Creating a Conversation for a New Era of Design

By Amy DuFault and Sarah Kelley

Effective collaboration between fibersheds and fashion brands is essential for both parties. In early 2020, as the pandemic started to take root, global textile supply chains started to break apart. Large U.S. brands sourcing from other countries saw a major disruption in goods getting to them on time, and they saw how volatile the market was while in lockdown.

While large fashion brands with external links struggled, local economies began to take root. Fibersheds prioritizing regenerative practices, transparency and traceability, and socially responsible were positioned for growth in a society that values the benefits of local.

Fibersheds nationwide are advancing this new approach to textile supply chains. This article hones in on three examples of Fibersheds doing this work and shares key lessons about rebuilding U.S. fiber infrastructure. With more brands coming to fibersheds, both parties need to understand where the other is coming from and work to build alliances with more than just a handshake.

Read on for three stories from Fibershed Affiliates and download the toolkit to learn more. Interested stories from brands about fibershed collaborations? Check out these case studies.

The Southeastern New England Fibershed + Gamine’s Wool Work Vest

In this case, the Southeastern New England Fibershed served mostly as a connector. The supply chain needs for the brand included: wool, processing, spinning, weaving, cut and sew.

Gamine is a Tiverton, RI-based apparel company, founded by gardener and nurserywoman Taylor Johnston. Taylor started Gamine with the goal of supporting and celebrating the processes and traditions of American-made work clothing. From the first pair of selvedge dungarees Taylor made, Gamine has amassed a global following and become known for archival-inspired designs and transparent production processes.

As part of her design process, Taylor often creates garments that she wishes she had for all her gardening and nursery work. Taking inspiration from Rhode Island-based Brown’s Beach Cloth, she contacted the Southeastern New England Fibershed to see if they could collaborate to create a regional supply chain to make a regionally-sourced vest.

“I’ve had this long-standing interest in making things that are no longer made here [domestically] with workwear clothing, and the idea of a vest was floating around in my head for a while,” says Taylor, who is also an active member of the Southeastern New England Fibershed.

Production weaver and textile historian Peggy Hart, who collaborated to put the supply chain together as well as wove the fabric to make the vest, says, “I think what’s really cool about this project is that this original product, the Brown’s Beach Vest, was a Rhode Island-made item that was sold around the country to people, but it was fairly local in how it operated. They took advantage of the reprocessed wool floating around Massachusetts and Rhode Island and incorporated it into the garment to cut costs. I like the full circle piece of this and Taylor trying to do this in Rhode Island to begin with.”

When the group first started out, they knew there was regional wool that could potentially make a small run of vests, but where? And also, because there isn’t any small-scale scouring and spinning in the area, where to do that? “Having been buying wool and having wool processed for the past 30 years, I know who to go to in the area, which is great for these local fibersheds. It’s helpful that I know who to work with and know so many sheep farmers because I go to a lot of wool shows,” says Peggy, whose valuable knowledge of the New England landscape helped Taylor locate 60 pounds of Dorset wool from the University of Rhode Island (URI).

With the URI wool purchased by Taylor, Peggy took it to be processed and spun at Green Mountain Spinnery in Putney, Vermont.

“One thing I’ve learned is when you go to get yarn spun, some mills are better than others at spinning specific types of yarn. Don’t ask a mill to do something they’re not familiar with. Most of these people have learned from trial and error and experience. Most of the people that set up mini mills are not spinners. It’s a pretty steep learning curve to create a yarn that’s usable,” says Peggy.

“I’ve had a number of unfortunate experiences with wool being spun,” adds Peggy, who advises that if possible, have the mills describe what they are best at and also the weights of the yarns they are spinning. Most mills are able to make a two-ply worsted weight, but someone who needs fine wool won’t even go there. “The weaver can’t do anything with the yarn unless it’s spun well,” adds Peggy.

Taylor says she and Peggy have worked together truly symbiotically to have a synergy of ideas and skills that feels incredibly special.

After the cloth was woven by Peggy, it went on to a production sewer who followed Taylor’s pattern and made it into a vest.

And then there’s the cost.

Peggy says, “What’s interesting about the Brown’s Beach Vest is that it has three different yarns, and I’m always trying to figure out how to make things as affordable as possible. So I ran it by Taylor—could we make the weft all local and then just source the warp yarns … so half local? I always tell people to start with your market and how many and how much and work backwards from there. So saying it’s all going to be custom work and as close to the original—I would advise not starting there because it’s expensive and people really needing a work vest won’t be able to afford it.”

But Taylor, who knows her customer well, comes at the price point from a different angle. “Yes it has to be functional, and I want to make sure it’s a piece I can personally wear and have it be functional and practical, but I think cost is a really interesting consideration for Gamine because our customers have resources and would want to support someone like Peggy and be good to the environment.”

Ultimately I don’t think our customers are hoping to have buttons and snaps hand hammered in my friend’s barn, but as local as we can and nothing is perfect,” says Taylor. “I’m a gardener, and it takes at least 10 years to see progress.”

The Acadiana Fibershed— How to Keep Your Fibershed Foundation Story Intact

The Acadiana Fibershed is dedicated to preserving the Acadian Brown Cotton heirloom seed and donates a portion of all cotton seed grown to the University of Louisiana, Lafayette, Cade Farm Seed Bank. They work with farmers who are committed to responsible growing, pursuing organic certification, and adhering to the requirements of the State Department of Agriculture and Forestry, Boll Weevil Eradication Commission.

The Acadiana Fibershed is also preserving the past and creating the future of Southwest Louisiana through efforts to develop a supply chain that will support a sustainable fashion industry within the French-speaking parishes of Southwest Louisiana.

Currently, their fibershed encompasses 22 parishes in Southwest Louisiana. The area’s name recognizes the region’s historic role as the area in which approximately 3,000 Acadian refugees sought sanctuary after being exiled from present-day Nova Scotia in the early 18th century.

The time-honored traditions of family, self-sufficiency, and economic reciprocity remain intact to this day, along with the cultivation of Acadian Brown Cotton. The natural brown cotton was used by the early settlers to weave dowry textiles for Cajun brides referred to as L’amour de Maman—a mother’s labor of love.

With all that work, why on earth would they ever give their cotton seed to an organization known for genetically modifying seeds?

Co-Founder of the Acadiana Fibershed Sharon Donnan says when Company X, a large processing company, started courting her and the team over processing their cotton, they were so excited—but then they had to take a big step back.

“What we encountered was a company only working with genetically modified seed, and when my farmers heard this and realized there was a big connection to the largest chemical producer in the world, it was adios.”

Even though Company X would only be spinning their cotton, the company was very clear that they also wanted to plant that same brown cotton around the facility and neighboring farms to tell a deeper, regional story. Unfortunately, the story wasn’t theirs to tell, and the Acadiana Fibershed realized it was just part of a marketing ploy.

“One of our farmers deeply involved in regenerative agriculture filled me in on the company and warned we should always dig below the surface,” says Sharon, adding that Acadiana Fibershed team member and farmer Bruno Sagrera said, “don’t work anywhere close to that road they’re on.” With their heritage seed so close to the genetically modified seed of Company X, there could be genetic contamination of their cotton strain.

“I think if we were to work with a brand, there would have to be a partnership where our story stays ours, and Acadiana is not exploited, because that’s what’s happened over and over. If there’s a brand that could do something like that for us and not ask us to lose our identity and give it up or sell it, we would be a lot more interested.” – Sharon Donnan

For now, the team is getting trained on how to run a mini mill and is trying to get funding from the state.

“We know what we’re doing, we have a budget, now we need funding to be in control and do our own processing and spinning,” says Sharon. Though the team is walking that fine artisan line where handmade and mechanized meet, the desire to transform local industry is strong.

“This experiment for me has been about breaking molds right and left. I’m not going to say there isn’t a possibility out there where we really increase our yield of cotton, I just know that right now it’s all about baby steps, no need to go faster,” says Sharon.

New York Textile Lab Fibershed — Decentralizing Supply Chains to Grow Regional Economies

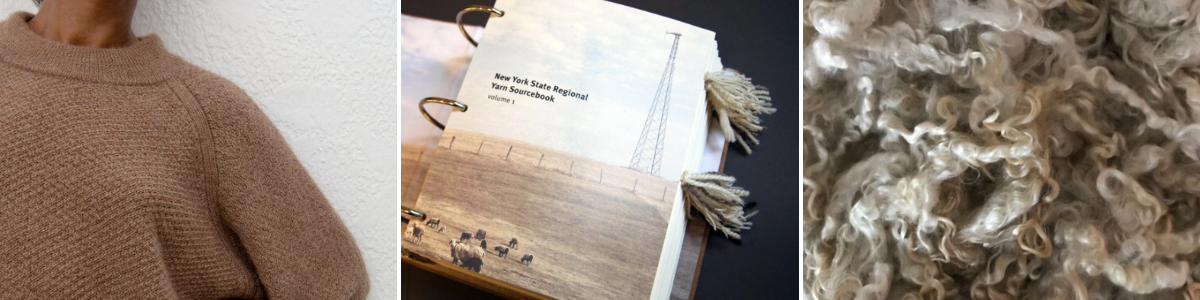

New York (NY) Textile Lab is a design and consulting company that designs yarns and textiles that connect designers to fiber producers and mills to help grow an economically diverse textile supply ecosystem. It’s also the fibershed currently serving New York City. The resources they provide give designers agency to make better decisions about their social and environmental investments. Their textiles embody deep value through unique sourcing and production practices. The fibers offered through the NY Textile Lab, and which are also included in The New York Regional Yarn Sourcebook, are grown on healthy, climate beneficial soil. Founder Laura Sansone partners with mills and manufacturers that are local, transparent, and ethical.

NY Textile Lab believes that the world’s textile production should grow out of abundant, regenerative systems that emerge from collective thinking, rather than centralized systems that rely on extraction, scarcity, and competition. “My main objective is to build a decentralized supply network and I would love to see more mill facilities and more participants to build that kind of economy,” says Laura. “Why not start in a way that creates more economic diversity? Capitalism tends to centralize so I like to offer an opportunity to grow in a different way.”

Laura is fluent in talking about the shift away from fibers reliant on petrochemicals and big agricultural systems. She envisions biodegradable materials like wool and other natural fibers cultivated on smaller farms to bring benefits including better farming practices that have regenerative outcomes, reduced consumption of resources, and a focus on local jobs. These strategies bring both environmental and economic diversity and better stewardship to the planet.

“Ultimately what I envision is a world where designers make their own yarn, and they have a person-to-person connection with the farms and the mills for a truly distributed network. I see it as a person-to-person connection enabling trust in the supply chain akin to Blockchain,” says Laura, who is currently working on an app to facilitate these connections as a next step for her New York Regional Yarn Sourcebook. Laura says we need to make visible these better behaviors and use tech as a way to illuminate reputational currency. “It’s hard to keep trust in the equation without having a tool to foster that.”

Another area where Laura sees a way to create deeper value is to be thinking and educating beyond the price. Some of the pathways she sees to highlight the climate beneficial and regenerative pieces and ethics questions lead through circular design and deeper reflections on nature: “We have to start looking at nature and our agrarian systems as a guide and as inspiration for designers and makers. Why are we following market systems and not natural systems?”

Through the NY Textile Lab’s Carbon Farm Network, a group of fiber producers who use climate beneficial practices on their farms and climate conscious textile and clothing designers who develop yarns and textile products from carbon farmed fibers are co-existing.

The Carbon Farm Plans that are developed for Laura’s partnering farms are reviewed and administered by the Carbon Farm Network’s Agricultural Planner. The fiber is verified Climate Beneficial™ through the Fibershed Affiliate Program. NY Textile Lab is excited to be connecting designers to Climate Beneficial™ materials that have the potential to sequester carbon for the benefit of our climate.

As designers become more aware of the significance of their designs, they have to lock into which story resonates most with them and tell it. Is it water or energy efficiency? Carbon footprint? Human rights? They need to be able to then discuss with their buyers why something is the price it is and get the story supported. “Buyers have to be made aware of capacities and limitations as well as impact,” says Laura

“We’re designers and we problem solve. That’s just what we do.”