, the reservation reached an ecological tipping point, and by the end of the program, to quote historian Jared Farmer, “the tribal economy was in ruins. Unemployment, indebtedness, poverty and alcoholism ravaged Diné Bikéyah.”

The legacy of the US Government’s destructive “reservation” program persists to this day. The Navajo are a nation of 175,000 people in 46,000 households, primarily in the state of Arizona – I quote US not for profit Prosperity Now: “The basic needs of residents within the Navajo Nation are not met: 35% of residents do not have access to running water, 15,000 people do not have electricity and residents must drive for hours in order to reach the nearest hospital or grocery store” – not to mention water supply. Some 35.8% of Navajo households have incomes below the federal poverty threshold, compared to 12.5% for Arizona as a whole. One in two do not have sufficient liquid assets to subsist for three months without income; and they have higher rates of chronic illness, lower life expectancies, and lower rates of insurance than the national average. Less than 9% of the Navajo population over the age of 25 have had the opportunity to access a four-year college degree, compared to 30% for Arizona as a whole, and 16% are unable to find employment, compared to a state average of 5%.

The Navajo remain the resilient and enterprising tribe that rebounded from the horrors of Kit Carson and Bosque Redondo. They have their own grassroots organisations working on providing access to water and solar power. But whilst a handful of non-Navajo have established a niche market for themselves selling Churro meat at a premium price, on the basis that it is leaner and less heavily flavored than the meat of contemporary sheep breeds, the Navajo themselves do not have access to that market. They currently don’t have the necessary infrastructure – from slaughter, cut and wrap to retail – and from an industry standpoint the Churro are totally disrespected. To make shepherding a viable economic proposition for the Diné, the wool must have value as well.

Unfortunately, as outlined in my previous article, US companies like Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger, which have profited considerably from Native American iconography and so ought to constitute an automatic and premium market for Navajo wool, are members of the SAC. And, as we can see from the MII screenshot at the beginning of this article, the SAC claims that virgin wool is unsustainable. These days, like many old European and North African wools, Churro wool sells for cents per pound, if at all. The Navajo produce fine wool in quantity as well, but with a limited market. Clearly what is lacking here is investment. If PVH and Ralph Lauren are serious about sustainability as a production strategy rather than just a marketing exercise, the appropriate course of action is obvious.